Georges Simenon: The Krull House review – timely revival for a noir masterwork | reviews, news & interviews

Georges Simenon: The Krull House review – timely revival for a noir masterwork

Georges Simenon: The Krull House review – timely revival for a noir masterwork

Xenophobic hatred leads to disaster in this 1939 classic of bigotry and menace

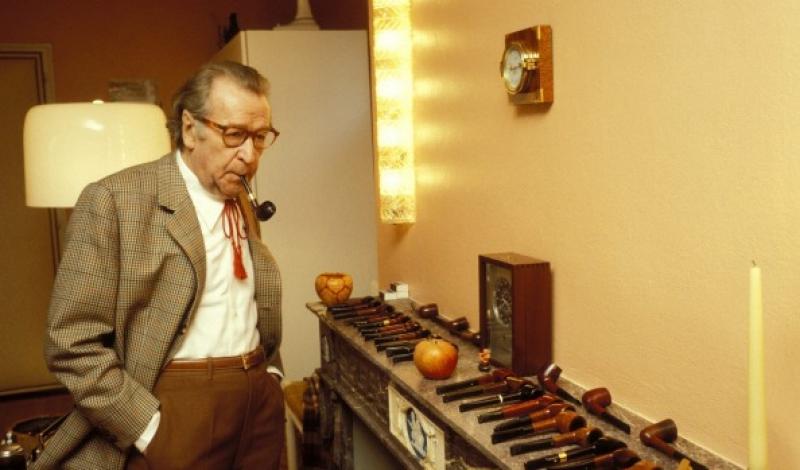

Georges Simenon began to write his Inspector Maigret mysteries in the early 1930s. Not long after after, the famously productive Belgian-born novelist – who could polish off a Maigret inside a fortnight – branched out into more ambitious, less formulaic but equally addictive stories of guilt, obsession, murder and the treacherous ambiguities of justice. These romans durs, “tough novels”, were painted in the deepest shades of noir.

Over the past few years Penguin have not only reinvigorated the Maigret series with their ongoing project to publish new editions of all 75 of them, re-translated by some of the top names in the business. They have reissued, again in refreshed versions, several of the finest romans durs. After such prose bombshells as The Mahé Circle and The Blue Room, this chilling, compelling new translation of The Krull House – from the excellent Howard Curtis – revives one of the most incisive of Simenon’s non-series works. Published first in 1939, on the eve of the Second World War, its story of violent death and disputed guilt sits within a sinister framework of prejudice, scapegoating, persecution and mob frenzy. Timely then, topical now: The Krull House traces the consequences, for individuals and a whole community, of the belief that “the Foreigner” embodies “the cause of all the ills in the world”.

In their workaday canal-side town in northern France, the Krull family represents the foreign element that arouses fear and even hatred. German incomers, their very presence here in the aftermath of the Great War – sequestered in the grim waterside dwelling where they sell supplies and grog to passing bargees and carters – affronts their French neighbours. In its lonely spot by the canal whose itinerant workers fund the family enterprise, “no longer in the country” but merely “on the edge of town”, the Krull house stands as a grey emblem of the anxious, marginal immigrants who inhabit it. Aunt Maria, who runs the business and the household, has “suffered for so many years from being German that she has lost count”. Patriarch Cornelius, who has never learned French, weaves baskets in his cloister-like workshop. Cowed daughters, Liesbeth and Anna help out in the shop while their morose brother, Joseph, studies hard for his medical exams. Having a respected doctor in the family will, the Krulls trust, improve the local standing of this “clan apart”.

Into this sombre and shuttered home, Cousin Hans arrives – illegally – from Germany as a bringer of mischief, a young lord of misrule. A footloose chancer and con man who claims (without evidence) that he has fled political harassment in Germany, Hans carries “mysterious thoughts” into the house. Cynically, he seduces the naive, solitary Liesbeth. He alarms the repressed Joseph with a swaggering, rule-busting confidence unknown to his forever nervous relatives. To Hans, as he swindles 5000 francs from the grocer father (another German outsider) of the suitable boy intended as a match for Liesbeth, the Krulls have failed both at integration and at proud detachment. In this novel full of limits, lines and borders, first neurotically patrolled then catastrophically breached, he decides that they come across to the suspicious townspeople as both “too foreign” and “not foreign enough”. When they appease the locals, they provoke contempt. When they stand apart, they inspire resentment. Perfect scapegoats, custom-made victims, the Krulls can never win.

The body of a girl, raped and strangled, is recovered from the always-ominous canal. She is Sidonie, daughter of the drunken, foul-mouthed barge-dweller Pipi, who haunts the Krulls’ makeshift bar. Suspicion settles first on Pipi’s shambolic consort, Potut, then, more worryingly, on Joseph. His buttoned-up demeanour conceals an angry, frustrated soul given to trailing young women after dark and spying on couples as they make love in the open air. Rumours spread. Gossip turns toxic. As the air thickens through sultry summer days (no one conjures atmosphere better, or more briefly, than Simenon), a static charge of foreboding crackles around the Krulls. We soon reach that moment just “before a powder-keg explodes”. A broken window-pane proclaims “the first wound to the house”. Then come the scrawled graffiti: “Murderers” first of all, then “Kill!”. Crowds gather; surly, drunk, provocative. Hans, with his sly knack of coming out ahead in every transaction, snatches the role of arbiter and interrogator for himself. Joseph admits his night-prowling habits but claims to have seen another man struggling with Sidonie shortly before her death. When a senior inspector calls to question the family, he declares “It stinks of Kraut here!”

The body of a girl, raped and strangled, is recovered from the always-ominous canal. She is Sidonie, daughter of the drunken, foul-mouthed barge-dweller Pipi, who haunts the Krulls’ makeshift bar. Suspicion settles first on Pipi’s shambolic consort, Potut, then, more worryingly, on Joseph. His buttoned-up demeanour conceals an angry, frustrated soul given to trailing young women after dark and spying on couples as they make love in the open air. Rumours spread. Gossip turns toxic. As the air thickens through sultry summer days (no one conjures atmosphere better, or more briefly, than Simenon), a static charge of foreboding crackles around the Krulls. We soon reach that moment just “before a powder-keg explodes”. A broken window-pane proclaims “the first wound to the house”. Then come the scrawled graffiti: “Murderers” first of all, then “Kill!”. Crowds gather; surly, drunk, provocative. Hans, with his sly knack of coming out ahead in every transaction, snatches the role of arbiter and interrogator for himself. Joseph admits his night-prowling habits but claims to have seen another man struggling with Sidonie shortly before her death. When a senior inspector calls to question the family, he declares “It stinks of Kraut here!”

We know that it can only end badly. Simenon, as cunning as he is controlled, still shocks with the eventual dénouement – not only in terms of those who suffer, but those who don’t. The Krulls will pay a price for their stubborn foreignness, their scapegoat status, their botched assimilation – “too much, but not enough”. But which members will face the fatal bill? The restive townsfolk treat the stand-offish Germans, in their “in-between zone” by the water, as proxies or emissaries for a time that tramples on the reassuring frontiers and divisions of the past. With impeccable insight, and fastidious prose, Simenon lays bare the internal and external harm dealt to insecure outsiders in a “chaotic universe” that swirls around them as murkily as the canal itself. In our new age of xenophobia and groupthink, The Krull House harbours a still-vital warning behind its gloomy doors.

- The Krull House by Georges Simenon, translated by Howard Curtis (Penguin Classics, £10.99)

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Add comment