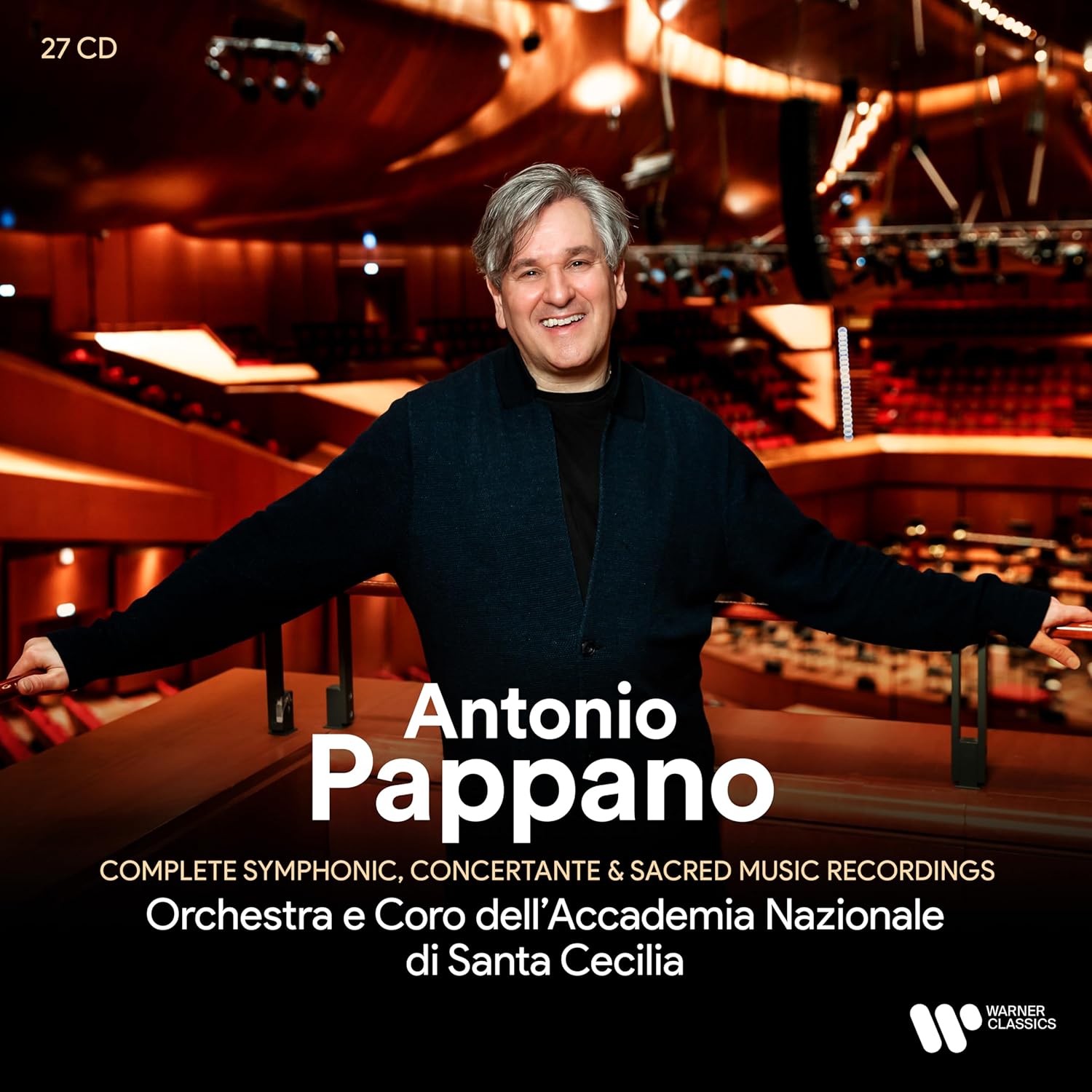

Antonio Pappano: Complete Symphonic, Concertante and Sacred Music Recordings Orchestra e Coro dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia (Warner Classics)

Antonio Pappano: Complete Symphonic, Concertante and Sacred Music Recordings Orchestra e Coro dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia (Warner Classics)

Exploring this compendious 27 CD box set has been a lot of fun. Rome’s Santa Cecilia Orchestra began life in 1908, "the first orchestra in Italy to devote itself exclusively to the symphonic repertoire”. The group has enjoyed a much higher international profile in the last few decades, much of the credit due to Antonio Pappano, the orchestra’s Music Director from 2005 to 2023. We get 27 discs here containing an impressively broad range of repertoire, a common thread being Pappano’s big-hearted, emotionally generous conducting. He’s unafraid to let the brass and winds really sing out, and the strings have plenty of heft. Try a recently released disc containing Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade, full of characterful wind solos, raucous brass and an idiomatic turn by orchestral leader Carlo Maria Parazzoli, along with two ‘original’ versions of Mussorgsky’s Night on Bald Mountain, one with choir. Pappano is excellent in Russian repertoire: his Rome recording of Rachmaninov’s Symphony No. 2 is one of my favourites, and Tchaikovsky’s last three symphonies are full of colour and punch. And Beatrice Rana playing Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1, coupled with a deliriously dark performance of Prokofiev’s second concerto. Rana is also excellent in Strauss’s quirky Burleske, coupled with Pappano's very humane reading of Ein Heldenleben. Respighi’s three Roman tone poems are a mixed bag here; Fontane di Roma’s quiet, evocative corners far more affecting than the noisier moments in the other two. Pappano’s Mahler 6 is one of the great ones, though – brilliantly paced, razor-sharp (replete with seismic hammer blows) and very moving. I also enjoyed a previously unreleased 2019 recording of Bruckner 8 which boasts some gorgeous italianate strings in the long slow movement.

It’s good to become reacquainted with a pair of discs containing Bernstein’s three symphonies. I’m still not convinced that they’re the composer’s best work, but these performances are as viscerally exciting as any available (try No. 1’s insane “Profanation”). Beatrice Rana (again) is terrific in The Age of Anxiety and Pappano’s version of Symphony No. 3 features Josephine Barstow in the speaking role. A pin-sharp, exhilarating account of the Prelude, Fugue and Riffs is a fun coupling, with a stellar turn from clarinettist Alessandro Carbonare. There’s Dvořák’s 9th Symphony, Saint-Saëns’ 3rd Symphony and a Carnaval des animaux with Pappano and Martha Argerich on pianos – all in good, solid performances. You’d expect a selection of Rossini overtures from these forces to sound idiomatic, and their version of William Tell is a blast. Disc 26, Cinema, takes us into cheesier crossover territory, pianist Alexandre Tharaud tackling a bewildering range of film themes. While it’s great to hear Michel Legrand’s pastiche concerto from Les Demoiselles de Rochefort played this well, one wonders who on earth thought it was a good idea to include an extract from Francis Lai’s score to the soft-core sleazefest Emmanuelle 2?

The big choral works are impressive; you’d expect an opera specialist to be good at marshalling huge forces. Pappano’s recent Proms performance of Britten’s War Requiem drew praise from Boyd Tonkin, and his live 2013 recording starring Anna Netrebko, Ian Bostridge and Thomas Hampson is among the best modern recordings. The Santa Cecilia chorus give Britten’s “Dies Irae” Verdian weight, and the “Sanctus” explodes into life. There’s a 2009 live recording of the Verdi Requiem with a sterling turn from bass René Pape, and a moving account of Verdi’s Four Sacred Pieces. I wish we’d had the original piano-and-harmonium version of Rossini’s Petite messe solennelle instead of the composer’s orchestral rewrite, but this version has decent soloists and makes a good case for the work. To sum up, almost everything here is good, and much of it is great. That many of the recordings are live adds to the fun, the odd cough and audible intake of breath never getting in the way. Recommended.

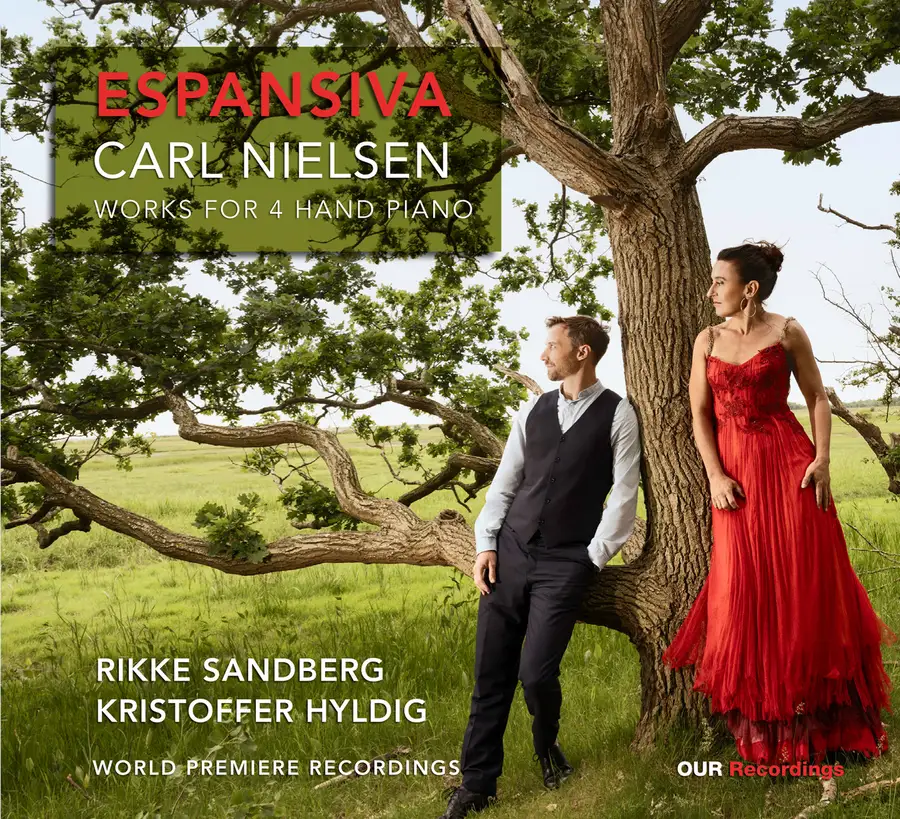

Nielsen: Espansiva – works for 4 hand piano Rikke Sandberg, Kristoffer Hyldig (OUR Recordings)

Nielsen: Espansiva – works for 4 hand piano Rikke Sandberg, Kristoffer Hyldig (OUR Recordings)

Hearing big orchestral works transcribed for piano is a reminder that keyboard arrangements were, for centuries, the easiest way for audiences to get to know new pieces. And useful for composers too: Carl Nielsen made this piano duet transcription of his Sinfonia Espansiva so that he could promote the symphony to conductors, publishers and colleagues. It worked – Nielsen signed a contract with Leipzig’s C.F. Kahnt in 1913 to print the orchestral score, and the four-hand piano version was included in the catalogue. Mysteriously, it never materialised. Until Danish pianist Rikke Sandberg heard about the transcription and managed to track down the manuscript in Copenhagen’s Royal Library. Sandberg and duet-partner Kristoffer Hyldig have tinkered with the score (“…we have taken certain liberties…”) but rightly argue that any minor alterations sympathetic to Nielsen’s intentions. They also use two pianos, a Steinway and a Fazioli, meaning that both players can pedal individually, each instrument’s character suited to the register deployed. The results are spectacular, both in terms of performance and engineering, Nielsen described the symphony’s first movement as “a gust of energy and life affirmation blown out into the wide world”, and we really sense that here. The pounding unison A’s which open the work are thrilling; rarely has this music sounded more dance-like, an affirmative counterblast to the nihilism of Ravel’s La Valse. Listen to how Sandberg and Hyldig ease into the loopy waltz just before the six-minute mark, and how they build the tension before the movement’s assertive close.

Nielsen’s “Andante pastorale” becomes more intimate and personal here, the unison string writing balder on two pianos. At the movement’s close we lose the wordless vocals but the twinkling, gamelan-like coda is magical, Nielsen achieving miracles over a sustained E flat chord. The third movement’s witty counterpoint is crisp and sharp, and the finale’s unpretentious hymn tune sings out, the tempo here ideal. We get three couplings: two extracts from Nielsen’s opera Saul and David arranged by the composer, and the jaunty Højby Rifle Club March, originally composed by Nielsen’s father Niels Jørgensen. It’s heard here in an edition partially arranged by the composer’s son and completed by Hyldig. A life-affirming release, brilliantly played. OUR label co-founder Lars Hannibal rightly points out that we need this music in these dark times, Nielsen capable of exuding “a sense of optimism all too rare for us denizens of the 21st century.” He’s right. Buy, download or stream this disc forthwith and the world will seem a brighter place.

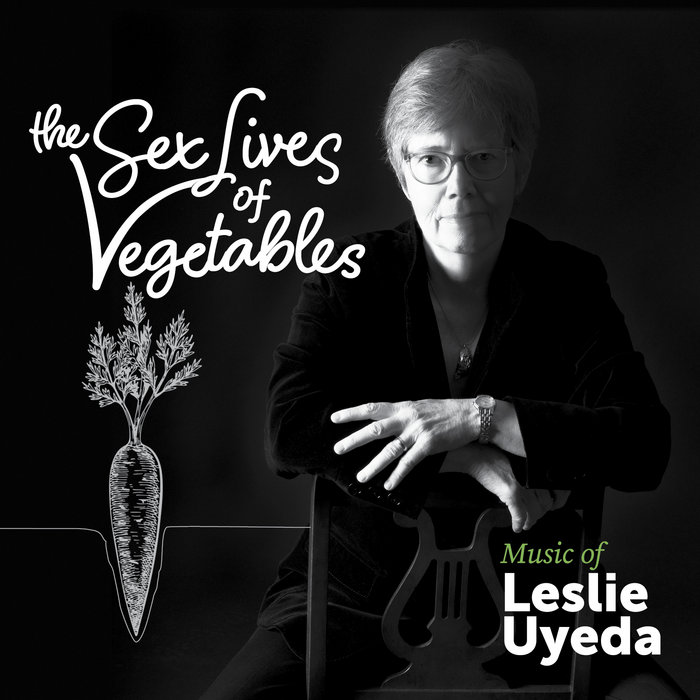

Leslie Uyeda: The Sex Lives of Vegetables Heather Pawsey (soprano), Rachel Kiyo Iwaasa (piano), AK Coope (clarinet) (Redshift Records)

Leslie Uyeda: The Sex Lives of Vegetables Heather Pawsey (soprano), Rachel Kiyo Iwaasa (piano), AK Coope (clarinet) (Redshift Records)

This album’s intriguing and suggestive title persuaded me to listen to what turned out to be a striking and quirky pair of song cycles by Canadian composer Leslie Uyeda. I came for the title, but stayed for an enjoyable recital of the music of a composer I didn’t previously know. The two cycles – The First Woman and The Sex Lives of Vegetables, both to words by Lorna Crozier – are separated by an 8-minute piano solo, written for pianist Rachel Kiyo Iwaasa in memory of her mother, touchingly played by Iwaasa. Uyeda has set Crozier’s words in over 50 songs, and we get 19 here. As ever with listening to song on record (without the visual cues of a live performance) the words are hard to discern without the help of the booklet. On reading, the texts of The First Woman are bold and direct, which is true also of Uyeda’s musical interpretation, the vocal lines angular and the piano part ranging freely over the whole keyboard. It is as much dramatic scena as song cycle – the piano part would orchestrate very easily. The music though offers no comforting resolution to the tough questions of the libretto.

The main event is the 15-song title sequence, miniatures mostly 1-2 minutes long, to texts that, as the name suggests, sexualise vegetables. These range from the romantic (“Artichokes… want seduction, melted butter”) to the frank and unblinking (the opening song, “Carrots”, begins with the line “Carrots are f***ing the earth” and goes from there). The texts are fun, and Uyeda responds in kind, the addition of AK Coope’s clarinet giving an extra voice in the discourse. Here the text is clearer, sometimes declaimed rather than sung, and there’s more than a hint of Judith Weir’s early vocal works, in the rapid switches of tone, and in the musical allusions below, and sometimes, on the surface (Façade would be another point of reference). Pawsey is by turns cheeky, earnest, stern, seductive (in “Onions”, for example), wry (in “Peas”) and languorous (in “Scarlet Runner Beans”, aided by the clarinet), clearly enjoying herself. Bernard Hughes

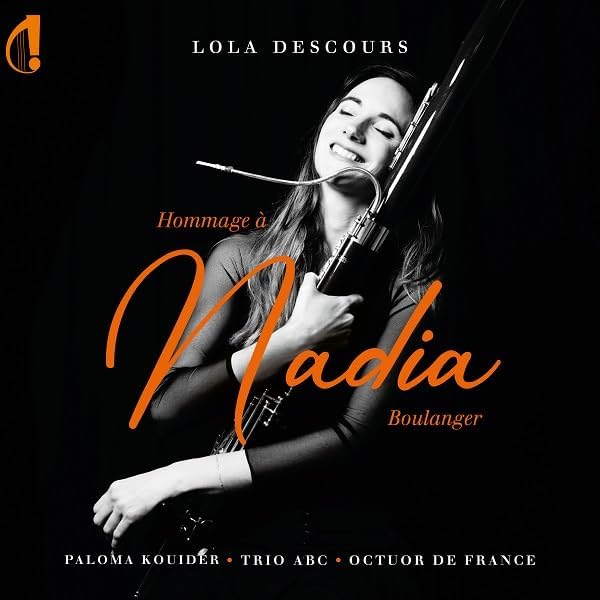

Hommage à Nadia Boulanger Lola Descours (bassoon) (Indesens Calliope)

Hommage à Nadia Boulanger Lola Descours (bassoon) (Indesens Calliope)

If anniversary tributes can sometimes seem like sombre box-ticking exercises, this one isn’t. Lola Descours’ Hommage à Nadia Boulanger is personal, idiosyncratic and, above all, fun. Descours has assembled a tremendous and varied programme themed around the huge range of composers with some kind of link to Nadia Boulanger, and there isn’t a weak track. Her main partnership is with pianist Paloma Kouider who (for me at least) has been a real discovery. In their partnership they certainly know how to play with all the elegance, grace and demureness that might be expected of them at a smart Paris ‘salon’ (try the slower movements of the Saint-Saens sonata), but more often they seem to spark off in each other a real vein of energy and feistiness which produces strongly characterful playing, as in the “Toccata” from Stravinsky’s Suite Italienne. Nothing here ever sounds insipid: Philip Glass’s “Love Divided By:IV” has wonderful – even surprising – ebb and flow.

Descours has also teamed up with one of Paris’s top young orchestral double bassists Ulysse Vigreux and accordion phenomenon Élodie Soulard to form Trio ABC, and this group bring real contrast on the two tracks they are involved in. They are heard in a gorgeous Piazzola’s “Maria de Buenos Aires” and also in a lively, specially commissioned piece from Vladimir Cosma (not the Hungarian-born “Autumn Leaves” tunesmith but the Romanian-born composer of over 300 film and TV scores). Descours is making her mark. She was already playing with the Orchestre de Paris at the age of 19, and is now principal at the Rotterdam Philharmonic. And my incorrigibly pointless trivia brain is trying to work out if the impressive Paloma Kouider’s ‘classes preparatoires’ in literature at Lycée Louis-le-Grand (she effortlessly quotes Sartre’s theories of personal responsibility at interviewers) was at the same time as France’s leading current candidate for Prime Minister, Lucie Castets. Sebastian Scotney

Angele Dei Latvian Radio Choir/Sigvards Kļava (Skani)

Angele Dei Latvian Radio Choir/Sigvards Kļava (Skani)

Last year I reviewed the Latvian Radio Choir and Sigvards Kļava’s award-winning disc of choral music by John Cage. I hadn’t known what to expect – but it was a revelation and deserved its acclaim. With this new album they are back on home turf, singing music by Baltic composers, some known to me and some not, all the pieces in premiere recordings. The best known is Pēteris Vasks, who has two tracks: the stunningly poised and luminous Angele Dei which opens proceedings, sung with wondrously long-breathed phrases, and the somewhat less memorable Actus Caritatis. They are both in Vasks’ familiar rich tonal style, and his spiritual, contemplative mode is found in several of the pieces, even where their musical language leans more to the avant-garde.

More sonically adventurous than the Vasks is Krists Auznieks’ Sensus, a large-scale piece with rich chromatic harmony, glissandos and other effects, solo voices emerging from the chordal texture to sing phrases from St Paul. It is very striking, and virtuosically sung. Where these other tracks are predominantly about harmony, Ruta Paidere’s Magnificat focuses on melody. But not conventional western melody, rather incantatory lines that embrace Jewish synagogue chant in a dense polyphonic web.

As with Vasks, there are two pieces by Andris Dzenitis. Om, Lux Aeterna from 2012 combines echoes of Russian Orthodox church music with the strangeness of John Cage, the gravelly low basses really excelling, while Prayer is a simple, humble hymn in which time stands still. As it does in Mārtiņš Viļums’ The Fate of King Lear’s Children, an example of the technique he dubs “microsonorism”. It is peculiar, spacious like the Vasks but much more unsettling, archaic and monumental, dramatic in an unshowy way. Conductor Sigvards Kļava wants this album to mark the state of Latvian music today. It does this not only in terms of the range of composers represented, but also in the quality of the choral singing by a national choir the nation can be proud of. Bernard Hughes

Dalia's Mixtape BBC Symphony Orchestra/Dalia Stasevska (Platoon)

Dalia's Mixtape BBC Symphony Orchestra/Dalia Stasevska (Platoon)

My one disappointment with this release is that it’s a virtual mixtape, one assembled without the compiler worrying about C90 cassette side lengths and having to find a pen with a nib fine enough to write down the track details on a small piece of card. The compiler here is conductor Dalia Stasevska, whose career I’ve followed since hearing her conduct the Orchestra of Opera North back in 2018. In her words, the album presents ten contemporary works from an unusually diverse range of composers, “pieces that broaden our understanding of what a large group of acoustic instruments can do.” Listen to this as you would a cassette: the tracks have been ordered by Stasevska and make sense as a huge sequence. Anna Meredith’s Nautilus (heard here in Jack Ross’s orchestral transcription) makes for an arresting opener. This propulsive fanfare is as physically exciting as it’s unnerving, the superficial glitter undercut by menacing low brass. Swedish composer Andrea Tarrodi’s Wildwood unfolds like a vast single-movement symphony, complete with very Sibelian string ostinato. Most arresting is the central section, an eerie reverie with prominent harp and icy string lines. Judith Weir’s deliberately ambient Still, glowing is a contrast, seven minutes of sustained, amorphous string chords. Not much happens, but it’s delivered by the BBC Symphony Orchestra with fierce intensity.

A useful, well-designed booklet comes with this release, though I’d also recommend dipping into a series of short podcast conversations between Stasevska and Andrew Mellor, one for each track on the album. Especially useful is the episode featuring Julius Eastman’s Symphony No. 2. Composed in 1983 and subtitled The Faithful Friend: The Lover Friend’s Love for The Beloved, this painful, intense piece feels much bigger than it actually is. Eastman deserves this sort of advocacy, and Stasevska’s charisma and intent make the music speak.

Caroline Shaw’s The Observatory has us gazing at the night sky from the Griffin Observatory in Los Angeles, overhearing snippets of late-romantic orchestral music from the Hollywood Bowl down below. Lauri Porra’s Utu is an elusive depiction of a rural Finnish sunset observed from the composer’s wood cabin, followed, mischievously, by music full of smoke and fog: the late Johan Johansson’s They Being Dead Yet Speaketh extracted from his film score The Miners’ Hymns. Coexistence, by SØS Gunver Ryberg, is ten minutes of dissonant growls and snarls, the orchestra augmented with electronics. After which, Swaddling Silk and Gossamer Rain by Noriko Koide offers some relief, a silkworm’s brief life depicted in music which skitters, scuttles and wriggles about before fading away. Julia Wolfe’s large-scale Pretty is a thrilling closer, “a raucous celebration – embracing the grit of fiddling, the relentlessness of work rhythms, and inspired by the distortion and reverberation of rock and roll”. There are passages where you can’t believe that the sounds aren’t being manipulated, 90 acoustic instruments pushed to the limit. An enthralling compilation, superbly played and very well recorded. Please can we have a physical release, ideally as a gatefold double LP?

Add comment