'Of course art doesn't change the world': Situationist artist Jacqueline de Jong on violence, eroticism and the importance of humour | reviews, news & interviews

'Of course art doesn't change the world': Situationist artist Jacqueline de Jong on violence, eroticism and the importance of humour

'Of course art doesn't change the world': Situationist artist Jacqueline de Jong on violence, eroticism and the importance of humour

The Dutch veteran's first UK retrospective has opened at MOSTYN in Wales

Jacqueline de Jong doesn’t want to talk politics. But this should have been foreseeable. After all, she has travelled to Mostyn, in Llandudno, for her first solo exhibition in a UK art institution. And this is a painting show, not a political rally.

The works span six decades of art creation right up to the present. So it’s not a snapshot of that revolutionary decade, the 1960s, which she spent in Paris, in and out of the Situationist International, editing the fabled Situationist Times.

It’s understandable she doesn’t want to rehash all that. But I only realise this just prior to our interview, and I admit, as a result, De Jong has me on the back foot.

“Why choose painting over politics?” I ask, nervously folding away my planned questions.

“Why I chose painting over politics?” she repeats with incredulity. “Should I have done politics? Why do you think I should have chosen politics?”

We are sat at a corner table in the gallery café. At just over 80 years of age, De Jong is both lively and grand, with a history not to be trifled with. As a child, the French Resistance saved her from internment by the Nazi party. As a young woman, she became the companion of Danish painter Asger Jorn. Around this time, she joined hardline agitators, the Situationist International, whose artists drew inspiration from surrealist painting and Marxist theory; she was to leave in solidarity with a group of expelled German artists. In May ‘68 she went to the barricades. And she has continued to make art throughout the rest of the history we were told had come to an end with the fall of the Berlin Wall.

But she definitely does not want to talk politics: “Why should I have chosen politics? Because I was a Situationist?”

A single poor question from me has generated five rapid counter-questions from her. Six if you count the quite reasonable, but also accusatory aside: “Are you vaxxed?”.

Eventually she concedes art might be effective in some ways theory is not. “I think art might change the world if it’s considered more than it is,” she says doubtfully, before doubling down on futility with yet another question for me: “Of course, it doesn’t change the world, but why do people make art?”

While her show cannot answer this question, it will certainly change your stay in this genteel seaside town. De Jong works series by series and almost a dozen phases from her expansive career feature here, in clusters of two or three works. These are by turns expressive and realist, and poppy. In some scenes her paint is laid on dark, heavy and thick. Elsewhere it is applied rapidly and in many places her off-white canvas is bare. At times colours are bright and cheerful, forms crisp. At times, she will tell stories, as in her Série Noire, at others she can be comical and kitchen sink, as her paintings of billiard games and billiard cues ably show.

There are also vitrines dedicated to several venerable issues of The Situationist Times, an artistic foray into agitprop, edited and published by De Jong between 1962 and 1964. As tangible evidence of the optimism and potential for change embodied by the Sixties, these still look vital, when seen behind glass, in the flesh.

Knowing these are in her show I stumble towards a question about May ‘68 and De Jong, challenges me once again: “If that counts specifically for you then it’s your problem, not mine.” Unwisely, I press on. Have we lost the grounds for effecting revolutionary change?

“That’s also your problem. Who says it’s my problem? I mean no, no. Did it affect me at that moment, being optimistic. I have no idea.”

Thankfully De Jong seems by now as amused as she might be annoyed by my questioning and she concedes that, owing to climate change and the internet, we live in a very different world to that in which she began to paint. “I mean you could say in the early Sixties it was only 16 years after World War Two, so people were optimistic,” she offers. “Things were getting better, probably. I don’t know if that’s an answer.”

I assure her it is, and change tack. Given the glut of full colour images in today’s magazines, does painting still have more visual power than photography? De Jong responds at once: “I don’t know. Does it?” It leads me to claim people spend more time considering a painting in a gallery than on a printed page, or even a mobile phone.

“Yeah, yeah, yeah, that’s true,” she agrees. “I don’t know. You’re asking me questions which you could answer.” Then tracking back, she asks me again: “Why do you make this difference between social politics and art?”

I fish around for a question that only De Jong can answer, like how does she decide what to paint, given her range of themes and styles?

“Humour is very important,” she begins. “I mean, the erotic is important. Violence is important. It’s things that are important in life.” She adds a caveat that eroticism is an undercurrent, not overt sexual content.

“Humour is very important,” she reiterates, “I think it’s important in a life as well as in a work.”

There is humour in plentiful evidence, among her paintings in this show. It’s in the billiard player stretching across the baize, seen from a crazy aerial angle in La Carambole Inspiré par un Burin de J. Minne, 1976. It’s in the suited figure climbing a staircase whose cramped posture appears caused by the top of the canvas Big Foot Small Head (for Thomas), 1985 (pictured above right). And it’s in the old-school journo photographing a murder scene with lofty detachment, Gardez Vous à Gauche, 1981.

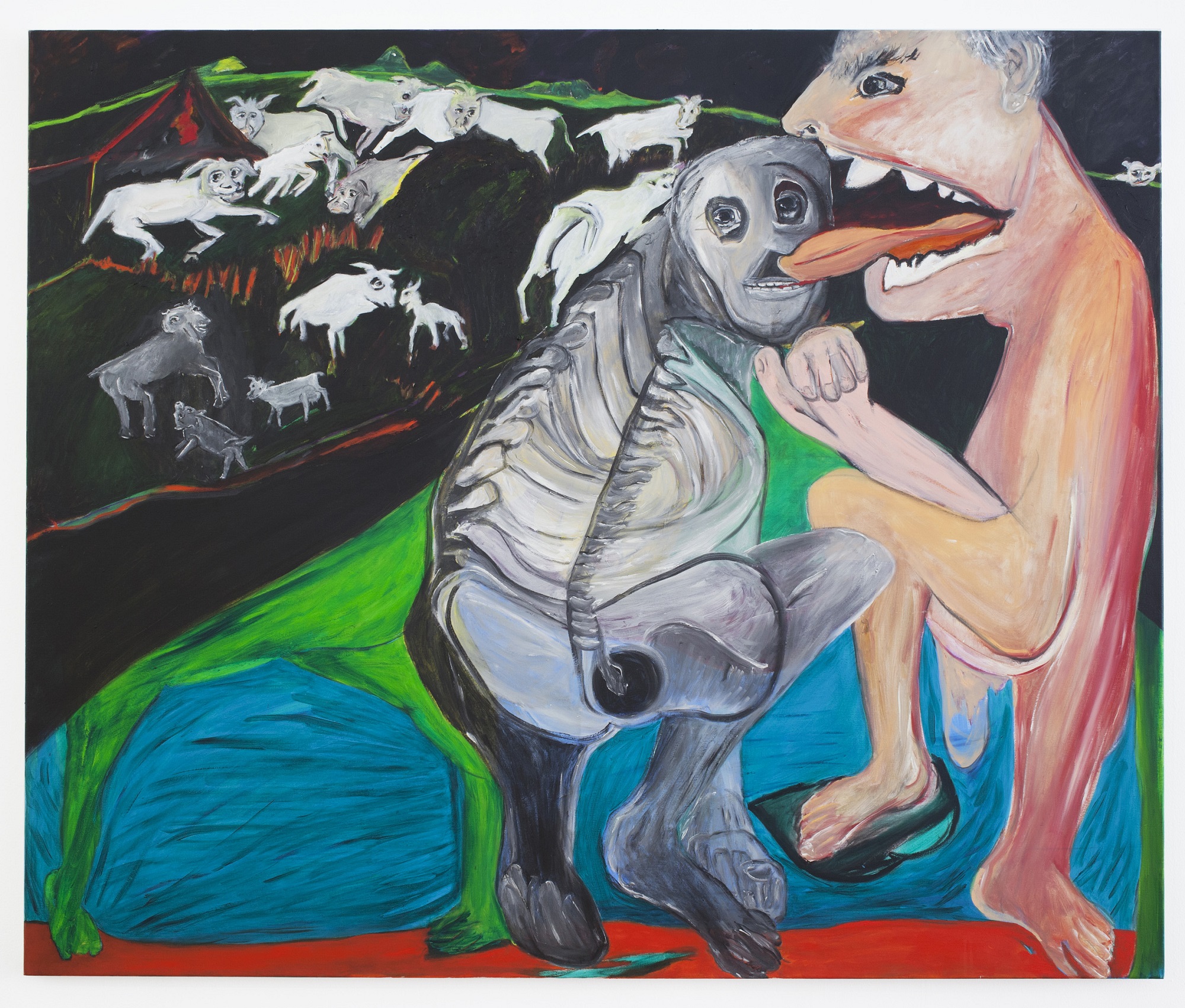

And indeed, violence is central to de Jong’s Series Noire, with each murder victim punctured by a clean stiletto blade. Meanwhile eroticism pervades a show in which tongues, folds of flesh, pelvic bones and bright pink penises make disturbing appearances in jumbled compositions that represent sex as a tumult. Even the show’s title, The Ultimate Kiss, hints at erotic bliss. (Pictured above: The Ultimate Kiss, 2001-12)

But after this ultimate kiss, it is still, despite everything, hoped the show will deepen the viewer’s engagement with painting. “I think I would be extremely happy if it would make people look at art more,” says De Jong. “Perhaps it can trigger an audience to look at other things in a different way. That would make me very happy.”

Nevertheless, foreseeably, De Jong still closes down any suggestion she be a "missionary" for art: “I can’t say people should be going out singing, glorifying art or something like that, at all,” she says, even though this is a glorious show reflecting a glorious life.

“What else can I say?” she asks. It seems only fitting to leave her with the ultimate question.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Add comment