Muhsin Al-Ramli: 'During Saddam’s regime at least we knew who the enemy was' - interview | reviews, news & interviews

Muhsin Al-Ramli: 'During Saddam’s regime at least we knew who the enemy was' - interview

Muhsin Al-Ramli: 'During Saddam’s regime at least we knew who the enemy was' - interview

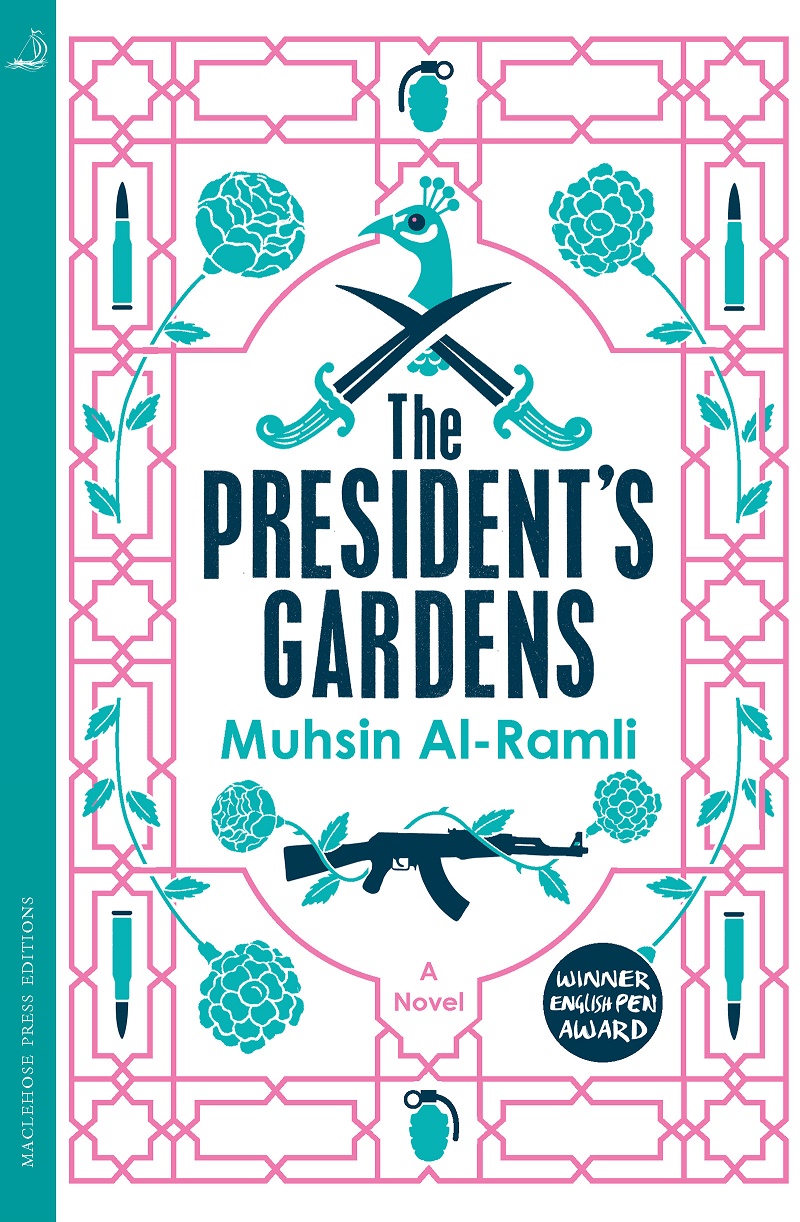

Iraqi author of the acclaimed novel The President’s Gardens on life under Saddam Hussein and after

Saddam Hussein’s name is never mentioned in The President’s Gardens, even though he haunts every page. The one time that the reader encounters him directly, he is referred to simply by his title. In a novel of vivid pictures, the almost hallucinogenic image of the President turning the ornamental gardens around him into a bloodbath is one of the most unforgettable.

The author Muhsin Al-Ramli is well acquainted with the psychotic precision of Hussein’s brutality, and refuses to name him because he feels it would “dirty” the book. “At 8pm on 18 July, 1990, Saddam Hussein’s regime killed my brother [the poet Hassan Mutlak – known as the Lorca of Iraq],” he tells me. “He wasn’t in the army, but he had been plotting a coup with some of Saddam’s soldiers. The plot was discovered at the last moment. They were arrested and tortured – then the soldiers were killed with bullets, and my brother, because he was a civilian, was hanged. They didn’t return the bodies to the families of the military men till the families paid the cost of the bullets they had used to kill them.”

This is not the only tragedy that has marked the 50-year-old Al-Ramli’s life, yet the sleek well-preserved man I talk to in the vast darkened lounge of Russell Square’s President Hotel does not flaunt his emotional scars. On the contrary, he is distinguished by the fierce, almost relentless, humour I have encountered when interviewing other survivors from totalitarian regimes. Anger and laughter are closely intertwined in his conversation and prose – when challenged on this, he replies, “when situations reach their limit of tragedy and pain there is no other way of expressing this than through sarcasm and irony.” His great literary hero is Cervantes – he did his doctoral thesis on Don Quixote into Arabic – and he points out how the comic ebullience of the Spaniard’s masterpiece was, in essence, a response to “suffering so much under the Inquisition”.

I almost stopped breathing I was so afraid

The President’s Gardens – his third novel – has been ecstatically hailed since its translation into English by Luke Leafgren, not least by Robin Yassin-Kassab in the Guardian who describes it as an “epic account” of Iraq’s sufferings since 1980. It tells the story of modern Iraq through a portrait of three friends: Tariq the Befuddled, Abdullah Kafka, and Ibrahim the Fated. Deftly Al-Ramli sketches the joys and pains of growing up in a village (evocative of his own birthplace, Sudara, in northern Iraq), infusing tragedy with comedy, the epic with the intimate, and the real with the surreal.

It is Ibrahim who witnesses Saddam carrying out the execution in his Versailles-like gardens – an episode, Al-Ramli tells me, taken from a real-life account by one of his relatives. Amid the poisoned perfection of perfumed fountains and manicured flowerbeds, Ibrahim is employed – as a “reward” for loyal service in the army – to bury the corpses of Saddam’s torture victims. The lugubrious Abdullah, nicknamed “Kafka” because of his melancholic nature, does military service with Ibrahim, yet his fate is to be imprisoned in Iran where he witnesses Shiite oppression under Ayatollah Khomeini. Tariq the “Befuddled”, so-called because he is easily seduced by any new idea, is the most fortunate of the three. He becomes an imam, is spared military service and ultimately prospers, even as he witnesses the tragedies of those living in the village around him.

Though his family suffered much under Saddam Hussein – Al-Ramli remembers that the one time he saw Hussein, while on military service “I almost stopped breathing I was so afraid” – the novel is striking for its lack of partisanship. In the arresting opening image, nine severed heads are delivered to the village in banana crates. Al-Ramli points out that this echoes the fate that befell nine of his relatives in 2006, after Saddam had fallen from power. “During Saddam’s regime at least we knew who the enemy was,” he says. “Since he fell, we have encountered multiple enemies, both inside and out of the country. The Americans and the British left our borders vulnerable. I start my novel when I do, because that was the beginning of two of the most difficult years in Iraq’s history.”

The scene where the Americans are the main destroyers – set during the first rather than the second Gulf War – is the most apocalyptic. Ibrahim the Fated – whose philosophical acceptance of suffering means, according to Al-Ramli, that he represents Iraq – is fighting in Kuwait. When the allied forces begin their attack on Saddam’s forces, the desert is quickly turned into “a sea of fire and iron”. Ibrahim and his friend Ahmad try to escape, fleeing as far as the international highway connecting Kuwait and Basra before the American B-52s arrive. “What they saw was a true hell in all its horrors… The road was transmogrified into an explosion of fire, smoke, limbs, blood, destruction, ashes, death.”

The scene where the Americans are the main destroyers – set during the first rather than the second Gulf War – is the most apocalyptic. Ibrahim the Fated – whose philosophical acceptance of suffering means, according to Al-Ramli, that he represents Iraq – is fighting in Kuwait. When the allied forces begin their attack on Saddam’s forces, the desert is quickly turned into “a sea of fire and iron”. Ibrahim and his friend Ahmad try to escape, fleeing as far as the international highway connecting Kuwait and Basra before the American B-52s arrive. “What they saw was a true hell in all its horrors… The road was transmogrified into an explosion of fire, smoke, limbs, blood, destruction, ashes, death.”

Al-Ramli himself was on forced military service during the Kuwait war and witnessed the immediate aftermath of the scene. In a moment in the novel that evokes the magical realism of another of his literary heroes, Gabriel García Márquez, he describes a dog with a human face approaching Ibrahim as he lies amid the corpses left by the bombers. “[The] monstrosity of the sight terrified him. When the dog turned away, Ibrahim realised it did not have human features, but rather it was carrying someone’s severed head in its jaws, the face turned forward.”

The President’s Gardens represents a significant maturation of style for Al-Ramli. Its virtuosity and breadth makes it different from the acclaimed yet more obviously raw and angry Dates on My Fingers. By showing the universality of evil – refusing to ascribe it more to one side than another – Al-Ramli has made this nothing less than a great novel about life and death. The intense joys of love for a child, the complex pleasures of friendship, or the simple delights of swimming in the Tigris are evoked every bit as vividly as the terrors of destruction.

Yet this same refusal to embrace partisanship also means that Al-Ramli can no longer go home to visit his family. The bookish child of a village cleric – “my mother wanted to burn my books because she thought I would go mad,” he laughs – he fled to Spain in 1995. Now he teaches at the Saint Louis University in Madrid. But his family still lives in the village where he was born, which – at the time we meet – is under the control of Daesh.

“They killed one of my beloved nieces because she had been a monitor for an election – they killed her with a sword in the town square,” he says, eyes glistening. It’s not just Daesh he fears – “because I’ve spoken so much about Iran, [Shiites] want to kill me too. Then there are those who still believe in Saddam’s legacy – “A lot of Arab people, Palestinians, Moroccans, continue to think of Saddam Hussein as a hero. They hate me and reject me for the way I’ve portrayed him.”

His eyes glitter. “But I wrote this book to speak to young Iraqis and help them understand their country. Even now, every day some atrocity is taking place in Iraq. They are robbing museums, destroying archaeology, breaking civil society and the links that bring the community together. One of the most important jobs that literature has is to explain the memories that are being wiped away every day.”

- The President's Gardens is published by Quercus Books (£12.99)

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Add comment