Extract: Peter Brook - Tip of the Tongue: Reflections on Language and Meaning | reviews, news & interviews

Extract: Peter Brook - Tip of the Tongue: Reflections on Language and Meaning

Extract: Peter Brook - Tip of the Tongue: Reflections on Language and Meaning

The wisdom of a great theatre-maker: on Shakespeare and the 'empty space', and thinking between English and French

A long time ago when I was very young, a voice hidden deep within me whispered, "Don’t take anything for granted. Go and see for yourself." This little nagging murmur has led me to so many journeys, so many explorations, trying to live together multiple lives, from the sublime to the ridiculous.

But what are levels, what is quality? What is shallow, what is deep? What changes, what always stays still?

This can now lead us together through many forms, at many times, in many places. To begin with, what is a word?

This can now lead us together through many forms, at many times, in many places. To begin with, what is a word?

If we say to a child, “Be good”, the word “good” has its everyday commonplace meaning. If we rise above the ground level, the word “good” brings us to finer and finer shades of goodness. Even more so in French – Soyez sage, the parents say to their children, using sage, a word for wisdom. There are so many words that contain such promises. A “divine” evening. “Divine” belongs to the sky. To use “divine” casually makes the “sacred” lose all its meaning.

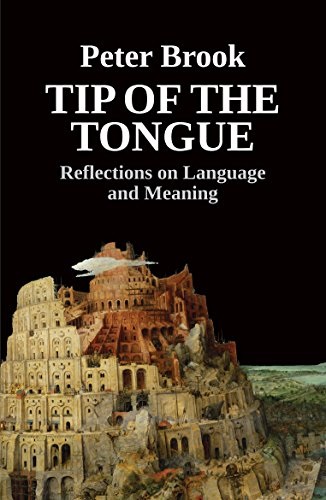

In the pages of my new book Tip of the Tongue: Reflections on Language and Meaning, we explore together the sometimes comic and often subtle differences between two languages that have lived together for so long – French and English.

With William the Conqueror, the Latin-based language penetrated into English and vastly enriched its vocabulary. For us, the Norman invasion was a blessing. On the other hand, the Anglo-Saxon idiom seemingly never penetrated beyond Agincourt. Thanks to this, French, with a much smaller vocabulary, became a vehicle for pure and crystal-clear thought. I must, however, warn any prospective reader that all comments on the French language in the book come necessarily from an Anglo-Saxon point of view.

After nearly half a century of living in France, when I ask for something, clearly, in a shop, the person serving me winces and immediately answers me in English. Either it is fear of not understanding the foreigner or else the pain of hearing their fine language mangled, its precise rules ignored. This has been a starting point for relishing the difference between two languages which are like chalk and cheese.

Over the years, I have wondered what is the mysterious relationship between a word and its real meaning. Words are often a necessity. Words, like chairs and tables, are necessary tools for navigating the everyday world. But it is all too easy to let the word itself take first place. The essence is meaning. Silence already has a meaning, meaning that is searching to be recognised through a world of changing forms and sounds.

Our lazy habit is to generalise. Look closer, however, and you will discover that, much as the atom – once opened – contains a universe, in the same way if we linger fondly within a phrase, we find within each word and every syllable that the resonances are never twice the same.

- Tip of the Tongue: Reflections on Language and Meaning by Peter Brook is published as a £7.99 paperback on 14 September by Nick Hern Books

- Peter Brook in conversation at the National Theatre, London, Thursday 14 September, 6 pm

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment