Entry to Mike Nelson’s Hayward Gallery exhibition is through what feels like the store room of a reclamation yard. Row upon row of Dexion shelving is piled high with salvaged building materials including old doors, ancient floorboards and wrought iron gates, while even more gates and doors are leant against the walls.

It’s all a bit too neat and tidy for a real junk yard, though; and my heart sank. Please don’t let this retrospective be a sanitised version of Nelson’s installations, because without the right degree of tackiness, they simply wouldn’t work. I needn’t have worried, though; from here on everything is pitch perfect.

The main downstairs gallery has been turned into a warren of narrow corridors leading to dozens of seedy little rooms, each one a convincing recreation of a run-down joint in some remote backwater. Step inside The Deliverance and The Patience and you could be in any down-at-heal establishment in Brixton, Whitechapel, Preston, Casablanca, Cairo or Cape Town.

Kimja Travel is advertising flights to Lagos and Nairobi, but the telephone on the desk hasn’t rung in years and the Wanderlust magazine left in the scruffy reception area dates back to May 1930. Every detail is telling – from the map of the world to the Air France posters, the dirty car seats, green rubber floor matting and defunct ceiling fan.

Kimja Travel is advertising flights to Lagos and Nairobi, but the telephone on the desk hasn’t rung in years and the Wanderlust magazine left in the scruffy reception area dates back to May 1930. Every detail is telling – from the map of the world to the Air France posters, the dirty car seats, green rubber floor matting and defunct ceiling fan.

Nelson is obsessed with detail, and each space has an equally distinctive flavour. Everything has seen better days. Two filthy sleeping bags lie crumpled in a room devoid of furniture except for a couple of camp beds, a rotting chair and a battered old dustbin. The clock has stopped in an abandoned garment factory where workers had to squat on low benches to cut the fabric.

Ahmed has carved his name in the battered casing of an old lathe that must have been ripped out in a hurry, since the fan has been left on to whir away the time. The carpets on the floor of the prayer room could do with a good clean and most of the walls have had the plasterboard torn off.

In a room used by some arcane cult, the walls are painted purple (pictured above right). There’s an altar littered with skulls, animal horns, Nefertiti heads, a seated Buddha and a VHS of Indian guru Sathya Sai Baba holding forth. Lining the walls of the Sea Captain’s club in Hong Kong (pictured below left) are paintings of schooners, while attached to the bar are signs reading “Please Do Not Spit”.

It’s all very spooky, yet strangely familiar – partly because each room is so plausible, partly because these are the kinds of places you might have come across on your travels and partly because the artist is a dab hand not just at recycling found materials but also his own creations. First built for the Venice Biennale of 2001, The Deliverance and The Patience, for instance, echoes even earlier iterations at Matt’s Gallery when it was in Mile End.

If you climb the stairs in a room dedicated to a dodgy parliamentary election, you get a bird’s eye view of the structure you’ve just been wandering through. It’s like peering into someone’s attic where their unwanted bric a brac is stashed; the space is cluttered with old chairs, defunct TVs, a model boat and even a cage for homing pigeons. This is the stuff that didn’t make it into this installation, but might be used in the next one. Nothing gets wasted; the materials stored on the shelves of that first room, for instance, are the dismantled remains of Nelson’s Venice Biennale installation of 2011.

If you climb the stairs in a room dedicated to a dodgy parliamentary election, you get a bird’s eye view of the structure you’ve just been wandering through. It’s like peering into someone’s attic where their unwanted bric a brac is stashed; the space is cluttered with old chairs, defunct TVs, a model boat and even a cage for homing pigeons. This is the stuff that didn’t make it into this installation, but might be used in the next one. Nothing gets wasted; the materials stored on the shelves of that first room, for instance, are the dismantled remains of Nelson’s Venice Biennale installation of 2011.

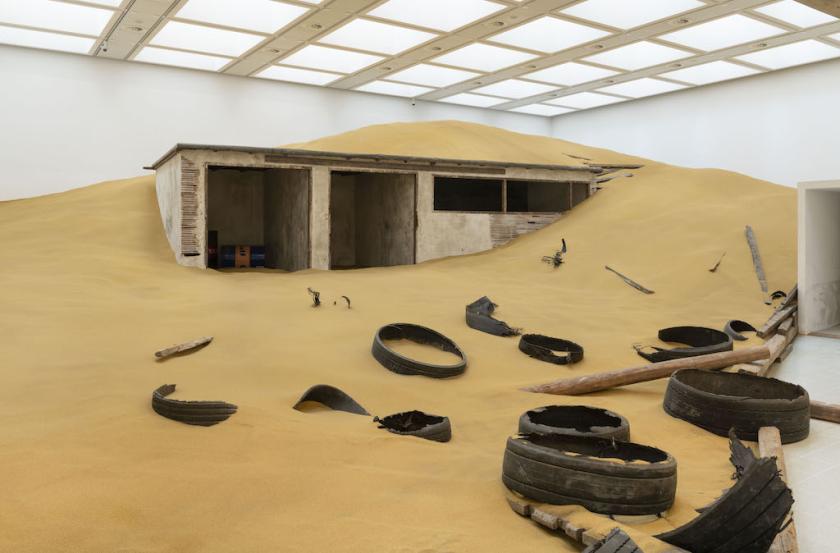

Everything, it seems, including art, is provisional, subject to change and dissolution. Nothing brings this home more clearly than Triple Bluff Canyon (the woodshed), 2004 (main picture) which fills the upstairs gallery. A derelict building lies half-buried by a mountain of sand littered with blown-out lorry tyres (main picture: M25, 2023). Walk into the bunker-like space underneath the dune, and you find a darkroom hung with photographs of Nelson installing an earlier version of the piece.

Another gallery is dedicated to industries that once flourished in Britain. Old machines like a bobbin sander, surface grinder and thresher (pictured below: The Asset Strippers (solstice), 2019) are placed on plinths made from old filing cabinets or industrial materials – elevated to the level of public sculptures, as though in honour of the working man. Back downstairs, the artist has created a facsimile of his own studio – the front room of a Victorian terraced house filled with clobber. It overlooks a weird work-in-progress comprising a multitude of concrete heads impaled on a grid of steel reinforcing rods; and as though to stress that producing art is hard work, in the middle is the mixer in which the concrete was made and the workbench on which the rubber moulds of the heads were filled.

Back downstairs, the artist has created a facsimile of his own studio – the front room of a Victorian terraced house filled with clobber. It overlooks a weird work-in-progress comprising a multitude of concrete heads impaled on a grid of steel reinforcing rods; and as though to stress that producing art is hard work, in the middle is the mixer in which the concrete was made and the workbench on which the rubber moulds of the heads were filled.

Given that the exhibition is called "Extinction Beckons", you might expect the overall tone to be apocalyptic, filled with warnings of impending doom. Yet despite his embrace of entropy, Mike Nelson's work strikes me as touchingly nostalgic – harking back to the days when manual labour was valued and art was made by real men.

- Mike Nelson: Extinction Beckons at the Hayward Gallery until 7 May

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment