Motion Sickness (1991) is the second novel published by the writer, art collector and cultural critic Lynne Tillman. It is difficult, to her credit, to say what it is really about – what makes Tillman a formative figure for much contemporary fiction is a capacity for formalised evasion, for writing a sparse language that nonetheless feels strangely interior to itself. My attempt at a paraphrase: an unnamed American narrator is travelling across Europe in the twilight decades of the Cold War, making friends with no one and everyone in particular. She has an affair with a Yugoslavian in Budapest and Northern Italy, works as a typist in Paris, meets an art historian obsessed with theories of Diego Velasquez’s Las Meninas (1646).

In the wake of the novel's British reissue, we spoke across the Atlantic over the phone. As well as covering some of the biographical facts informing recent her (re-)publications – Motion Sickness, Mothercare – we talked about the current status of fiction, the art of omission, and novelistic qualities in Velasquez.

Alice Brewer: Most introductions to interviews with you begin by listing the various forms of writing you’re known for. I wanted to begin asking about what you think the novel manages to do that other forms of writing can’t.

Lynne Tillman: Fiction is a very benighted form now, at least in my country. Nonfiction is understood as truth, and somehow fiction and verisimilitude don’t seem to mean telling a true story. It’s the way you tell a story that makes it true: you can talk about a fact – for example that there was a sperm stain on Monica Lewinsky’s dress – but its meaning isn’t plain. You can make a story from that, from Monica Lewinsky’s point of view – why she kept the dress, why she didn’t have it cleaned – which is much more interesting than just the fact of it. Novels and short stories deal with our attempts to understand this motivation, why such quote-unquote facts seem as they are. I sometimes mix the two, not to fool people, but to say that both things are true.

AB: Regarding Motion Sickness: what were you up to there? What were you answering to?

LT: I had lived in Europe for quite a number of years, had gone to Morocco and was in Turkey. The girl who left the States and thought she was never going return was a different person. It was really learning about differences in fairly concrete ways. I had not really understood before that I was American. One of the great problems with America is thinking that we are the centre of the world. Living in Europe, things were translated differently, people behaved differently, and had different expectations.

AB: What stood out as different?

LT: The [Second World] War wasn’t fought on American soil. [In Berlin] young Germans were dealing with the actions of their grandparents, the older generation was living with or trying to forget a tremendous guilt.

And when I was there in the seventies, there was, in the UK and Amsterdam, less militancy around women’s rights. Another difference was American enthusiasm. And the word intellectual, I remember using it to someone who had gone to Oxford, and then I realised it was very much about class, which wasn’t the implication in New York, at least as far as I knew: you could be from the working classes and be an intellectual. In Amsterdam, I started a cinema, modelled after the Electric Cinema in London. My father had sent me a hundred dollars to buy a winter coat, and I used it as a downpayment on this down-on-its-heels movie theatre that was no longer showing films. My Dutch friends were  amazed we hadn’t gotten a government grant, that I would use my own money.

amazed we hadn’t gotten a government grant, that I would use my own money.

AB: I really liked your essay on Andy Warhol’s a, A Novel: the ending paragraphs when you’re talking about the value of that book being the unedited quality, because how else do you know what to pay attention to until all possible data is there.

LT: Characters [in Motion Sickness] like Arlette, like Cengiz — they’re not actually composites but they are representative of certain writers, filmmakers, artists. The hardest, most important thing is what you leave out. With great writers you always feel that everything necessary is there: Edith Wharton, Henry James, Jean Rhys. [James] Baldwin’s essays more than his novels. Dennis Cooper. Learning what to leave out is a crucial matter for any art. Sculpture, painting — photography, choosing what to leave out of frame. I’ve been very struck with this when I have written some non-fiction, too. I did a book with Stephen Shore's photographs that I called The Velvet Years about Warhol’s Factory then, from 1965 to 1967. I’d interviewed all of these people who’d been at the Factory a lot, and had so much material. I’d make decisions based on what I thought readers would find most compelling, what I found most compelling. I left out gossip.

AB: It also implies a sort of unhinging from medium specificity, almost as if it’s secretarial work or collage. Motion Sickness in particular makes me want to use spatial terms to describe it: the postcards, the location-subsections. How does visuality inform your writing? Why does Las Meninas loom so large?

LT: I saw it for the first time [in the Prado] finally and went back. I guess I think of it as a novel. Each of the characters plays a role, though all of those people in the painting are based on actual people. As a painting it’s a fiction, in that they represent something that we can only project into. We’re given a certain amount of detail. The infanta in the foreground is being whispered to by the two maids; in the mirror in the back, we can see the image of the king and queen, but it's not realistic. They’re not close enough to be so full. But it’s also a room that’s factually correct. I’m fascinated by – and I had Arlette fascinated by – a theory which I now having seen it don’t think is quite correct: the idea was that one third of the painting is quite abstract, quite dark.

AB: Your most recent book is Mothercare, which is about looking after a mother that you weren’t particularly attached to, employing working class, undocumented immigrant women to help you. Both before and after these biographical facts, your fiction often takes place in impermanent residences like hotels or sanatoriums, with discomforting proximity to service workers. What draws you to these places?

LT: I know that Americans aren’t supposed to be highly involved in class, but really I think this is impossible to live in this world without recognising the economic and cultural differences. I’m going to write something in my new novel about really understanding practically what being middle class is, and finding this out by being subjected to an upper class Greek family and the way they treated their employees.

In the case of Mothercare, the most difficult part of writing it was how to write about the working class employing people who were less privileged, if you want to use that word – certainly more desperate. Their reality was different from your reality meanwhile, for instance, this woman [Tillman and her sisters employed] was living with my mother, she had her own bedroom. She had – in a way – her own life but it was encapsulated in my mother’s life. I became what I thought was quite close with her, but I knew her in a very particular way because she was employed by us. The idea that we are all part of the same family is false, and troubling. We employed her for much less than we would have employed a US citizen, and we couldn’t afford to do otherwise.

AB: Does Motion Sickness – first published in 1991, before much of this had happened – read differently to you now?

LT: With every novel I write I try to do something different, though I wish in some ways I could continue. If you read enough of my novels you can see there’s a different problem or project going on. I know I repeat myself, but I kind of have a horror of it, and I even try to change style. Definitely I try to change the subject.

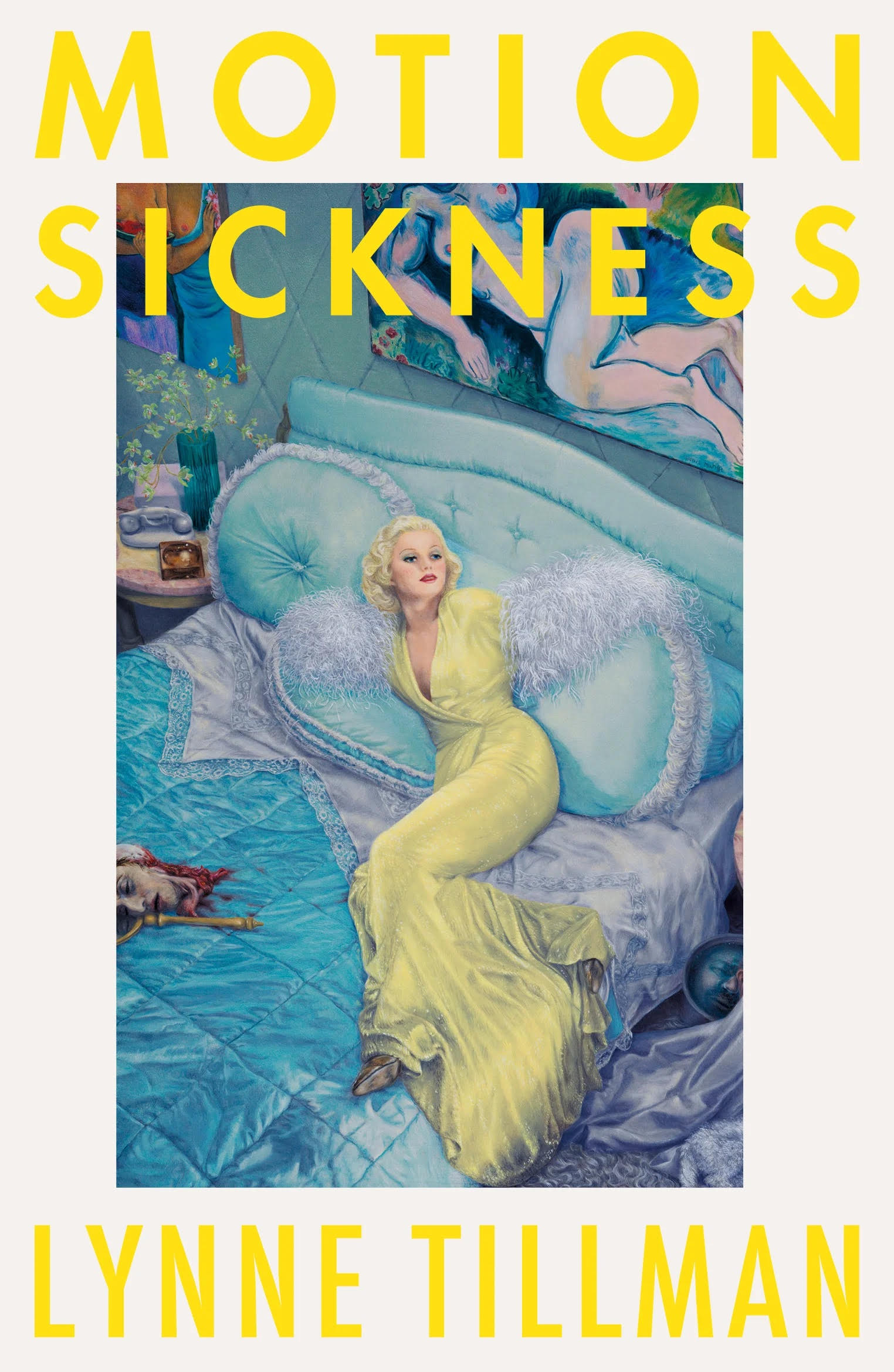

- Motion Sickness by Lynne Tillman (Peninsula Press, £10.99)

- Book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment