Absorbed meets Allison at the end of her relationship with Owen. They are at a New Year's Eve party when she realises that their 10-year partnership has wound down. So far, so normal. But even within this introduction, we are drawn into Allison's head, the promise clear that the anxieties she hears on a daily basis will become secondary characters to the plot itself.

It is after the party, in their hotel room, that Allison's paranoia transforms into the titular experience; instead of allowing Owen to break up with her, Allison absorbs him: “I began to feel that I was sinking… we are becoming one. I wasn’t scared, but Owen was.” The crux is revealed that ties this story into the transgressive canon of New Ruins, a new collaboration between Dead Ink and Influx Press that focuses on the “porous and uncanny boundary … of literary and genre fiction”. With Whitehead's boundary-blurring, darkly funny debut as its first release, the imprint has definitely declared its intentions.

The prose gives us a beautiful blur of surreal supernatural activity and down-to-earth realism. Whitehead builds a relatable main character, Allison, whose self-fulfilling neuroses confidently anchor the novel in a familiar world. Her main fear is the thought of living without Owen, the person she has relied on for so long and around whom so much of her life revolves. Without him, she struggles to conceptualise her sense of self: “I felt like being Owen's girlfriend was the most stable identity I had ever had”. Even once she has absorbed Owen, emboldening herself with his masculine confidence, the question at the heart of her inner-monologue remains: who I am alone?

Allison’s absorption of Owen signals a reckoning with her physicality. The battle between mind and body lies in the subtext for a majority of the novel. From the moment of absorption, Allison experiences varying levels of intense pain, the first of which is described only as a “cramp” but later on results in her curled up in public, “battling the pain, trying to hold it away from my face”. It is then that she makes the connection. The intense menstrual cramping “wasn’t a normal pain … it was connected to Owen.” The connection between her body’s innate pain sensors and the existence of her boyfriend is blurred, which in turns obscures her own sense of self. Allison begins to lose trust in the identity she built as “Owen’s girlfriend”. She begins to build a new self, one constructed around the space Owen used to physically exist in and around the repleteness now Allison feels having contained him.

Allison’s absorption of Owen signals a reckoning with her physicality. The battle between mind and body lies in the subtext for a majority of the novel. From the moment of absorption, Allison experiences varying levels of intense pain, the first of which is described only as a “cramp” but later on results in her curled up in public, “battling the pain, trying to hold it away from my face”. It is then that she makes the connection. The intense menstrual cramping “wasn’t a normal pain … it was connected to Owen.” The connection between her body’s innate pain sensors and the existence of her boyfriend is blurred, which in turns obscures her own sense of self. Allison begins to lose trust in the identity she built as “Owen’s girlfriend”. She begins to build a new self, one constructed around the space Owen used to physically exist in and around the repleteness now Allison feels having contained him.

The juxtaposition between the ease with which Allison accepts herself and the derivative judgement she passes onto those around her is fuel for her reactions to her newfound solitude. People's spiritual practices are yet another way for her to look down on them, while she holds herself to a wildly different standard, knowing that the desire to retain her faith is nestled deep within her: “I had created a version of myself that dismissed anything vaguely spiritual as nonsense … I longed to find a deeper understanding … a grip on the world that would allow me to live as everyone else seemed to: with purpose”. This thread, which Whitehead keeps pulling through the novel, is what makes the book so gripping.

Allison’s experience of wavering between external derision and internal desire is often painfully relatable. She belongs to a generation caught between religion and secularism, and her birth parents’ faith is a shifting anchor to which she tethers her confusion and her condescension, but the unreliability of this knowledge means it conveys nothing concrete. It is the intervention of Odile – a “hippy” – and the open arms with which Allison is welcomed into the world of incense and rituals that eventually gives Allison the power to embrace nuance and be “comforted by the notion that [she] could carve a personality, possibly even a religion, out of a feminist identity that [she] had failed over and over.”

When she was part of the indivisible unit of “Allison and Owen, Owen and Allison”, there was nothing tethering Allison to a foundational sense of self. The introduction of Odile, and the self-analysis into which Allison is forced by losing her anchor (Owen) brings her to this realisation. Women often feel the pressure that Allison caved into: the expectation to define oneself by external markers. By taking Owen into herself, Allison is forced to reckon with what she genuinely feels. She ends up embracing a new feminist identity and redefining what constitutes being “alone”.

Whitehead is also interested in exploring the ways women form relationships with each other. Distinct queerness underlies the relationships Allison has with other women, even as she fluctuates between resistance, jealousy, and desire. She begins to build a relationship with Helena, a female friend of Owen's, and the stereotypical route of queer women's relationships is played out for us in fast-forward: they meet, acknowledge their desire, and subsequently merge until they become indistinguishable from one another. Allison expresses confusion as to whether her desire is to be with Helena or to be Helena: “she was everything I wanted, everything I wished I could be”. Cleverly interweaving these ideas with the concept of absorption, Whitehead forces us to reconsider what Allison's role in her own life actually is. The motive behind her absorption of Owen – if a motive exists at all – can be read as a wish to free herself from a heterosexual relationship, but equally as a desire to become an individual, or as the desire for “ultimate intimacy”. The systems of capitalism and patriarchy make individual desire difficult to understand or acknowledge; this consciousness is built into Allison as a character, through her permanent link to Owen.

Whitehead’s language is also reflective of the fluid nature of absorption. It rides the fine line between disgust and humour: there’s a face “as pale and swollen as a soggy slice of thick white bread”, and Allison describes how “her organs had become entangled in my skin”. Even as Allison’s anxieties are commonplace, her movement through life is sticky and complicated, heightened by the book’s supernatural lens and its elements of body horror.

That said, even as Absorbed pushes at generic boundaries – always asking “What if?” – the book is ultimately a study in relatability. Whitehead has created a rich and full character who enables an exploration of identity and anxiety, femininity and queerness, selfhood and romantic relationships – all under the guise of a nightmare come true. Allison is our entry-point into ourselves: the reader is invited to self-analyse along with her. Whitehead delves into the question of what lies beneath the surface of the people we meet; it turns out the answer is complicated, gross, and utterly compelling.

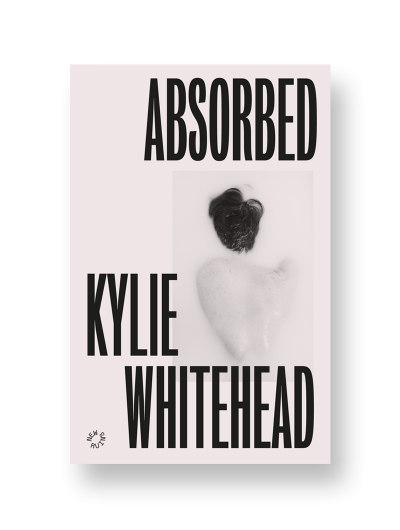

- Absorbed by Kylie Whitehead (New Ruins, £9.99)

- Read more book reviews and features on theartsdesk

Add comment