Cornelia Parker invited over 60 fellow artists to join her in exhibiting at the Foundling Museum in London. Titled Found, the show spills out from the basement gallery to infiltrate every room in the building and remind us that, when the Foundling Hospital was set up as a charity for destitute children in 1739, artists made an important contribution.

William Hogarth invited friends to exhibit at and donate work to the hospital while Handel ensured the charity's place in the social calendar by giving benefit concerts there every year. The museum contains some moving exhibits; when consigning their children to the institution, parents often left tokens identifying their little ones and bearing promises to reclaim them when times got better. And the most poignant contributions to Found are those that refer, no matter how obliquely, to this sad history.

A painting by Hogarth is a reminder that homelessness and displacement are nothing newBased on these tokens of love and hope, Vicken Parsons has made three small paintings. Isolated on a neutral ground, a scrap of cloth, a cockade and a blue necklace seem especially forlorn as indicators of loss and longing. Six days after her birth in 1999, Antony Gormley made a cast of his daughter Paloma. Coiled in the foetal position, the infant lies on her stomach on the floor of a bare room, as though abandoned to fate. Although the sculpture is black and made of iron, it is a startling reminder of how vulnerable infants are; luckily this child was born to parents able to care for her.

Hanging on one wall is a year’s worth of pawnbroker tickets threaded onto a string two-and-a-half metres in length. This fascinating item was found by furniture designer Ron Arad, who was particularly drawn to it because the year was 1951, when he was born. Many bear the letters GWR – gold wedding ring – attesting to the hardship experienced by couples struggling to make ends meet, like those who left their hapless infants at the hospital centuries earlier.

Lying on the floor of the splendid Court Room is a dirty sleeping bag apparently occupied by a homeless person. Nomad is actually a bronze cast by Gavin Turk, painted to look as scruffy as those lying in many a London doorway. Its position beneath a painting by Hogarth of Moses Brought Before Pharaoh’s Daughter, 1746, is a reminder that homelessness and displacement are nothing new. Moses was a foundling, set afloat in a makeshift boat by his mother before being rescued from the Nile by Pharaoh’s daughter, Bithia.

Lying on the floor of the splendid Court Room is a dirty sleeping bag apparently occupied by a homeless person. Nomad is actually a bronze cast by Gavin Turk, painted to look as scruffy as those lying in many a London doorway. Its position beneath a painting by Hogarth of Moses Brought Before Pharaoh’s Daughter, 1746, is a reminder that homelessness and displacement are nothing new. Moses was a foundling, set afloat in a makeshift boat by his mother before being rescued from the Nile by Pharaoh’s daughter, Bithia.

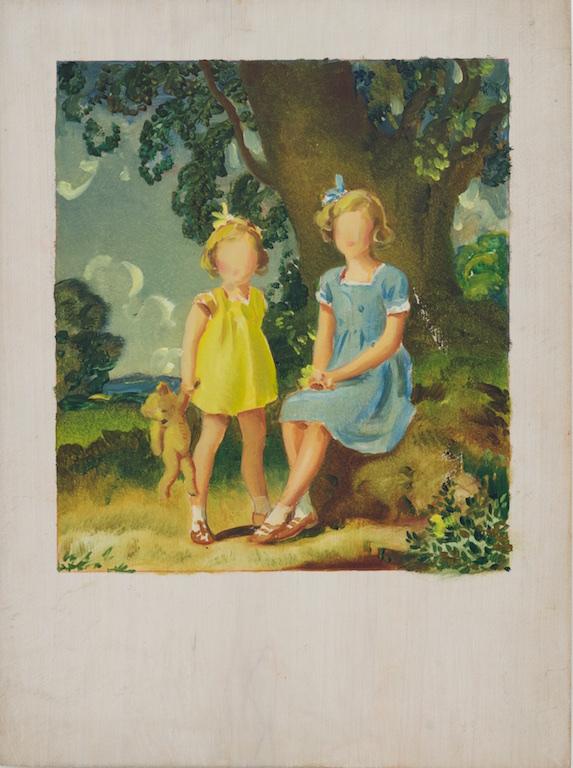

On arrival at the hospital the children were give new names, perhaps as a way of establishing a new beginning untainted by their unfortunate pasts. Among the memorabilia, Cornelia Parker has introduced an unfinished sketch of two young girls by portrait painter Alfred Munnings, former president of the Royal Academy (main picture). With their crisp summer frocks, ribbons and sandals, the sisters clearly come from a comfortable home; but their faces have yet to be painted and, in this context, the blank masks take on sinister connotations. It's as though these luckier girls were also being treated as though they were blank slates – raw material to be moulded into compliant beings.

Life in the hospital was no bed of roses. The children were destined to go into service if they were girls, and the army if they were boys. Discipline was rigorous and a display cabinet contains citations for good behaviour. Secreted among them is a sheet of paper, bought at auction by Jeremy Deller, listing the numerous detentions meted out to John Lennon at his school for crimes such as “not wearing school cap” and “groaning at me”, suggesting that obedience is badly over-rated!

Another cabinet contains two silver-plated spoons belonging to the grandmother of designer, Thomas Heatherwick and titled Seventy Years of Stirring (pictured above right). With their rims worn down by friction, these gravy spoons attest to a life of domesticity spent caring for others. John Smith’s affectionate video of the stick used by his father to stir paint over many decades pays tribute to a lifetime of conscientious DIY activity, which provided the colour scheme for his childhood.

Parker points out that for something to be found it must previously have been lost; David Shrigley takes a light-hearted approach to loss and how we value things we are parted from. Pinned to a tree, a hand-written note asks for information about a grey and white pigeon that has no name or identifying features. Mimicking the signs put up by pet owners desperate for news of lost animals, Shrigley’s wry contribution invites us to question why we lavish affection on some creatures but not others. Finding a dead frog in her cellar, Alison Wilding was struck by the elegance of the dessicated corpse (pictured left). There’s also great beauty in the filigree remains of a First World War helmet found in a loft in Italy and contributed by Heather Ackroyd and Dan Harvey.

Parker points out that for something to be found it must previously have been lost; David Shrigley takes a light-hearted approach to loss and how we value things we are parted from. Pinned to a tree, a hand-written note asks for information about a grey and white pigeon that has no name or identifying features. Mimicking the signs put up by pet owners desperate for news of lost animals, Shrigley’s wry contribution invites us to question why we lavish affection on some creatures but not others. Finding a dead frog in her cellar, Alison Wilding was struck by the elegance of the dessicated corpse (pictured left). There’s also great beauty in the filigree remains of a First World War helmet found in a loft in Italy and contributed by Heather Ackroyd and Dan Harvey.

When Mona Hatoum was in Lebanon visiting her sick mother, she had no access to materials or a studio; she began picking up bits of twisted wire from a building site and, arranged in a display cabinet, these scraps of metal are like found doodles or snatches of elegant writing in a long lost language. Using answerphone messages, composer Jocelyn Pook contemplates failed attempts at communication. “Hello, are you there?” asks the message and “Speak soon, goodbye”, followed by plaintive requests for a response “When you’ve got a spare mo.”

While archaeologists spend their time unearthing fragments and preserving them as vital evidence of our collective history, Christian Marclay records things that have only just been thrown away. Bottle Caps, 2016, is a rapid sequence of stills detailing the colours and shapes of hundreds of discarded bottle tops photographed on his way to and from the studio. Placed near the tokens left by distraught parents on consigning their children to the hospital, his animation creates a sharp contrast between their desire to hang on and our unthinking penchant for chucking things away.

When the staircase was stripped from the Mayfair house where Jimi Hendrix had lived, Cornelia Parker managed to salvage bits of it from a skip. The stairs were being sacrificed to provide public access to Hendrix’s flat. Attached to the walls in the museum basement, the remnants are like religious relics; were they worth preserving, though, or might they have been happily consigned to oblivion?

And how does one value the stuff salvaged by Jessica Voorsanger from Bob Geldof’s rubbish or the garbage that Phyllida Barlow has amalgamated into a noxious looking heap? What and whom we value and how we choose to preserve things while throwing others away is a question that this exhibition asks in many poignant, amusing and thought-provoking ways.

Add comment