Bill Viola/Michelangelo: Life Death Rebirth, Royal Academy review - empty rhetoric versus focused intensity | reviews, news & interviews

Bill Viola/Michelangelo: Life Death Rebirth, Royal Academy review - empty rhetoric versus focused intensity

Bill Viola/Michelangelo: Life Death Rebirth, Royal Academy review - empty rhetoric versus focused intensity

An American video artist meets an old master

Its a preposterous act of hubris, isn’t it? Pairing large scale video installations by American artist Bill Viola with drawings by Michelangelo can’t possibly illuminate our experience of either art form; or can it?

Both propositions are stupid and unhelpful and the idea of trying to update Michelangelo or big up Viola is distasteful. Yet despite these reservations, the juxtaposition is interesting, mainly because it highlights the limitations in Viola’s work and the shortcomings in so much of our thinking.

Bill Viola is a showman, seducing us with visual spectacle. In his hands, video has been upgraded from a humble recording device to a medium capable of addressing big ideas, or that’s the plan. To this end he embraces the production values of Hollywood and high end advertising to make large screen installations that are awesomely engrossing. Shot in real time, the footage is slowed down to give it more visceral impact and depth of feeling; ironically, though, the slicker and more visually impressive the results, the shallower the message seems to be and the faster the impression fades.

Take Tristan’s Ascension (Pictured right) for example. Made in 2005 for a production of Wagner’s opera Tristan and Isolde, the video opens with a corpse lying on a slab bathed in cold light, an image of total desolation in death. Droplets of water begin to fall and bubbles to rise; both increase in speed and volume until a deluge of water pounds the inert body while, at the same time, a raging torrent surges upwards. Under the onslaught, the corpse begins to twist and turn, and finally lifts off the slab to rise into the ether with the bubbles. The ascension is euphoric, yet somehow hollow. Immediately it is over you start wondering about the technical wizardry used to produce the effects.

Take Tristan’s Ascension (Pictured right) for example. Made in 2005 for a production of Wagner’s opera Tristan and Isolde, the video opens with a corpse lying on a slab bathed in cold light, an image of total desolation in death. Droplets of water begin to fall and bubbles to rise; both increase in speed and volume until a deluge of water pounds the inert body while, at the same time, a raging torrent surges upwards. Under the onslaught, the corpse begins to twist and turn, and finally lifts off the slab to rise into the ether with the bubbles. The ascension is euphoric, yet somehow hollow. Immediately it is over you start wondering about the technical wizardry used to produce the effects.

The downward torrent appears actual enough, (the actor really is getting wet) while the upward rush of water must be footage of a waterfall inverted and superimposed; and you can almost see the strings that lift the lifeless body. Viola’s message, that an afterlife awaits us, is subverted by the very means he employs to convey it. We are too canny to be duped by soothing stories and clever digital manipulation. In this era of fake news, scepticism reigns.

Tristan’s Ascension is coupled with two drawings by Michelangelo from 1532 of Christ rising from the dead. Risen Christ (Pictured below left) from the Queen’s Collection shows Jesus stepping out of the grave. Pushing aside the lid of the tomb with his foot, he propels himself upwards with a surge of energy. A swirl of drapery enhances the momentum of this dynamic assertion of life. Whether we believe in the actuality of the resurrection is neither here nor there; the power of the image comes from the concentration and mastery of its conception. In its subtlety and intensity, the drawing emanates conviction. The medium is the message, as Marshall Mcluhan famously said.

The fulcrum of the exhibition is Viola’s Man Searching for Immortality/Woman Searching for Eternity 2013. Projected onto slabs of polished black granite resembling tombstones are a naked man and woman. Each uses a torch to examine their ageing body; but while trying to locate the soul or some other transcendent element, they reveal nothing more than the inexorable decline of their withering flesh. Condemned to death, as we all are, their plight seems insuperable. Viola labours the point that without belief in an afterlife, we are doomed. Lack of belief, though, is precisely the problem that vitiates the work and empties it of affect. No matter how sophisticated the presentation, ultimately the message feels hollow, like bluster.

The fulcrum of the exhibition is Viola’s Man Searching for Immortality/Woman Searching for Eternity 2013. Projected onto slabs of polished black granite resembling tombstones are a naked man and woman. Each uses a torch to examine their ageing body; but while trying to locate the soul or some other transcendent element, they reveal nothing more than the inexorable decline of their withering flesh. Condemned to death, as we all are, their plight seems insuperable. Viola labours the point that without belief in an afterlife, we are doomed. Lack of belief, though, is precisely the problem that vitiates the work and empties it of affect. No matter how sophisticated the presentation, ultimately the message feels hollow, like bluster.

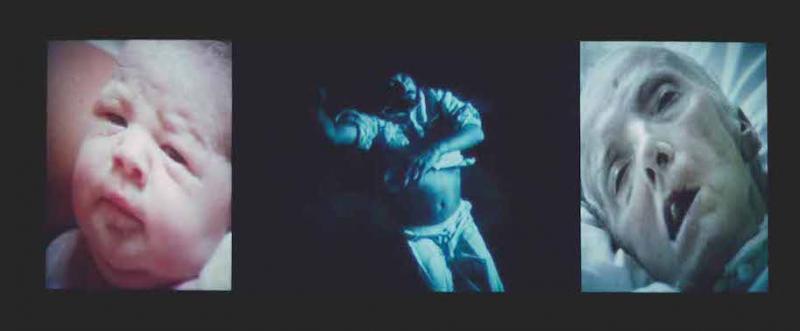

The exhibition offers a retrospective of Viola’s work and the most compelling piece is one of the earlier ones, which relies less on visual pazazz. Nantes Triptych, 1992 (Main picture) addresses a grand theme – the span of human life – but does so simply and directly without fancy lighting, dramatic effects or heavy-handed metaphor. On the left hand screen we see the artists’s wife giving birth. Perching on the end of a bed in the supporting arms of her husband, she groans and cries out as the painful process unfolds with mundane actuality in real time. When the infant finally emerges, the relief is palpable; one wants to whoop with joy. Meanwhile, on the right hand screen, Viola’s mother lies motionless in a hospital bed, dying; the only sound in this sterile environment is the rasping gurgle of her respirator. On the centre screen, a man lies suspended in water, floating between the twin poles of life and death, as it were, until he is swallowed up into blackness. But the staged drama of this central image can’t hope to compete with the visceral power of the unadorned reality that unfolds on either side.

Hung opposite Nantes Triptych are Michelangelo’s Taddei Tondo,1504-5 and drawings of the Virgin and child. Compared with the messiness of birth as captured by Viola, they seem to epitomise unruffled calm, yet a chill note intrudes. The infant Jesus sits on his mother’s knee, his arms round her neck in a gesture of extreme tenderness; but standing to Mary’s right is St. John the Baptist carrying a cross to remind us of the crucifixion. He features again in the “Tondo” holding a goldfinch whose red plumage symbolises the shedding of Christ’s blood on the cross.

The theme of death in life is reversed in the drawing The Lamentation of Christ,1533-4 (pictured right). Mary sits cross legged with one knee raised to support the lifeless body of her dead son who lies in the bowl of her lap, cradled between her thighs. This intimate configuration serves as a reminder that he was born from her body. The cycle of life and death is also evoked through the composition. One’s eye roams restlessly over the limbs of the living and the dead, which are intertwined; Christ’s hand rests on Mary’s shoulder, for instance, while her hand nestles under his armpit. There is no finale, only an endless circularity.

The theme of death in life is reversed in the drawing The Lamentation of Christ,1533-4 (pictured right). Mary sits cross legged with one knee raised to support the lifeless body of her dead son who lies in the bowl of her lap, cradled between her thighs. This intimate configuration serves as a reminder that he was born from her body. The cycle of life and death is also evoked through the composition. One’s eye roams restlessly over the limbs of the living and the dead, which are intertwined; Christ’s hand rests on Mary’s shoulder, for instance, while her hand nestles under his armpit. There is no finale, only an endless circularity.

Michelangelo conveys his message with subtlety and restraint so that exploring every detail is endlessly rewarding. Viola’s increasing reliance on impressive visual effects, on the other hand, makes for stunningly beautiful installations that, ultimately, leave you feeling empty. The contrast couldn’t be clearer.

- Bill Viola/Michelangelo: Life, Death, Rebirth at the Royal Academy until 31 March

- Read more visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Add comment