Van Woerkum, BBCPO, Gernon, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - a symphony of cinema | reviews, news & interviews

Van Woerkum, BBCPO, Gernon, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - a symphony of cinema

Van Woerkum, BBCPO, Gernon, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - a symphony of cinema

How an ‘image soloist’ makes film dance to music’s beat

In contrast to a classic film soundtrack played live with the film, the idea in "symphonic cinema" is that the music, and its interpretation, come first. So the conductor is literally setting the pace, and to some extent the atmosphere, while the film is controlled in real time by an "image soloist", and the visuals follow the music’s lead rather than the other way round.

It’s the brainchild of Lucas van Woerkum, who is that soloist, appearing on stage next to the rostrum like a concerto virtuoso, with a touchscreen as his instrument, and taking his bows alongside the maestro – in this case Ben Gernon, who’s done this kind of thing before with the BBC Symphony Orchestra. But it was a first for the BBC Philharmonic and Manchester. The programme was all ballet music – Stravinsky’s The Firebird and the two suites which are in fact unedited chunks of Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé (pictured below). They’re music conceived for the theatre, clearly, and to realise a visual element it’s probably less expensive to make and show a digital silent film than to bring in a complete ballet company in a staged production.

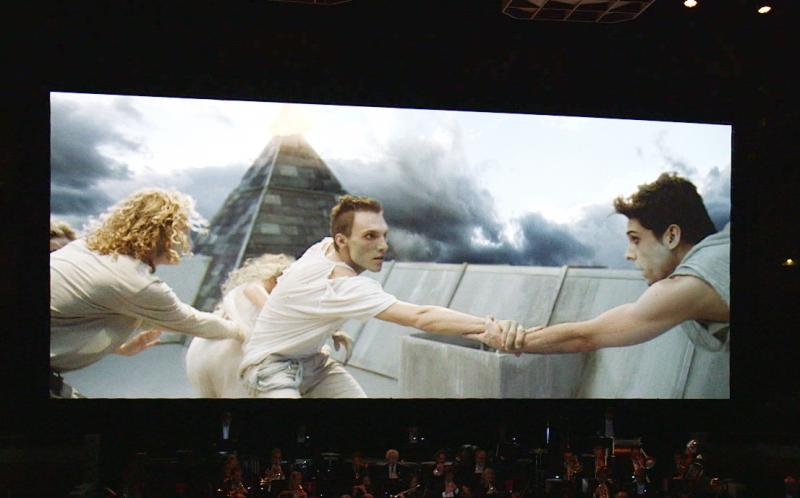

So does this new kind of Gesamtkunstwerk (a synthesis of the arts) work? In some ways it’s akin to Matthew Bourne’s re-imaginings of classical ballets, inventing new storylines while acknowledging the themes and symbols of the original scenarios. In van Woerkum’s film of The Firebird you have a strange world and a handsome chap seeking a beautiful woman, some golden apples, and a girl who sprouts feathers; in Daphnis et Chloé there’s a narrative of boy and girl seeking each other and eventually coming together, with a morning breakfast scene (to fit the famous Dawn number) and a "Pan" figure (see picture above).

So does this new kind of Gesamtkunstwerk (a synthesis of the arts) work? In some ways it’s akin to Matthew Bourne’s re-imaginings of classical ballets, inventing new storylines while acknowledging the themes and symbols of the original scenarios. In van Woerkum’s film of The Firebird you have a strange world and a handsome chap seeking a beautiful woman, some golden apples, and a girl who sprouts feathers; in Daphnis et Chloé there’s a narrative of boy and girl seeking each other and eventually coming together, with a morning breakfast scene (to fit the famous Dawn number) and a "Pan" figure (see picture above).

Bourne’s original company name was Adventures in Motion Pictures, pointing to the fact that telling a story in dance is very much like making a silent film. Here, where silent film is what we see alongside the music (controlled to fit its sequence, of course), there are narrative needs very similar to the old silent movies – showing a key object in close-up so the viewer will watch it in future, zooming and cutting to create a sense of movement from place to place, and so on.

Van Woerkum has this all prepared and does it with great skill, although in film there have to be a lot more specific images to tell a story than there would be with a dance production. He stretches the boundaries of narrative film to the extent that you wonder which bits are flashbacks and which are thoughts in the characters’ heads, and in both films there is a clearly choreographed set piece. For example the "Infernal Dance" from The Firebird is accompanied by real dancers, apparently on the roof of the building we already know, with flaming turrets.

It can get a bit clunky and it can be clever-clever, as in the sequence of people falling upstairs in The Firebird, and the Pan girl emerging from water without getting her hair wet in Daphnis et Chloé. But overall the filmic narratives are intriguing, even puzzling, and hold the attention superbly. In a concert hall, where the music is supposed to be put first, is that the object of the exercise? The applause after each performance seemed to be of the polite-admiration kind, rather than enthusiasm for the enhanced musical experience. After all, the musicians were hidden in darkness, so their role became one of accompaniment as far as the audience was concerned, for all the high intentions of the concept.

It can get a bit clunky and it can be clever-clever, as in the sequence of people falling upstairs in The Firebird, and the Pan girl emerging from water without getting her hair wet in Daphnis et Chloé. But overall the filmic narratives are intriguing, even puzzling, and hold the attention superbly. In a concert hall, where the music is supposed to be put first, is that the object of the exercise? The applause after each performance seemed to be of the polite-admiration kind, rather than enthusiasm for the enhanced musical experience. After all, the musicians were hidden in darkness, so their role became one of accompaniment as far as the audience was concerned, for all the high intentions of the concept.

But the BBC Philharmonic played the scores as if inspired, and no doubt they were by their principal guest conductor, while leader Yuri Torchinsky and the wind principals contributed eloquent solos. The opulent sound and vigorous life Ben Gernon (pictured above) brought to both these readings was in truth very splendid, and the "Danse générale" made a mighty impact at the end.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment