Selina Todd: Tastes of Honey review – Salford dreams of freedom | reviews, news & interviews

Selina Todd: Tastes of Honey review – Salford dreams of freedom

Selina Todd: Tastes of Honey review – Salford dreams of freedom

The life and legacy of Shelagh Delaney, artistic godmother to Corrie – and The Smiths

In the late 1950s, a photo technician from Salford suddenly became “the most famous teenager in Britain”. Shelagh Delaney was 19 when she sent the script of A Taste of Honey to the radical director Joan Littlewood. Within a matter of weeks, in May 1958, Theatre Royal Stratford East had staged it – sensationally, to a welcome that mixed bouquets and brickbats.

For a Salford girl born in 1938, daughter of an Irish bus driver and a local factory worker, a childhood in the immediate aftermath of war offered doors that partly opened, only to swing shut. A professor of modern history at Oxford, Selina Todd registers the height of the walls that a bright but non-conforming working-class girl had to scale even as the post-1945 Welfare State took root. Unusually, the smart but “unbiddable” Shelagh (she had changed her name from “Sheila” to sound more Irish) transferred from a progressive secondary modern school to the local girls’ grammar, Pendleton High. There she languished in a stiflingly conservative place where the pupils were still channelled into lowly office jobs as a prelude to their – seemingly inevitable – destiny of marriage and motherhood. A convalescent spell in the charge of grimly repressive nuns had cemented the “profound scepticism towards authority” nurtured by a hard-pressed but free-spirited home. Salford, though, already bred its artistic rebels, such as the actor Albert Finney and artist Harold Riley – both friends, and later lovers, of Delaney. In Manchester, where the council planned a “cultural quarter”, a production of Beckett’s Waiting for Godot became her “chief inspiration to write”. Down in London, the advent of the Look Back in Anger generation (John Osborne and Arnold Wesker above all) signalled that outsiders might now barge through a few hallowed portals of drama.

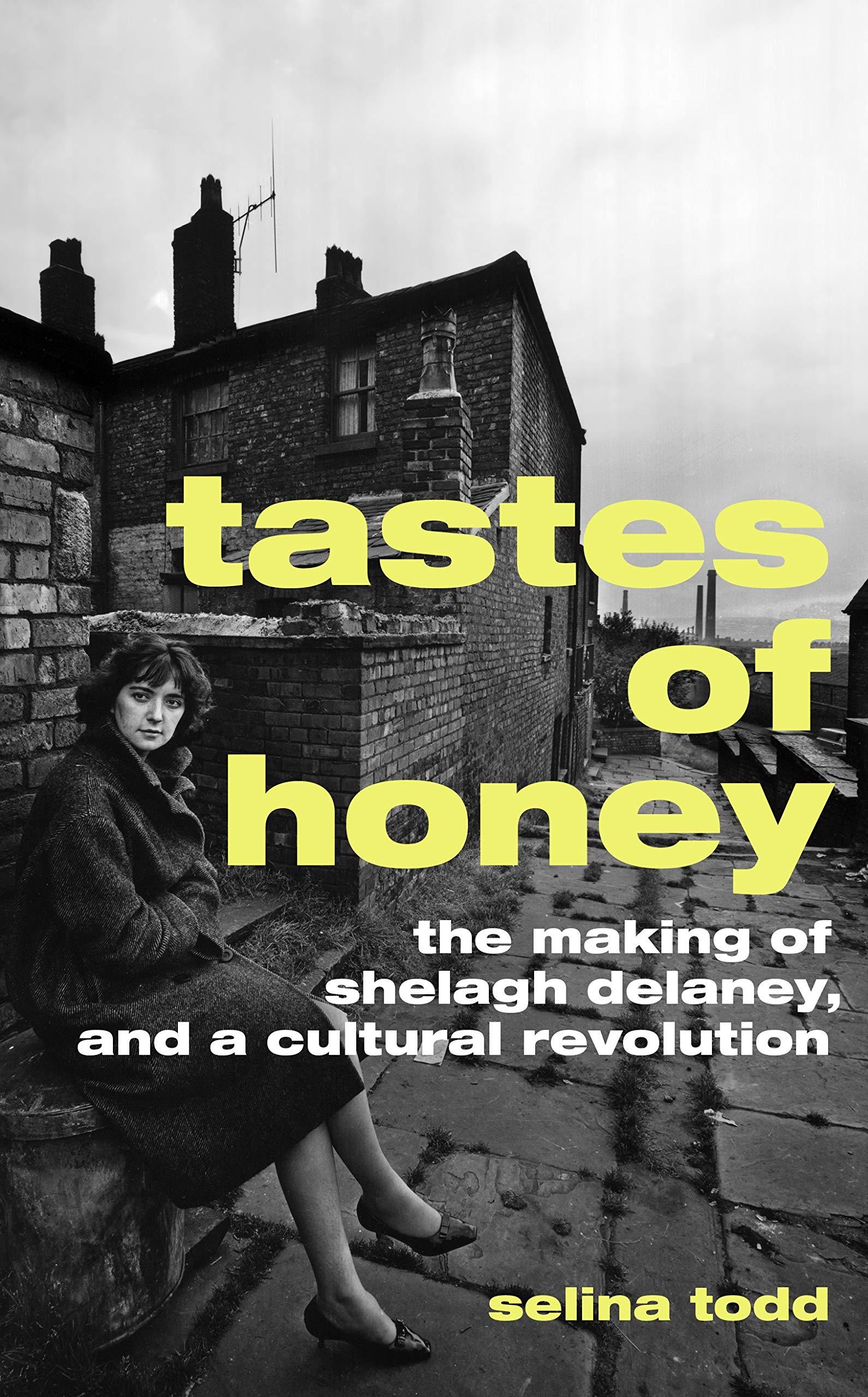

Male outsiders, that is. Todd explains how the assumptions of gender as well as class shackled Delaney (pictured above in Salford) as she sought to escape the “miasma of falsity” that writer Alan Sillitoe condemned in the conservative British culture of the 1950s. Yes, Littlewood’s prompt embrace of A Taste of Honey revealed a widespread hunger for change. But even that duchess of rule-busting drama tried to tone down the script: her revisions pushed the characters towards stereotype, and downplayed Delaney’s insights into “the power of sex and class to shape people’s lives” in favour of a more familiar “generational clash” between mother and daughter. Diluted or not, the play crested a new wave of cultural dissent, adored by its admirers but scorned by diehards such as the Spectator critic who dubbed it “the inside story of a savage culture observed by a genuine cannibal”. Todd shows in jaw-dropping detail the depth of the hostility to Delaney and her unapologetic work: Salford council practically ran an anti-Taste of Honey rebuttal and disinformation unit. That bombed; in contrast, her supporters advanced – above all, perhaps, when her disciple Tony Warren went on to create the Delaney-flavoured Coronation Street for Granada in 1960 (even though she refused to write for the soap). The ungrateful “cannibal” had meanwhile thrived. West End and Broadway transfers, then a film (the producers initially wanted Audrey Hepburn for the lead; more plausibly, Rita Tushingham took the role) gave Delaney youthful affluence, and leisure. A follow-up play, The Lion in Love, extended her themes but, Todd admits, “does lack pace and resolves nothing”. The later Sixties saw a couple of successes: above all the picaresque film Charlie Bubbles, a sort of “joint autobiography” for Delaney and Finney, its director and star.

Male outsiders, that is. Todd explains how the assumptions of gender as well as class shackled Delaney (pictured above in Salford) as she sought to escape the “miasma of falsity” that writer Alan Sillitoe condemned in the conservative British culture of the 1950s. Yes, Littlewood’s prompt embrace of A Taste of Honey revealed a widespread hunger for change. But even that duchess of rule-busting drama tried to tone down the script: her revisions pushed the characters towards stereotype, and downplayed Delaney’s insights into “the power of sex and class to shape people’s lives” in favour of a more familiar “generational clash” between mother and daughter. Diluted or not, the play crested a new wave of cultural dissent, adored by its admirers but scorned by diehards such as the Spectator critic who dubbed it “the inside story of a savage culture observed by a genuine cannibal”. Todd shows in jaw-dropping detail the depth of the hostility to Delaney and her unapologetic work: Salford council practically ran an anti-Taste of Honey rebuttal and disinformation unit. That bombed; in contrast, her supporters advanced – above all, perhaps, when her disciple Tony Warren went on to create the Delaney-flavoured Coronation Street for Granada in 1960 (even though she refused to write for the soap). The ungrateful “cannibal” had meanwhile thrived. West End and Broadway transfers, then a film (the producers initially wanted Audrey Hepburn for the lead; more plausibly, Rita Tushingham took the role) gave Delaney youthful affluence, and leisure. A follow-up play, The Lion in Love, extended her themes but, Todd admits, “does lack pace and resolves nothing”. The later Sixties saw a couple of successes: above all the picaresque film Charlie Bubbles, a sort of “joint autobiography” for Delaney and Finney, its director and star.

Delaney, though, soon had to weather the mid-career doldrums of the prodigy and pioneer. She never cared to work too hard, savoured the fruits of her success (“I loved the parties, I loved the cocktails”), but found too that some grand gates in the palace of art remained locked for the likes of her. Todd shrewdly notes that the open endings and unresolved conflicts of her short stories and radio plays reflect not just an artistic problem with closure but the shared absence of direction that resulted from “unprecedented generational change”. Delaney did find a centre in raising her daughter Charlotte (a crucial source for this book), whose – mostly absent – father was New York writer and agent Harvey Orkin, and in her rambling house in Islington. Todd never mentions that Delaney's home stood just one street away from Noel Road, where another taboo-trampling dramatist, Joe Orton, lived and died (murdered by his lover). Sometimes, the hinterland of her biography feels unduly narrow, especially as it promises not just a portrait of the solitary artist but the broader landscape of a “cultural revolution”.

In the mid-1980s, Delaney had the chance to prove her enduring talent – and relevance – when she scripted Dance With A Stranger for director Mike Newell. The story of Ruth Ellis, last woman to be hanged in Britain, drew from her “the hardest and most worthwhile writing I’ve ever done”. Todd perceptively treats the screenplay as a belated partner for A Taste of Honey: two panels in an extraordinary diptych about working-class women’s lives, hopes and burdens in a society where their freedom often amounts to no more than a slogan, or a mirage. As for Delaney, she thoroughly enjoyed her autonomy, and wrote some strong new drama – notably for radio. Todd argues, though, that the cultural climate had turned against her in the Thatcher era, when “the arts were a luxury again”. I think she neglects the new movements that brought seldom-heard voices to stage and screen in the 1980s and afterwards (later working-class playwrights and directors from Lee Hall to Winsome Pinnock, Shane Meadows to Liz Lochhead, go unnoticed). However, her background as a social historian pays dividends when she traces the persistent appeal of Delaney’s voice and inspiration – not just for local lasses and lads (the lyrics of Salford’s own Steven Patrick Morrissey and The Smiths owe a profound debt to her) but for young women seeking liberation in closed societies from Communist Czechoslovakia to Catholic Italy.

In the mid-1980s, Delaney had the chance to prove her enduring talent – and relevance – when she scripted Dance With A Stranger for director Mike Newell. The story of Ruth Ellis, last woman to be hanged in Britain, drew from her “the hardest and most worthwhile writing I’ve ever done”. Todd perceptively treats the screenplay as a belated partner for A Taste of Honey: two panels in an extraordinary diptych about working-class women’s lives, hopes and burdens in a society where their freedom often amounts to no more than a slogan, or a mirage. As for Delaney, she thoroughly enjoyed her autonomy, and wrote some strong new drama – notably for radio. Todd argues, though, that the cultural climate had turned against her in the Thatcher era, when “the arts were a luxury again”. I think she neglects the new movements that brought seldom-heard voices to stage and screen in the 1980s and afterwards (later working-class playwrights and directors from Lee Hall to Winsome Pinnock, Shane Meadows to Liz Lochhead, go unnoticed). However, her background as a social historian pays dividends when she traces the persistent appeal of Delaney’s voice and inspiration – not just for local lasses and lads (the lyrics of Salford’s own Steven Patrick Morrissey and The Smiths owe a profound debt to her) but for young women seeking liberation in closed societies from Communist Czechoslovakia to Catholic Italy.

Although comfortable, Delaney’s final decades (she died in 2011) do leave the reader with a sense of waste. Blame it on a conservative backlash, on the waning of her creative zest, or on her refusal to treat writing as a bourgeois treadmill, but we’re missing another half-dozen or so works of the Dance With A Stranger calibre. She could certainly have written them. Should have? No: Shelagh Delaney rightly fought against the guilt-mongers who insisted that working-class achievers must forever (as Albert Finney put it) “go on being supposed to do things, obliged to do things”. The task now is to wedge open those doors securely for her successors, whatever their origin. Meanwhile, the wild, witty and cheeky kid from Ordsall still shows us how to celebrate despised and overlooked lives. As Jeanette Winterson says, her example shines “like a lighthouse – pointing the way and warning about the rocks underneath”.

- Tastes of Honey: the making of Shelagh Delaney and a cultural revolution by Selina Todd (Chatto & Windus, £18.99)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Add comment