JS Bach: Magnificat, CPE Bach: Magnificat Gaechinger Cantorey/Hans-Christoph Rademann (Accentus Music)

JS Bach: Magnificat, CPE Bach: Magnificat Gaechinger Cantorey/Hans-Christoph Rademann (Accentus Music)

Coupling this pair of Magnificat settings on a single CD makes so much sense. JS Bach’s 1723 Magnificat is wonderfully served here, Hans-Christoph Rademann’s Gaechinger Cantorey turning in a performance which marries lyricism with rhythmic zest. Rademann’s 19-voice choir make a thrilling sound at full pelt (listen to them in the “Fecit potentiam”) and there’s some exquisite orchestral playing from recorders and natural trumpets. Solo voices, drawn from the chorus, are exceptionally good: sample the little trio “Suscepit Israel” near the close and weep. Bach’s closing chorus is terrific here, trumpets and drums blazing.

From here to the nine-movement Magnificat written in 1749 by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (and also in D major) is quite a step, this work opening with a thrilling, propulsive burst of energy. The musical language contains a few nods to JS Bach, notably in the concluding chorus’s fugal writing, but fans of the younger composer’s spiky orchestral and keyboard music won’t be disappointed. CPE’s boldness and wit are irresistible, particularly in numbers like the “Et misericordia” chorus, the sinuous vocal lines and harmonic quirkiness striking. Or in the bounce and bluster of the “Fecit potentiam” aria which follows it, bass Markus Eiche revelling in the florid solo line. Well recorded and nicely packaged – a keeper.

Heinz Holliger – Lunea (ECM)

Heinz Holliger – Lunea (ECM)

Bring on the complexity. It starts with an anagram and a double-meaning, just in the title. Heinz Holliger’s Lunea” – Lenau-Szenen in 23 Lebensblättern was performed in a premiere run the Zurich Opera House in March 2018, and this is a live recording from those performances. Lunea (moon) is an anagram of Lenau (the romantic poet). There is also a play on the double meaning of the German word Blätter – to mean both leaves and pages. These are the first signals that nothing here is going to be simple, or indeed can or should be taken at face value.

Holliger's triple career as oboist, conductor and composer is remarkable, His formative composition studies were in his early 20s in Basel with Boulez, so the expectation that music should be challenging and multi-layered and always make extreme demands on the listener is ingrained, and has now been with him for six decades. "My entire relationship with music is such that I always try to reach its limits," he has said. Indeed.

One reviewer of the opera premiere described the work as a “stream of sound which always stays in motion”. The opera is an extended, 100-minute work, based on an earlier, half-hour song cycle which exists in versions with piano and chamber ensemble. There isn’t any kind of linear plot. The poet Nikolaus Lenau finds himself doubled-up as a character with his brother-in-law who also happens to have been his biographer, Anton Xaver Schurz, both characters interpreted (either separately or simultaneously) by the greatest German Lieder singer of our time, Christian Gerhaher. The very great Gerhaher is joined by a top-flight cast including Juliane Banse. Also consistently excellent are the 12 singers of the Basler Madrigalsolisten. Holliger’s choral writing is often based on devilishly complex and shifting tone-clusters, and they deliver them superbly.

The listener is left with the choice with a work like Lunea. Does one try to wrestle with the themes, such as mental illness and the romantic soul, parallels between romanticism and post-expressionism; does one attempt to unravel some of the puzzles the work presents? Once one finds that post-Bergian numerology and mirror-writing in the libretto have been thrown into the mix, it all starts to look like a never-ending and possibly fruitless task. Or does one just abandon all that and merely listen with pleasure to a constantly-shifting world of sound and emotion as conveyed by some excellent performers? It is an awful lot easier. - Sebastian Scotney

Kurt Leimer: Piano Concerto No. 3, Strauss: Panathenäenzug Gilles Vonsattel (piano), Berner Symphonieorchester/Mario Venzago (Schweizer Fonogramm)

Kurt Leimer: Piano Concerto No. 3, Strauss: Panathenäenzug Gilles Vonsattel (piano), Berner Symphonieorchester/Mario Venzago (Schweizer Fonogramm)

Joseph Lauber: Symphonies 3 and 6 Sinfonie Orchester Biel Solothurn/Kaspar Zehnder (Schweizer Fonogramm)

Two choice releases from Schweizer Fonogramm have provided much-needed distraction in recent months. You know you’ll like these discs before you’ve listened to a note; production values are stellar, with appealing art design, impressive engineering and sleeve notes which can be read comfortably without recourse to a magnifying glass. Kurt Leimer’s Piano Concerto No. 3, premiered in 1953, is a rarity, a 20th century concertante work for piano (left-hand) which wasn’t commissioned by the famously prickly Paul Wittgenstein. Leimer (1920-1974) was a child prodigy whose talents as a pianist were lauded by Furtwangler and Gieseking. He was conscripted in 1944 and pitched up in an Italian prison camp, where a fellow and conscript and pianist’s physical and psychic injuries inspired this concerto. It’s an engaging piece, a dizzying blend of late romanticism and Gershwin-era jazz, brilliantly scored. Perhaps it’s a tad overlong, but the choice moments come thick and fast. Guilles Vonsattel’s performance here is superb. He follows the Leimer with Strauss’s similarly rare Panathenäenzug, a Wittgenstein commission described as a ‘symphonic etude in the form of a passacaglia”. Strauss’s eight-bar bass line is repeated 48 times, the foundation for an increasingly outlandish set of variations. Twenty-four repetitions would have suited me better, but this performance is a lot of fun, especially when Mario Venzago’s Berner Symphonieorchester lets rip. Wittgenstein performed the work just once, in 1928. Leimer met the composer in his final years, his playing of the Panathenäenzug so impressing Strauss that he granted him exclusive performing rights.

There’s also a second volume of symphonies by the Swiss composer Joseph Lauber. His breezy Symphony No. 3 dates from 1895, its audible influences including Schubert, Dvorak and Bruckner. Entertaining (check out the slow movement’s lower string line) but I prefer No. 6, completed a year before Lauber’s death in 1952. The leaner scoring is immediately striking, this recording’s conductor Kaspar Zehnder rightly describing the work as neo-classical in the booklet interview. Zehnder’s Sinfonie Orchester Biel Solothurn are persuasive, particularly in the finale’s treacherous high string writing. There’s a fun coupling in the form of Lauber’s three-movement symphonic suite Die Alpen. It’s gorgeous, a small-scale cousin to Strauss’s Alpine Symphony which opens with mountaintop horn calls looking ahead to those in Mahler 7. The last movement includes a brassy 4/4 rendition of the Swiss national hymn “Rufst Du mein Vaterland”, which will sound familiar to UK listeners. Both discs are worth exploring. Buy the pair.

There’s also a second volume of symphonies by the Swiss composer Joseph Lauber. His breezy Symphony No. 3 dates from 1895, its audible influences including Schubert, Dvorak and Bruckner. Entertaining (check out the slow movement’s lower string line) but I prefer No. 6, completed a year before Lauber’s death in 1952. The leaner scoring is immediately striking, this recording’s conductor Kaspar Zehnder rightly describing the work as neo-classical in the booklet interview. Zehnder’s Sinfonie Orchester Biel Solothurn are persuasive, particularly in the finale’s treacherous high string writing. There’s a fun coupling in the form of Lauber’s three-movement symphonic suite Die Alpen. It’s gorgeous, a small-scale cousin to Strauss’s Alpine Symphony which opens with mountaintop horn calls looking ahead to those in Mahler 7. The last movement includes a brassy 4/4 rendition of the Swiss national hymn “Rufst Du mein Vaterland”, which will sound familiar to UK listeners. Both discs are worth exploring. Buy the pair.

O Jerusalem! Apollo's Fire/Jeanette Sorrell (Avie)

O Jerusalem! Apollo's Fire/Jeanette Sorrell (Avie)

Listening to O Jerusalem!, billed as “a harmonious meeting of religions, cultures and people in the Holy City”, is as much a worthwhile educational experience as a musical one. Jeanette Sorrell’s latest concept album is an exuberant, uplifting examination of sacred and secular music drawn from the city’s Jewish, Arab, Armenian and Christian quarters. Her booklet notes are a good read, putting Jerusalem’s history and geography into context. There’s even a handy map, an introduction to Sorrell’s five-day city tour. Baritone Jeffrey Strauss opens proceedings with “Ir me kero, madre, a Yerushalayim”, an incantatory welcome, followed by an exuberant Sephardic folk song. The mixture of popular and serious material is brilliantly judged, and there’s a wonderful sequence of instrumental numbers representing the Arab and Armenian areas.

Day Four’s "Mosque, Cathedral and Synagogue" incorporates plainchant, a Muslim call to prayer and an excerpt from Monteverdi’s Vespers, the musical connections made disarmingly clear. Day Five’s multi-faith shindig contains the most joyous music I’ve heard all month, closing with a medieval Spanish number, “Santa Maria, Strela do Dia”. We can never know what these songs would have originally sounded like, but Sorrell’s arrangements feel authentic and the performances, recorded in concert, crackle with life. Ouds, dulcimers and qanuds ring out, and the choral singing has plenty of oomph. A marvellous disc.

Now the green blade riseth – Choral Music for Easter The Choir of King’s College, Cambridge/Daniel Hyde (King’s College, Cambridge)

Now the green blade riseth – Choral Music for Easter The Choir of King’s College, Cambridge/Daniel Hyde (King’s College, Cambridge)

Listen to this disc in sequence and you get the entire Easter story in choral form. The mixture of musical styles works well. It’s as if different sections are told by different voices, with four traditional hymns prefacing each stage. George Malcolm’s “Ingrediente Domino”, prefaced here by a colourful organ fanfare, is one of several numbers alluding to Gregorian plainchant. Duruflé’s “Ubi caritas et amor” is another, barely rising above a whisper; the depth of sound this choir makes, even at low volume, is remarkable. Familiar hymns like “There is a green hill far away” don’t disappoint. Though I found myself replaying the rarities; Rossini’s “O salutaris Hostia” is an exquisite late miniature, Daniel Hyde’s Choir of King’s College making the most of the abrupt change in dynamics in the third line, proof that Rossini’s theatrical instincts hadn’t left him. Antonio Lotti’s little six-part “Crucifixus” is another jewel, sung with rare sincerity.

Bob Chilcott’s setting of the traditional French “Now the green blade riseth” is a serene delight, Chilcott decorating the organ accompaniment with avian tweets and chirps. Elgar’s “The Light of Life” pops up near the close, the disc finishing with an extended keyboard improvisation by Tournemire, transcribed by Duruflé. If you’re fond of the English choral tradition, you need to hear this; the performances have a winning freshness and are beautifully recorded. Good notes are thrown in, along with texts and translations.

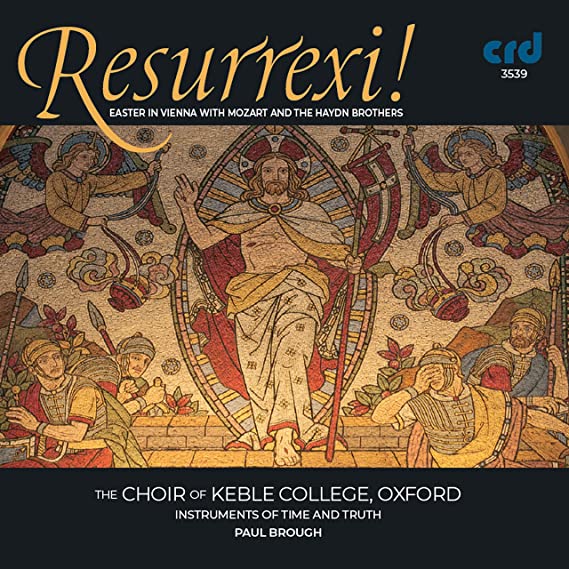

Resurrexi! – Easter in Vienna with Mozart and the Haydn brothers Choir of Keble College, Oxford, Instruments of Time and Truth/Paul Brough (CRD)

Resurrexi! – Easter in Vienna with Mozart and the Haydn brothers Choir of Keble College, Oxford, Instruments of Time and Truth/Paul Brough (CRD)

This is fun, a speculative mass sequence assembled by Paul Brough with Mozart’s compact KV258 Spaurmess at its centre, the movements intermingled with snatches of plainchant and two sacred works by brothers Josef and Michael Haydn. Mozart’s patron, the Archbishop of Salzburg, stipulated that the whole Missa Solemnis should last around 45 minutes. Brough’s disc lasts 56 minutes, but you suspect that the Archbishop would have forgiven him. Baritone Graham Kirk has a starring role as Cantor, especially impressive in the long chant following Mozart’s “Gloria”, and the Keble College Choir make a lively, full-bodied sound. Brough stresses the exuberance of Mozart’s mass setting, his “Kyrie” full of momentum and the tiny “Sanctus” unfolding as if in a single breath.

There’s also Mozart’s florid, effervescent Regina Coeli, and a winning performance of the KV274 Church Sonata, Benjamin Mills’ chamber organ beautifully matched with the upper strings. Michael Haydn’s Victimae paschali laudes pops up halfway through, so sweetly done that you’re immediately tempted to hit the replay button. The C major Te Deum by Joseph Haydn makes for an upbeat finale. There’s lively, idiomatic backing from Oxford-based Instruments of Time and Truth, and an appealing bloom to the recorded sound. And good to learn that the CRD label is still a going concern.

Add comment