First Person: Pulitzer Prize winning composer David Lang on the original Jewish love story | reviews, news & interviews

First Person: Pulitzer Prize winning composer David Lang on the original Jewish love story

First Person: Pulitzer Prize winning composer David Lang on the original Jewish love story

Music, poetry and movement combine in 'Song of Songs', now running at the Barbican

I wouldn’t say that I am super religious, but I am definitely religion-curious. It is a big part of my family background, and, to be honest, a big part of the history of my chosen field, Western classical music. For the past 1000 years, the church has been the most powerful commissioner of Western music, and its most active employer of musicians.

Because of this, much of our foundational repertoire is explicitly on the subject of how music helps a listener get in the mood for a religious experience. And that is interesting to me.

Music and religion are intertwined, not just because of their shared history but because they do a lot of the same things. They both transmit important messages between people, on some mysterious, not wholly intelligible plane, and they can do that across vast time spans. They both create a community among their participants, of people coming together to share something, together. And most important to me, all participants in the experience - both the makers and the receivers - have to have faith in the power of the experience to transform them, in order to be transformed. That sounds like religion to me!

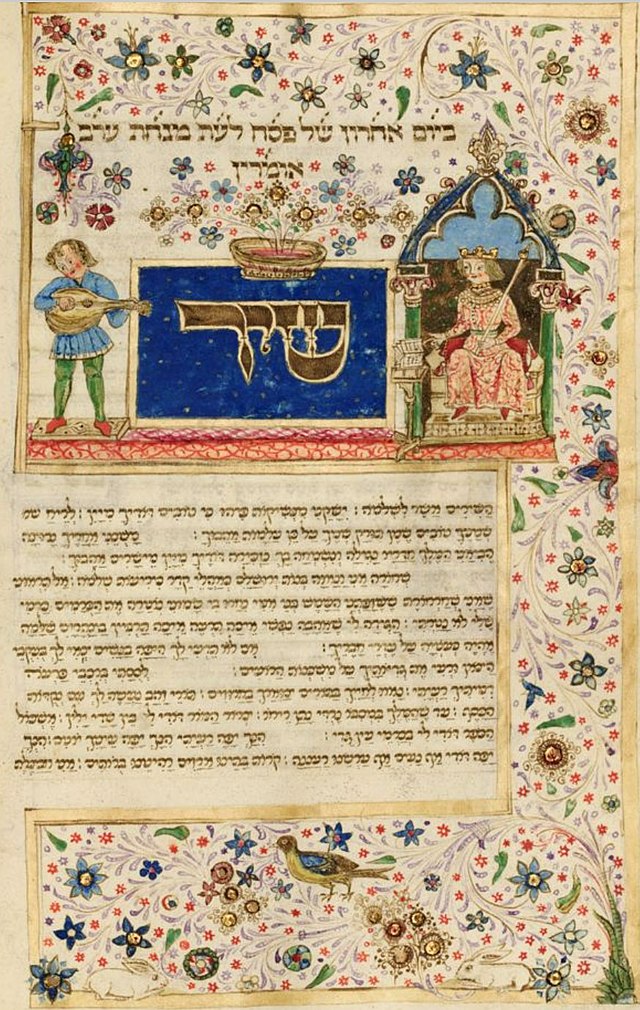

I spend a fair amount of time reading and trying to understand my own religion’s basic texts, and one text I have come back to over and over again is the Song of Songs. [Pictured right: Minstrel playing before King Solomon - ilumination for the opening verse of Song of Songs, the Rothschild Mahzor, Manuscript on parchment. Florence, Italy, 1492]..

I spend a fair amount of time reading and trying to understand my own religion’s basic texts, and one text I have come back to over and over again is the Song of Songs. [Pictured right: Minstrel playing before King Solomon - ilumination for the opening verse of Song of Songs, the Rothschild Mahzor, Manuscript on parchment. Florence, Italy, 1492]..

I remember first reading it as a boy and being shocked to discover such a passionate text among all the other, dryer and more clearly holy chapters. How could this story, about two people making out, be a spiritual text? What is such carnality doing in such a sacred place?

It turns out that there are millennia of commentary on this very subject, a history of scholarly and devout men and women seeking seek to explain what makes the Song of Songs holy. And now, adding to all their commentary, I have written five different pieces of music, based on five different readings of the text, in my own attempt to try to understand its place among the sacred.

The first of my Song of Songs pieces was written in 2008, and is called for love is strong. In that piece I read through the text while thinking about how Jewish tradition says that the Song of Songs uses the relationship between lovers as a metaphor for one’s relationship to God. The entire book is not only a metaphor, but it is made of metaphors. What is your love like? Like wine. What is your name like? Like oil pouring forth. How black am I? Like the tents of Kedar. Everything in the book begins with a comparison, leading you to the things you cannot see or feel or know by comparing them to those things you can. For my text I took every comparison in the original – every metaphor, every simile – and listed them, beginning with the wor "like". The title comes from one of the last of these comparisons – ‘’for love is strong as death,’’ which seems altogether too terrifying to be only about relationships between people.

The next version I wrote was for an entire programme devoted to music about the Song of Songs, commissioned by the Louth Contemporary Music Society in Ireland, for the amazing singers Trio Mediaeval. For this reading of the text I tried to push this "divine attributes" issue even further: the lovers in the Song of Songs have attributes, they notice things about each other, they own things, they have features that are desirable. In a love between people this would be no surprise. In a love between Man and God, however, that might mean that in this text are clues to the nature of God’s own attributes, and a record of how they might attract us.

So for this text I listed everything personal or owned that is attributed to the man and to the woman. To clarify who is speaking I started every phrase of his with "just your" and every phrase of hers with "and my".

I was very fortunate that I was able to include this piece in the film score I wrote for Paolo Sorrentino’s film Youth, and it was this version that the choreographer Pam Tanowitz heard [Tanowitz pictured left by Erin Baiano], and which made her want to include it in her own beautiful exploration of the Song of Songs. Pam enthusiastically challenged me to make even more versions of this text, to read it and re-read it, again and again, and find other ways to use the music to get to other possible meanings of the text.

I was very fortunate that I was able to include this piece in the film score I wrote for Paolo Sorrentino’s film Youth, and it was this version that the choreographer Pam Tanowitz heard [Tanowitz pictured left by Erin Baiano], and which made her want to include it in her own beautiful exploration of the Song of Songs. Pam enthusiastically challenged me to make even more versions of this text, to read it and re-read it, again and again, and find other ways to use the music to get to other possible meanings of the text.

So I did. I wrote three more pieces based on the text, all for this show.

In my piece let me come in I started with one verse in the King James version of the text, where one lover is awaiting the knock of the other on her door.

5:2 I sleep, but my heart waketh: it is the voice of my beloved that knocketh, saying, open to me, my sister, my love, my dove, my undefiled: for my head is filled with dew, and my locks with the drops of the night

I love the sense of waiting for something beautiful to happen, the anticipation of the moment, and also I love that the narrator hasn’t moved to open the door yet – the sensuousness of the waiting is more powerful for her, and for us, than the actual physicality of meeting.

Of course, these texts were originally in Hebrew, then translated and mistranslated into Greek and Latin and eventually English, and their various translations have changed the details of their various meanings. Many of these are intentional mistranslations; different Christian denominations, for example, have their own shaded versions of the text, in an attempt to lower the temperature of the original, to tone down its sensuality, or to make it seem more like a metaphor, or like a dream. I took 17 different versions of this verse, each slightly different, and then I alphabetized their phrases and got rid of all the duplicated lines, in order to make one single text, with all its interpretive angles shown. [The company of Song of Songs pictured below by Maria Baranova]. In the sense of senses I wanted to explore the sensuality of the text, noticing how the text tells the story by constantly triggering our senses. The lovers see the vines and vineyards, they smell the frankincense and myrrh, they taste the honey and the wine. Our connection to the story is deepened because the details are described to us in ways that we, ourselves, can imagine seeing, and smelling, and tasting.

In the sense of senses I wanted to explore the sensuality of the text, noticing how the text tells the story by constantly triggering our senses. The lovers see the vines and vineyards, they smell the frankincense and myrrh, they taste the honey and the wine. Our connection to the story is deepened because the details are described to us in ways that we, ourselves, can imagine seeing, and smelling, and tasting.

I wanted to catalogue all the senses in the text, so I filtered out everything except that which is seen, heard, smelled, felt and tasted, and I kept these in the order in which the story mentions them. I removed characteristics or parts of the body that would gender who is speaking, and then I rearranged the order of the senses, so that all of the seen things would be together, all the heard things, all the felt things, etc. I then ordered the senses from far to near – from sight to sound to smell to feeling to taste – so that we might feel the power of the senses grow and intensify, as they come closer to us.

And in the last piece - we were – I wanted to explore the line of commentary that says that text is supposed to give us a hint of what our lives would have been like if we had not been expelled from the Garden of Eden. The sensuousness, the calm, and the lushness of the text are all pointing us towards an alternate reality, in which beauty is all around us, and all we have to do is enjoy it. In this interpretation, the text is supposed to entice us with a vision of a life we might want, and to humble us with the knowledge of its loss. [The composer pictured right by Peter Serling]

And in the last piece - we were – I wanted to explore the line of commentary that says that text is supposed to give us a hint of what our lives would have been like if we had not been expelled from the Garden of Eden. The sensuousness, the calm, and the lushness of the text are all pointing us towards an alternate reality, in which beauty is all around us, and all we have to do is enjoy it. In this interpretation, the text is supposed to entice us with a vision of a life we might want, and to humble us with the knowledge of its loss. [The composer pictured right by Peter Serling]

The text supports this interpretation, with many detailed descriptions of the features of a garden – the vineyards, the walls, the rivers, the pomegranates. I have made a libretto out of all the garden features in the text, in the order that they are mentioned, and I have grouped them together with the preposition of where we are in relation to them – in the garden, by the streams, among the lilies, under the apple tree.

The incredible thing to me is that the text supports all these interpretations, and many, many more. After all these versions, I can’t imagine writing any more music based on this text. But I will keep reading it, so you never know.

I am supremely grateful to Pam Tanowitz, for asking me to go even deeper into a text I have always loved, and for making such elegant and meaningful movement to go along with it. And I am grateful to the lead commissioner, the Fisher Center at Bard College, and all the various co-commissioners around the world – the Barbican Centre in London, Los Angeles Opera, the Crossing Choir, Company of Music in Austria, Flagey Center in Belgium and Vox Clamantis in Estonia.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment