This is a biography like no other, more or less dictated by Lucian Freud. William Feaver spoke with the artist perhaps almost daily for nearly 40 years, visiting frequently, taking notes, recording, and being shown work in progress. The second volume of the resulting kaleidoscope – the two together, the first published last year, come to over 1,100 pages – is a mesmerising, entertaining account of Freud’s life and art. Freud’s own comments on other artists, his own paintings, and art in general, its purposes and his own aesthetic, are intelligent, enlightening and absorbing.

Feaver’s narrative is shaped by the artist himself, who is rumoured to have paid his interlocutor off with a goodly sum to make sure the result was a posthumous publication. The result is the opposite of a critical, analytical and evaluating biography, so Freud had nothing to fear if this was really the picture he wished to leave of himself. Feaver supplies the connective tissue between the remarks and observations of the artist. It is left to us to decide how truthful Freud is being about the events and relationships in his life. It is his version after all, although the author has compiled an astonishing archive of letters, interviews and conversations with friends, dealers, curators, relatives. Above all, the author seems to unreservedly admire the artist’s chutzpah, that almost untranslatable Yiddish word for brazen nerve, presumption, arrogance, guts and effrontery, which is one of the defining characteristics of Freud’s personal and professional life: he was always dismissing his dealers, and going off them and his framers, even his clients, not to mention his sitters. He described himself, justly, as completely selfish.

Freud was full of contradictions. In his later years, he became increasingly irascible, continually referring to his need for privacy and his irritation at paparazzi, even as he also backed into the limelight. His personal life was a web of endless affairs well into his eighties, despite being affected both by hypochondria and ill health. The final years are a sad coda with some mental confusion. Some of the confusion pertained to family, many of whom he lavishly if capriciously supported. There were at least fourteen acknowledged children, two from his first marriage to Kitty Garman, herself the illegitimate daughter of the sculptor Jason Epstein. But there may be and probably are several more – one lover amused herself by trying to count. There are so many offspring in a rather complex web that some kind of family tree wouldn’t have gone amiss: every few pages you have to try and remember who was who, and who is who. It is also a continual motif for various children, even into their middle age, to get in touch, be thrilled with attention, and desolate when things go wrong; several were obviously traumatised, and four acknowledged children – the McAdams – were completely cut out of the will (Freud left, after tax, some £42m). One sued to no avail.

The capriciousness of Freud, as he went off his models, his lovers and his children, for no apparent reason other than changes in mood, is a thread throughout the book. Yet his generosity was equally astounding. Models and lovers in favour were bought flats and cars and given quite astounding sums of money, with nothing claimed back, although there were some unpleasant episodes when works of art by Freud were promised, not given or, if given, not considered to be gifts. In one instance, he asked a young woman if she would do anything he asked. Yes, she said. He demanded a loan of £200: although it was more than she had in the bank, she gave the cheque. They gambled it away together, yet she found at the end of the evening that he had put £3,500 in her back pocket, which she used to start-up her own gallery. This anecdote is typical of the power plays that infused his life.

If this were a novel, the reader would weary of the arbitrary carry-ons, which are exhausting to read about; what it must have been like to experience them, either as perpetrator or victim, is hard to imagine. But the point, of course, is that Freud was a painter who was becoming ever more famous. The book includes his commentary on his art, which, especially when allied to specific paintings and etchings, is invariably fascinating. If you are an admirer of Freud’s work, the book as a whole is like having a guided tour from the artist himself. With this in mind, it would have been helpful, although presumably prohibitively expensive, to have illustrations close to the descriptive prose. For the developments are not always clear, and the jury is still out on Freud’s ultimate stature, although of course that useful cliché “time will tell” is pertinent. The ferociously intelligent critic David Sylvester was sceptical.

Feaver himself is hardly of course dispassionate, and acts his own role as the critic, the collaborator and the curator: he is a recorder, not a biographer. He was a one-man Freudian, not only visiting Freud regularly to see works in progress, but also talking to him nearly every day for decades; socialising, writing reviews and interviews; and curating major and minor shows replete with publications and catalogues, as well as publishing several books. He tends to be dismissive, subtly or obviously, of other curators, critics and writers, from Catherine Lampert, curator of several shows in England and internationally to Geordie Greig (author of Breakfast with Lucian) and Martin Gayford (who wrote Man in a Blue Scarf). This is truly a no holds barred narrative: Freud’s own disparaging remarks about dealers, critics, and lovers of whom he is tired, are threaded through. It's so far from any politesse that it becomes curiously liberating: how often does protocol or courtesy cover up what people really think? It's not like Freud could be sued for slander or libel.

The result is an exhaustive, obsessively detailed narrative of a figurative painter who was a leading figure in the continuing vitality of representational art. It is also a picture of a particular part of the London art world: a portrait of the period in which London took a role in the world of art for the first time. But at half the length, this biography would have been twice the book.

Typically, Freud did have at least one continuing relationship of mutual respect and affection: Pluto his whippet, the perfect model and companion, succeeded by Eli, the whippet of David Dawson, Freud’s assistant.

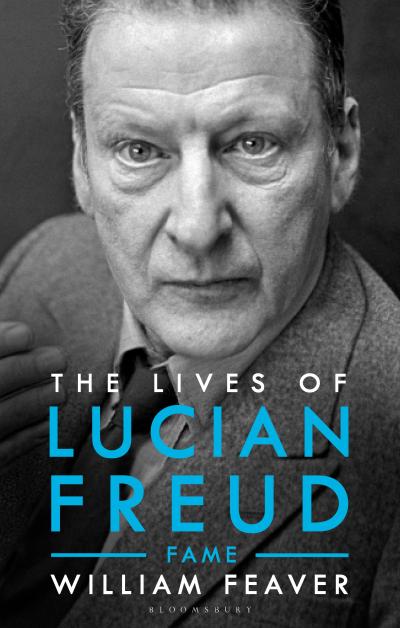

- The Lives of Lucian Freud: Fame 1968–2011 by William Feaver (Bloomsbury £35.00)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment