Debussy: Piano Works Volume 2 Dennis Lee (piano) (ICSM Records)

Debussy: Piano Works Volume 2 Dennis Lee (piano) (ICSM Records)

I’m a huge fan of Colin Matthews’ idiomatic orchestral transcriptions of Debussy’s Préludes, so much so that it’s been a good few years since I’ve listened to the piano originals. This disc caught me unawares and made me reflect on just how difficult this music is to bring off. Bringing out every detail can impede the music’s flow, while concentrating too much on colour and atmosphere can make everything sound a bit blurry and vague. This is Malaysian pianist Dennis Lee’s second Debussy collection, and it’s something special. Try his “Voiles” from Book 1. It’s deliciously unsettling, Lee subtly highlighting the music’s strangeness. “Ce qu'a vu le vent d'ouest”, a dark Lizstian display piece, is terrifying here, one of the most visceral storm descriptions in music. It’s surrounded by a pair of technically much simpler numbers: “Des pas sur la neige” is impressively bleak, the understatement perfectly judged. “La fille aux cheveux de lin” is exquisite, Lee barely audible at the close.

Book 2 is equally enjoyable, Lee nailing General Lavine’s lopsided gait and “Feuilles mortes” suitably bleak. “Hommage à S. Pickwick Esq.” sounds as if it’s being written on the hoof, “Canope” peaceful and otherworldly. There’s a jazzy flexibility to Lee’s “Les tierces alternées” and Feux d'artifice” is dizzying. A lovely disc, beautifully recorded.

Mozart: String Quintets K.515 & K. 516 Quatuor Ébène with Antoine Tamestit (viola) (Erato)

Mozart: String Quintets K.515 & K. 516 Quatuor Ébène with Antoine Tamestit (viola) (Erato)

This is hyper-alive quintet playing, with a fabulously thoughtful and thought-through approach to ensemble, balance and pacing. And the collaboration with Antoine Tamestit is seamless. The story of how this musical friendship came about is well told in the booklet: it was the coincidence of the German ARD's quartet competition and the viola competition happening in the same year (2004)... and the fact that the winners of both were French (and the flautist too) which brought about this happy encounter. The Ébènes instantly saw Tamestit as a kindred spirit in 2004, and it is clear that they still do. The programme note also has a nice reflection on the rightness of the pairing of C major and and G minor quintets, and how it creates a good balance of opposing and complementary works... as it does with Mozart's last two symphonies.

The G minor quintet brings out the most questionable (to me) and then the best aspects of these performances. I find it impossible to get accustomed at all to the violent, short, stabbing way they attack the forte chords in the fourth and sixth full bars in the minuet. I find it over-bearing, and start to wonder if the fact that the group made this recording (early in the pandemic in June 2020) in the 1150-seater Auditorium Patrick-Devedjian at the Seine Musicale on the Île Seguin might explain why they take this very weighty, portentous approach to the music, as if feeling the need to semaphore details which might not get heard . Following that, their intense yet gentle way with the slow movement works much better. It has great poise and rightness about it, and an unflagging and painstaking approach to every detail. Sebastian Scotney

Rachmaninov: All-Night Vigil Choir of King’s College, London/Joseph Fort (Delphian), Clarion Choir/Steven Fox Pentatone

Rachmaninov: All-Night Vigil Choir of King’s College, London/Joseph Fort (Delphian), Clarion Choir/Steven Fox Pentatone

Rachmaninov’s All-Night Vigil of 1915 (he wrote it in two weeks flat) is arguably “the quintessential product of the cultural ferment of Imperial Russia” and yet remains an unfamiliar aspect of Rachmaninov’s output, certainly in comparison with the concertos and symphonies. It has a very different feel from those virtuosic, often extrovert works: its predominant tone is one of humble prostration, using a mixture of directly borrowed Russian orthodox chants and Rachmaninov’s imitation of the style. These two new recordings are both welcome additions to the catalogue, albeit coming at the music from different angles.

The King’s College Choir opens with a bright sound which gradually darkens as the movements proceed. Caitlin Goereing’s alto solo in “Blagoslovi, dushe moya, Gospoda” is dolorous and coloured with bell-like resonance in the upper voices. The choir, made up of students at King’s, was been augmented for this recording by some alumni and some guest singers. They really help beef up the bottom end, which is so important in this music. The performance has a prayerful stillness and supplication. For a choir that habitually performs Anglican church music there is a British politeness about the sound that only occasionally breaks out into passionate outburst, such as the final “Vzbrannoy voyevode”, blowing away the prevailing meditative mood. Conductor Joseph Fort ensures the homophonic textures are always nicely weighted and the Delphian sound is as good as ever (the recording venue, All Hallow’s, Gospel Oak in London, has such a beautiful acoustic for this kind of repertoire).

Right from the start, the Clarion Choir explores the depths of the basso profundo of Glenn Miller, whose fruity “Opening Exclamation” is arresting and delightful. This version has a lower centre of gravity than the KCL, and slightly more rough-edged abandon. There are several standout moments: “Nyne otpushchayeshi” starts with a unison hymn and opens out into an exquisite, ecstatic tenor solo by John Ramseyer and a full-throated choral outburst, and “Blagosloven yesi, Gospodi” builds a rhythmic urgency that starts out in the lower voices before spreading upwards. I hadn’t come across Clarion before – they are a professional chamber choir based in New York, led by Steven Fox – but I certainly want to hear more. The diction and pronunciation sounds terrific (I am not a Russian speaker) and the quality of the singing is top end. The KCL disc benefits from an excellent, detailed sleeve note by historian Rebecca Mitchell, which puts the music in the context of its time, particularly the aesthetic questions of music as entertainment versus its liturgical function. The Clarion Choir’s equally well-presented booklet has, by contrast, a personal account by Fox of his student stay in St Petersburg in 1998, where he fell in love with the All-Night Vigil, which adds a personal aspect to the project. Bernard Hughes

Right from the start, the Clarion Choir explores the depths of the basso profundo of Glenn Miller, whose fruity “Opening Exclamation” is arresting and delightful. This version has a lower centre of gravity than the KCL, and slightly more rough-edged abandon. There are several standout moments: “Nyne otpushchayeshi” starts with a unison hymn and opens out into an exquisite, ecstatic tenor solo by John Ramseyer and a full-throated choral outburst, and “Blagosloven yesi, Gospodi” builds a rhythmic urgency that starts out in the lower voices before spreading upwards. I hadn’t come across Clarion before – they are a professional chamber choir based in New York, led by Steven Fox – but I certainly want to hear more. The diction and pronunciation sounds terrific (I am not a Russian speaker) and the quality of the singing is top end. The KCL disc benefits from an excellent, detailed sleeve note by historian Rebecca Mitchell, which puts the music in the context of its time, particularly the aesthetic questions of music as entertainment versus its liturgical function. The Clarion Choir’s equally well-presented booklet has, by contrast, a personal account by Fox of his student stay in St Petersburg in 1998, where he fell in love with the All-Night Vigil, which adds a personal aspect to the project. Bernard Hughes

Satie: Old Sequins and Ancient Breastplates – Historical Recordings and Rarities 1926-1961 (él Records)

Satie: Old Sequins and Ancient Breastplates – Historical Recordings and Rarities 1926-1961 (él Records)

Stravinsky: Late Music – Sensual Musical Radicalism (él Records)

Cherry Red Records’ él imprint has some gems in its back catalogue, and these two 4-cd sets are well worth acquiring, both packed with well-remastered historical material. The performances in the Satie box are well-chosen, the first disc containing a selection of piano miniatures recorded by the young Aldo Ciccolini in 1956. Much of the fun comes from reading Satie’s bizarre titles and seeing if the music bears any relation to what you hear. I’m fond of “Aperçus désagréables”, played here by Poulenc and Jacques Fevrier, and there’s an enticing selection of solo pieces recorded by Poulenc in 1950. Try the little “Tyrolienne turque” – typically inconsequential, but irresistible. The underrated American pianist William Masselos contributes winning accounts of the Sports et divertissements and the three “Gymnopédies”, taped for RCA in 1959. Oddly, “Vieux sequins et vieilles cuirasses”, isn’t actually included. Satie’s 1895 Messe des pauvres is a fascinating oddity, more a sequence of austere organ solos than a conventional mass setting. There’s loads more: Igor Markevich’s Parade, taped with the Philharmonia in 1954, is fun, and the two-piano arrangement is played by Poulenc and Georges Auric. Satie’s ‘symphonic drama’ Socrate pops up in two versions, and there’s even a spacey 1966 discussion between John Cage and Morton Feldman on the virtues of “music which does not interrupt the noises of the environment.”

Sensual Musical Radicalism offers a generous selection of Stravinsky’s late music. The booklet quotes extensively from Robert Craft’s memoirs, though I’d recommend the second volume of Stephen Walsh’s Stravinsky biography as offering a more nuanced account of the composer’s final years and his belated adoption of twelve-tone techniques. Everything here is worth hearing; the language can be thorny and dissonant but the colours, timbres and rhythms are vintage Stravinsky. The abstract ballet Agon is an ideal starting point, a potent blend of neo-classicism and serialism. Two recordings are included here: Hans Rosbaud gets secure playing from a German radio orchestra in a pioneering 1957 account, but the composer’s own Los Angeles LP is punchier and in better sound. Stravinsky’s career spanned 60 years, and dipping into this set is a reminder of how much of his output has slipped through the cracks. The Flood is a real oddity: think Noyes Fludde without the tunes, an uncompromising ‘biblical drama’ premiered on US television in 1962. Craft conducts, the performance worth hearing for Elsa Lanchester as Noah’s wife and Laurence Harvey narrating. Charles Rosen is a brilliant piano soloist in the elliptical Movements, and we get Craft’s rough-edged but committed premiere recording of the Requiem Canticles, the closing bell sounds chilling. It’s all here: Threni, the Canticum Sacrum, plus the more accessible neoclassical Mass and some excerpts from Stravinsky’s early RCA recording of Orpheus. A fourth disc is subtitled Stravinsky’s Orbit, the selection ranging from Satie to Nono, via Webern and Stockhausen. The remastered sound, even in the older items, is excellent.

Sensual Musical Radicalism offers a generous selection of Stravinsky’s late music. The booklet quotes extensively from Robert Craft’s memoirs, though I’d recommend the second volume of Stephen Walsh’s Stravinsky biography as offering a more nuanced account of the composer’s final years and his belated adoption of twelve-tone techniques. Everything here is worth hearing; the language can be thorny and dissonant but the colours, timbres and rhythms are vintage Stravinsky. The abstract ballet Agon is an ideal starting point, a potent blend of neo-classicism and serialism. Two recordings are included here: Hans Rosbaud gets secure playing from a German radio orchestra in a pioneering 1957 account, but the composer’s own Los Angeles LP is punchier and in better sound. Stravinsky’s career spanned 60 years, and dipping into this set is a reminder of how much of his output has slipped through the cracks. The Flood is a real oddity: think Noyes Fludde without the tunes, an uncompromising ‘biblical drama’ premiered on US television in 1962. Craft conducts, the performance worth hearing for Elsa Lanchester as Noah’s wife and Laurence Harvey narrating. Charles Rosen is a brilliant piano soloist in the elliptical Movements, and we get Craft’s rough-edged but committed premiere recording of the Requiem Canticles, the closing bell sounds chilling. It’s all here: Threni, the Canticum Sacrum, plus the more accessible neoclassical Mass and some excerpts from Stravinsky’s early RCA recording of Orpheus. A fourth disc is subtitled Stravinsky’s Orbit, the selection ranging from Satie to Nono, via Webern and Stockhausen. The remastered sound, even in the older items, is excellent.

Vaughan Williams: Fantasia on the ‘Old 104th’ et al Mark Bebbington (piano), RPO, City of London Chorus/Hilary Davan Wetton (Resonus)

Vaughan Williams: Fantasia on the ‘Old 104th’ et al Mark Bebbington (piano), RPO, City of London Chorus/Hilary Davan Wetton (Resonus)

The latest Vaughan Williams release on Resonus is a mixed bag: The Lark Ascending, of which there are a gazillion recordings, the Piano Quintet of which there are just a few – and the Fantasia (quasi variazione) on the ‘Old 104th’ Psalm Tune, of which this new one is the only currently available. I reviewed a live performance of it at the Barbican in May 2022, by the same forces of pianist Mark Bebbington, with the RPO and the City of London Choir under Hilary Davan Wetton. It had lain unperformed live since its second outing in the Proms of 1950 and my conclusion then was that, although not deserving total neglect, it was far from a lost masterpiece. And while I’m happy to have this very excellent recording available, I’ve not really changed my view. The structure still feels lopsided, with long chunks of solo piano, in which the orchestra and choir sit around not doing much. I can’t fault Bebbington’s playing, nor the commitment of the choir. It’s interesting to hear and definitely one for RVW completists, but won’t win round any agnostics. The last two minutes are great, though.

The early Piano Quintet of 1903, withdrawn by the composer and embargoed by his widow until the 1990s, is firmly late-Romantic (a reminder that RVW was a Victorian till his late 20s) and doesn’t sound much like his later music. Again, file under “interesting”. Duncan Riddell’s Lark (with Bebbington) is good, but there are of course plenty of good Larks out there. More of a revelation is the Romance for viola (Abigail Fenna) and piano, only premiered after RVW’s death. Darker than the Lark, it builds up quite a head of steam, before returning to a shadowy calm. Bernard Hughes

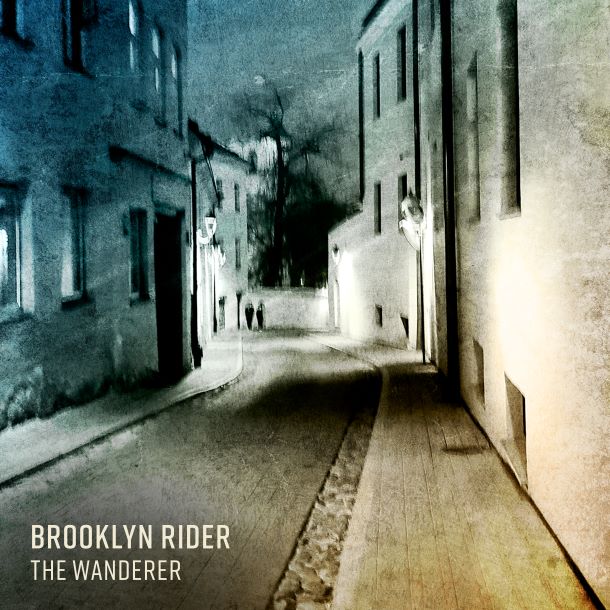

Brooklyn Rider: The Wanderer (In a Circle Records)

Brooklyn Rider: The Wanderer (In a Circle Records)

An exploration of “memory and remembrance, melancholy and bliss, old and new, and life and death”, this new live album from Brooklyn Rider (the group based in, er, Brooklyn) was recorded in the rich acoustic of a stable-turned concert hall in Paliesius, Lithuania. The sound is spectacularly vivid, and having the audience applause included feels entirely right. Gonzalo Grau’s Aroma a Distancia makes for a beguiling opener, an evocative seven-minute exploration of Grau’s musical and cultural influences, taking in his Venezuelan childhood and spells spent in Spain and the US. Grau. Wistful passages are offset by snatches of dance music, the quartet’s members adding clicks and taps. The abrupt end is striking, as if one’s suddenly woken from a daydream. Osvaldo Golijov’s Um Dia Bom, another Brooklyn Rider commission, traces a life as narrated to a child in five short movements. We begin in a cradle and finish with “the graceful, endless fall of a feather from the sky”. Repeated hearings throw up new things to love about the work, like the graceful dance accompanied by heavy rain in the second movement, and the fourth section’s ghostly gallop, accompanied by quotes from a blues song. The quartet ends with a barely audible whisper. Truly a life well lived.

An intense, viscerally-exciting performance of Schubert’s D810 Death and the Maiden takes us down a darker path, the players stressing the lyricism as much as the angst. The second movement’s variation sequence flows beautifully, and the 6/8 finale really moves. Schubert’s bleak coda really shocks here, the hoped-for D major resolution snatched away in the final bars.

Add comment