Enzo Green, Shirim, Raethro Red, Raemar Magenta. Everything has a name. But beyond the meaningless but musical sounds of their titles, the light projections and installations on view at Houghton Hall by the leading American light, land and skyscape artist James Turrell are an ineffable art whose presence and effect is subtle, substantial, utterly memorable and almost beyond words.

Descriptions, yes, as light projections make the spectator believe that these are solid if translucent slabs and walls, voids and curves, convex, concave, real: the brain and eye respond in innumerable ways, but invariably with feelings of sustained and serene euphoria. Turrell’s art provides almost unimaginable otherworldly trips, playing on perception and painlessly demanding and receiving the most intense visual and mindful attention. And we owe this remarkable grouping of magnificently beautiful light sculptures to the determination of Houghton and its owner to place the 18th-century great neo-Palladian house and estate firmly in the 21st century. Houghton has installed within the great house and in the grounds five decades of Turrell’s work.

Looking to its history, Houghton collaborated with the Hermitage in St Petersburg two years ago to bring back some of the Old Masters sold by descendants of its builder, the first prime minister, Sir Robert Walpole, to Catherine the Great, and to once more (if temporarily) embrace and enhance its exquisite and ornate interiors. And history is behind the notion of patronage, of art at the heart of things. Quietly and adventurously the estate has been commissioning and purchasing outstanding contemporary sculpture for sensitive display throughout the grounds, including a shimmering stone circle by Richard Long, the solidified interior of a small ghostly hut by Rachel Whiteread, and the stainless steel Scholar Rock by the Chinese artist Zhan Wang.

And here, once again, is art that could not be realised without the most up-to-date technology, and yet in its realisation convinces the spectator of its inevitable simplicity. Two site-specific works by Turrell are already in the park, including St Elmo’s Breath (the patron saint of sailors) in an 18th-century water tower. Turrell’s habitual blue shirt bears the legend Light Reigns, also the name of his sailing boat. Raised as a Quaker, he trained early on as a pilot and was an aerial cartographer. He is also an ardent sailor, skimming a light-spangled sea under a limitless sky, yet confining his own work firmly to the land. Thus the wooden structure of Seldom Seen, Skyscape, 2004 (pictured left, photographed by Peter Huggins): a room raised several stories above ground level, reached by a winding woodland path, and up a wooden ramp, has its rectangle open to contemplation of the twilit sky, reinforced by concealed lighting which somehow enhances our sense of barely visible clouds gliding above in the deep cerulean blue. It is almost a reverse of the sea, the air currents above in visible movement marked by stars and clouds.

And here, once again, is art that could not be realised without the most up-to-date technology, and yet in its realisation convinces the spectator of its inevitable simplicity. Two site-specific works by Turrell are already in the park, including St Elmo’s Breath (the patron saint of sailors) in an 18th-century water tower. Turrell’s habitual blue shirt bears the legend Light Reigns, also the name of his sailing boat. Raised as a Quaker, he trained early on as a pilot and was an aerial cartographer. He is also an ardent sailor, skimming a light-spangled sea under a limitless sky, yet confining his own work firmly to the land. Thus the wooden structure of Seldom Seen, Skyscape, 2004 (pictured left, photographed by Peter Huggins): a room raised several stories above ground level, reached by a winding woodland path, and up a wooden ramp, has its rectangle open to contemplation of the twilit sky, reinforced by concealed lighting which somehow enhances our sense of barely visible clouds gliding above in the deep cerulean blue. It is almost a reverse of the sea, the air currents above in visible movement marked by stars and clouds.

Within the house are prints, holograms and light installations. Some models and drawings are on view for his huge, soon to be completed sculpture, moulding an extinct volcano in Arizona, Roden Crater. It's emblematic of the scope of Turrell’s ambition and determination. The crater, the equivalent of some 14 stories high, rising out of the flat Southwest scrubland, is one of the most breathtaking art-into-nature, nature-into-art projects yet attempted.

Among other near miraculous engineering feats of discreet intervention, the crater hosts 900ft tunnels (18ft in diameter). It will eventually achieve its aim, already clearly in view, as a kind of celestial observatory, created by many a scientific and engineering base, yet definitely beyond the logical and into the realm of the ethereal. It is not an irrelevance that visualisations for Roden Crater are present at Houghton, suggestive of the life-long engagement that Turrell has had with pragmatic solutions to the most vaulting of hopes for the engagement of art with life.

Discrete light installations in dedicated spaces play with notions of perception and deception. They make us apprehend a wall of projected light as a solid substance. The innumerable subtle changes of coloured light calm our agitation, soothe us into observation, and provide experiences of almost uniquely quiet and serene euphoria, somehow uniting our notions of light and space with a sense of our own physical presence, both firmly earthbound yet inhabiting an otherworldly realm.

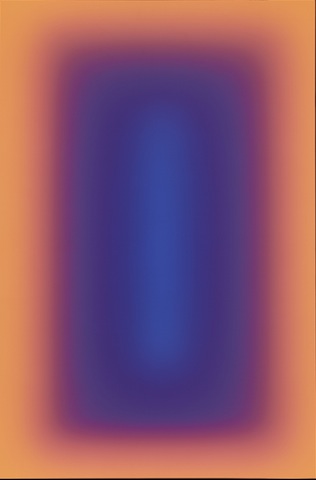

Turrell's medium is light, and he does not abandon technology for a false reliance on the wholly natural in the 21st century. Shirim, 2015 (pictured right, photographed by Peter Huggins), is a tall rectangular piece in a room of its own, continually changing colours in a rectangle within a rectangle of light: as a spectator you are so immersed that it's as though you are being completely bathed in light. Thoughout Turrell’s work the effects are of an ardent simplicity, an inevitable yet surprising sequence of colours melding one into another, yet behind it is a complex mix of artificial and natural light, of programming and technical innovation.

Turrell's medium is light, and he does not abandon technology for a false reliance on the wholly natural in the 21st century. Shirim, 2015 (pictured right, photographed by Peter Huggins), is a tall rectangular piece in a room of its own, continually changing colours in a rectangle within a rectangle of light: as a spectator you are so immersed that it's as though you are being completely bathed in light. Thoughout Turrell’s work the effects are of an ardent simplicity, an inevitable yet surprising sequence of colours melding one into another, yet behind it is a complex mix of artificial and natural light, of programming and technical innovation.

At dusk, the site-specific lighting of the west façade of Houghton begins (main picture), an hour perhaps of changing light illuminating porticos, pediments, statues, windows, the delineation and details that make of the house something beyond its immovable presence. Throughout the darkening night, colours move across a spectrum of oranges, pinks, roses, blues, aquamarines, greens and whites. Solidity fades as we are reminded that nothing is the same, except for the immutable rule that everything changes. A profound beauty bears Turrell’s message of inescapable mortality.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment