Brahms: The Four Symphonies, Piano Quartet No. 1 (orch. Schoenberg) Luzerner Sinfonieorchester/Michael Sanderling (Warner Classics)

Brahms: The Four Symphonies, Piano Quartet No. 1 (orch. Schoenberg) Luzerner Sinfonieorchester/Michael Sanderling (Warner Classics)

Some like their Brahms thick and dark. Others, well, will like what we get here, a more transparent, less granitic take on four of the most-recorded works in the orchestral repertoire. Michael Sanderling’s conductor father Kurt had a reputation for dourness and intensity, but these performances tend towards the light and lyrical. You’ll find more doom-laden accounts of Symphony No. 1’s slow intro, but the fast main section is as exciting as any on disc, and the central movements are exquisite. The finale’s introduction is marvellous, presumably because Swiss hornists are used to playing alphorns, and the big trombone chorale overwhelms, in a good way. The Lucerne brass also excel in Symphony No. 2, Sanderling’s feel for line really making Brahms’s melodies sing. There’s so much timbral clarity, the woodwind lines singing out. An expansive take on the finale never sags, timpanist Iwan Jenny’s contributions especially telling.

Symphony No. 3’s tricky first movement opens well, Sanderling really paying attention to articulation in Brahms’s syncopated string parts. The “Allegro grazioso” has a gorgeous lilt, and the symphony’s soft close is beautiful. Sanderling accentuates the positive in No. 4, the shadows tempered by autumnal sunlight, the third movement scherzo full of life. And, as a hefty bonus, we get Schoenberg’s transcription of the G minor Piano Quartet (referred to in the notes as “a kind of posthumous Fifth symphony”). Listening to it straight after the symphonies highlights how much of the piece sounds like authentic Brahms, despite Sanderling relishing the eccentricities. Muted trombones? Xylophone? That they’re totally inauthentic has never bothered me, and this is a thrilling and entertaining performance of a work I’m desperate to hear live. Sanderling lets rip in the third movement’s bombastic climax, and the work’s coda is uproarious. A very decent set, reasonably priced, with each symphony on a separate CD.

Nielsen: The Symphonies Danish National Symphony Orchestra/Fabio Luisi (DG)

Nielsen: The Symphonies Danish National Symphony Orchestra/Fabio Luisi (DG)

There’s much to enjoy here. Fabio Luisi’s Danish players tear into the opening of Nielsen’s Symphony No. 1 with an energy and enthusiasm that had me on side immediately. This is a delightful, original work; that it closes in a different key to the one it starts in one of its many striking features. Not that you’d necessarily notice. Nielsen was a string player, but it’s the highly individual woodwind writing which grabs one’s attention here. Luisi relishes the counterpoint and drives the symphony home to a buoyant conclusion. He takes the third movement much too quickly, but I’ll forgive him. Symphony No. 2, subtitled “The Four Temperaments”, is better still, brass snarling in the choleric first movement and never flagging an upbeat finale which comically runs out of steam near the close. The first movement of the “Sinfonia Espansiva” really swings, Luisi relishing the crazy waltz at its heart. Singers Fatma Said and Paile Knudsen are outstanding in the slow movement’s vocalise, and the “Allegretto un poco” has bite. But the finale is a let-down, Luisi’s core tempo too sluggish for comfort. Bernstein’s famous 1966 performance is almost as expansive but never feels this heavy.

This “Inextinguishable” is mostly excellent, the first movement propulsive and exciting, the ensuing intermezzo full of charm. Luisi relishes the angular string lines in the “Poco adagio quasi andante” and his duelling timpani in the last movement whip up a storm. The coda is impressive despite too slow a tempo. Symphony No. 5 features terrific clarinet and side drum solos, the latter vainly attempting to stop the first movement’s flow. Jens Cornelius’s lucid booklet essay quotes from an early review of a Stockholm performance, audience members leaving the hall “with horror and anger etched onto their faces.” This music hasn’t lost its power to shock and amaze. Luisi paces the second half well, with some radiant string playing and an electrifying close.

After which, the 6th Symphony can seem a disappointment. Not here. The first movement’s blend of innocence and bitter experience should be this unsettling, and the terrifying outburst nine minutes in is as potent as the dissonant chord heard in Mahler’s 10th, the shrill woodwind scream sounding like a warning siren. We get delicious trombone sneers in the “Humoreske”, and the near-atonal violin writing in the little “Proposta seria” is immaculate. Luisi makes the finale’s variation sequence cohere nicely, with suitably vulgar brass intrusions in the waltz section and a mischievous, unsettling pay-off; violins soaring heavenwards before a bassoon fart brings us crashing back to earth. It’s great, and the best recording of this quixotic symphony I’ve heard on disc. So, a few odd tempi withstanding, this is an excellent set, well-engineered and magnificently played. The booklet contains some appealing colourised photos of the composer, though the cover art looks cheap and sloppy, giving little hint as to the vibrant, life-enhancing delights lurking inside.

Alex Paxton. Happy Music for Orchestra (Delphian).

Alex Paxton. Happy Music for Orchestra (Delphian).

ilolli-pop (Nonclassical)

Alex Paxton’s music is perhaps not for the faint-hearted, but for those sick of the same-old-same-old it comes as a bracing dose of restorative medicine. His is a manic, full-frontal, maximalist music, coming at you like a freshly-unleashed tiger, with an energy that is both inspiring and a bit exhausting. It lashes together unlikely travelling companions: African water drumming, free jazz, György Ligeti and Bob Godfrey’s animated series Roobarb and Custard, all with the chaotic energy of a primary school classroom (Paxton was himself a teacher while creating these projects). Above all, it is brave pursuit of a self-made vision, much of it recorded on a laptop in Paxton’s flat, as a gesture of defiance against the “classical music gatekeepers” who would normally keep “outsiders” like him away from the mainstream.

But these two albums are on the well-respected labels Delphian and Nonclassical. The happiness of Happy Music is not a breezy cheerfulness but more hard won, foregrounding frenetic activity, occasionally receding into stasis: Matthew Herd’s alto sax solo in Strawberry is a lovely counterbalance to Paxton’s own hyperactive trombone improvisation earlier in the piece. As the album goes on there is a gradual move to gentler territory; the laconically titled final track Bye, perhaps my favourite, begins with a nostalgic chorale which becomes progressively more highly-strung.

ilolli-pop was released in September 2022 on Nonclassical, but had a similar genesis as Happy Music, being recorded and edited by Paxton himself, using a varying line-up of collaborators, billed as Dreamusics Ensemble. There is the same quality of good-natured bedlam, Paxton’s trombone prominent in the unruly commotion, the music endlessly referential but also spontaneous and intuitive. The title piece is a spectacular multi-movement work commissioned by Ensemble Modern: it made me think of Harrison Birtwistle but with a broad grin instead of dour frown. Sometimes Voices reminded me of Aphex Twin, Corn-Crack Dreams of Louis Armstrong’s Hot Five transported in a time-machine – and it all finishes with Mouth Song, a virtuosic solo for Paxton, which is a love-song to his brass band heritage, with its combination of melody and competitive display. These albums are definitely recommended, although perhaps to be consumed in sips rather than big swigs, as this is seriously intoxicating music. Bernard Hughes

ilolli-pop was released in September 2022 on Nonclassical, but had a similar genesis as Happy Music, being recorded and edited by Paxton himself, using a varying line-up of collaborators, billed as Dreamusics Ensemble. There is the same quality of good-natured bedlam, Paxton’s trombone prominent in the unruly commotion, the music endlessly referential but also spontaneous and intuitive. The title piece is a spectacular multi-movement work commissioned by Ensemble Modern: it made me think of Harrison Birtwistle but with a broad grin instead of dour frown. Sometimes Voices reminded me of Aphex Twin, Corn-Crack Dreams of Louis Armstrong’s Hot Five transported in a time-machine – and it all finishes with Mouth Song, a virtuosic solo for Paxton, which is a love-song to his brass band heritage, with its combination of melody and competitive display. These albums are definitely recommended, although perhaps to be consumed in sips rather than big swigs, as this is seriously intoxicating music. Bernard Hughes

Gabriel Pierné: Complete Piano Works, Chamber, Orchestral & Vocal Music (Warner Classics)

Gabriel Pierné: Complete Piano Works, Chamber, Orchestral & Vocal Music (Warner Classics)

Flogging hefty compilations of French music is about as niche an industry as you’ll find, and Warner Classics’ custodianship of the Erato back catalogue means that they’re probably market leaders. Their recent big boxes of Debussy, Fauré, Ravel, Roussel and Saint-Saëns are worth anyone’s time, and this latest one celebrates Gabriel Pierné. Born in Metz in 1883, Pierné was a friend of the young Debussy while studying at the Paris Conservatoire where his teachers included Franck and Massenet. Pierné later recalled the time he spent in Italy after winning the Prix de Rome as “the best three years of my life,” meeting Liszt and Grieg along the way. He became a celebrated pianist, organist and conductor as well as a composer, directing the 1910 Paris premiere of Stravinsky’s Firebird. He really should be better known outside France.

Pierné's delightful Piano Concerto isn’t included here, so I’d suggest starting with CD 6. It contains the irresistibly catchy Marche des petits soldats de plomb and a delightful Konzerstuck for harp and orchestra. The three Paysages franciscains are superb; listen blind and you’d swear you were listening to something by Respighi. Another good entry point is an extended suite from the full-length ballet Cydalise et le chèvre-pied; the opening number, “L’ecole des Aegipans” is two minutes of delicious quirkiness, and something you’ll be compelled to listen to on a loop. There are echoes of Ravel’s Daphnis and a few passages which sound as if they’ve been lifted straight from The Firebird. Why isn’t this score better known?

Pierné’s complete piano works fill four discs, played with style by Belgian pianist Diane Andersen. Most are miniatures, and all are worth exploring. I keep returning to the six-movement Album pour mes petits amis, the sequence finishing with the original version of the “Marche des petits soldats de plombe”. Do sample Les enfants à Bethléem, despite this being early summer; this large-scale Christmas cantata features some magical writing for children’s choir, and even contains a part for the donkey. Chamber works include Pierné’s dark but absorbing Piano Quintet and an attractive violin sonata, also given in a flute transcription. Two discs of historical recordings are absorbing, the curios including two late numbers for saxophone quartet and the “divertissement chorégraphique” Giration, scored for piano and ten instruments and designed to fill two sides of a 78rpm record. I’ve lived with this box set for several months, and haven’t yet discovered a piece I haven’t enjoyed. The performances are consistently good, and the booklet essay provides a detailed account of Pierné’s life and career. An unmissable bargain – buy this before it disappears.

I Watch You Sleep: Scott Dunn Celebrates Richard Rodney Bennett with Claire Martin and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (Stunt Records)

I Watch You Sleep: Scott Dunn Celebrates Richard Rodney Bennett with Claire Martin and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (Stunt Records)

It is always good to be reminded what a unique, many-sided presence in British music Richard Rodney Bennett (1936-2012) was. The most incongruous thought which comes to mind when hearing this “lush recording” (as Scott Dunn’s sleeve note has it), is that RRB was one of the few composers to have studied with Boulez and attended the Darmstadt summer school in the 1950s. Forget that thought: the 1950s temple at which arranger Scott Dunn chooses to worship here is a very different one: Nelson Riddle-era Capitol Studios, perhaps. The American songbook was very much home territory for Richard Rodney Bennett. As Claire Martin once told me in an interview: “(RRB) grew up listening to and loving all the great writers, Arlen, Berlin, Gershwin, Porter etc, and loved all the jazz singers that sung the songs, especially Carmen McRae (who was his favourite), Shirley Horn and Chris Conner. He knew a lot about songs, every obscure verse, every writer, what year the song was written and usually the publisher too.”

The title track is a particularly interesting research rabbit hole to disappear down. “I Watch You Sleep” was written for the Richard Gere/ John Schlesinger film “Yanks”, although IMDB doesn’t list it. There is a superb recording of it by the great Shirley Horn, and the langorous mood Horn finds in her recording of the song sets the core vibe for the first five songs, with resplendent full orchestra recorded in Blackheath Halls. The fifth of them, Vernon Duke’s “Round About”, is a demonstration of how Claire Martin can prosper and really shine at an unbelievably slow tempo. Things do lighten up after that, which brings the classy trio of Rob Barron, Jeremy Brown and Matt Skelton to the fore. I particularly liked “Goodbye for Now.” This song is nothing like the insipid Sondheim/ Barbra Streisand song with the same title from “Reds”, but an utterly mischievous lyric with some irresistibly daemonic rhymes by Charles Hart set by RRB. The song is a pre-emptive will, in which possessions are left to people for unusual reasons, accompanied by a sly cor anglais from Maxwell Spiers. Love it. Sebastian Scotney

Toccatas and Fantasies – music by JS Bach, CPE Bach and Peter Seabourne Konstantin Lifschitz (piano) (Willowhayne Records)

Toccatas and Fantasies – music by JS Bach, CPE Bach and Peter Seabourne Konstantin Lifschitz (piano) (Willowhayne Records)

It was pianist Konstantin Lifschitz’s idea to commission new pieces to play alongside seven Bach pieces, composer Peter Seabourne following the sectional structures of the Bach toccatas but consciously avoiding what he describes as ‘neo-Baroquery’ (“there was plenty of that in the 20th century, arguably too much…”). Those worrying that this double album will be overstuffed with fast, noisy music needn’t worry, Seabourne pairing each of his seven toccatas with introspective companion pieces. The mixture works well, and you can imagine listening to the whole lot in a concert setting, a cerebral but stimulating experience. Lifschitz’s incisive, lively playing makes a persuasive case for Bach on a Steinway; the fugal passages in the early BVW 910 toccata are really exciting, preceded by a ruminative introduction where the broken chords sound as if they’re strummed on a guitar. Moving abruptly from that work to Seabourne’s spiky, extrovert “Toccata No. 1” works, despite the difference in musical language, and the introspective “Fantasia Lachryma” which follows cools things down nicely. Toccata No. 3 is another highlight, the stabbing chords interrupting the forward motion comically irregular, as if Seabourne’s trying to swat a fly, followed by an irresistibly romantic “Fantasia Tenebrosa.”

Lifschitz follows the pair with an imposing account of Bach’s D minor toccata and an effervescent “Fantasia in E flat” by his son CPE, a piece so fresh and individual-sounding that it’s hard to believe it dates from the 1740s. I like Lifschitz’s stern take on the introduction to Bach’s E minor toccata, and how the solemnity is punctured by Seabourne’s exuberant 5th toccata. Seabourne throws in an “Aria Sarabanda con Variazoni” as the penultimate track, an entertaining nine-minute nod to the Goldberg Variations, before Lifschitz brings things to a close with a joyous account of Bach’s G major toccata. Excellent recorded sound and lively sleeve notes too – an enjoyable set.

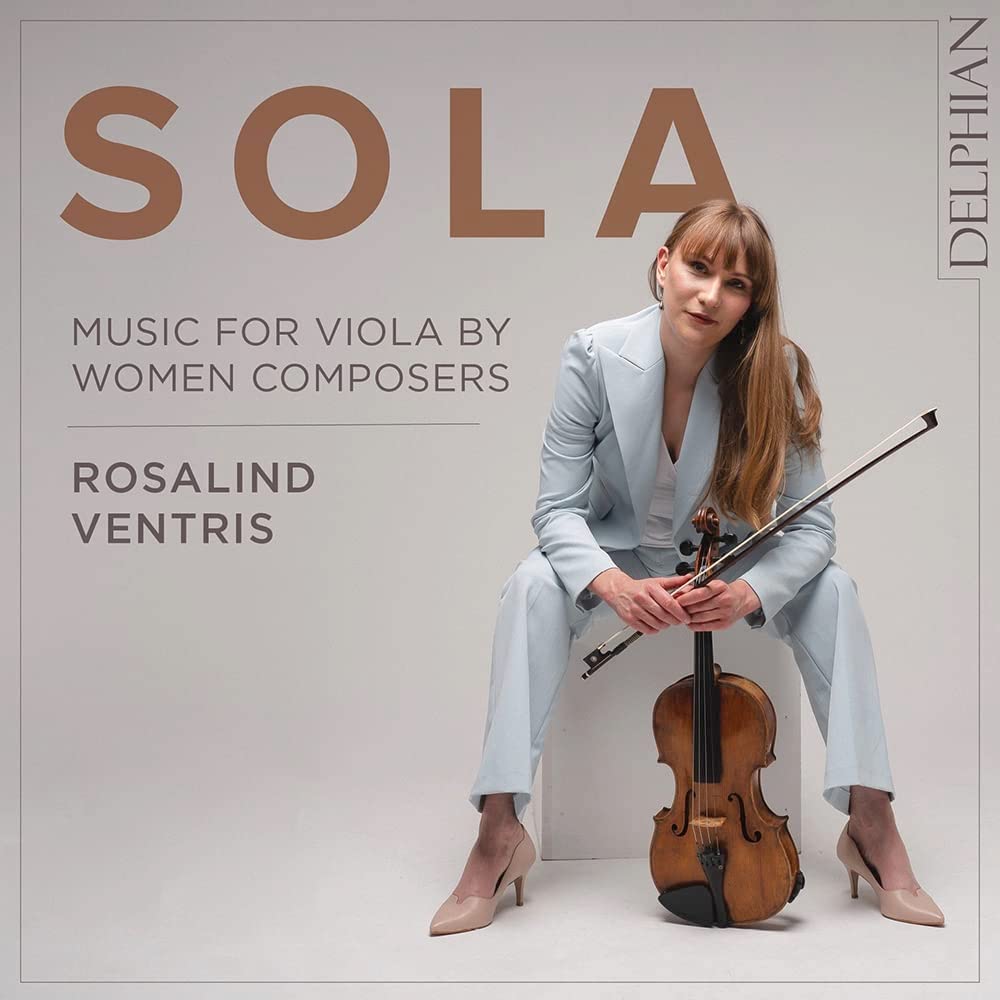

Sola Rosalind Ventris (viola) (Delphian)

Sola Rosalind Ventris (viola) (Delphian)

What would once have been considered a niche-within-a-niche, the release of Sola speaks well for the adventurousness of independent classical labels today. Where the major labels used to dominate with yet more Bruckner and Beethoven, now we get labels like Delphian, Orchid and Signum (to name just three of many) committing to repertoire that wouldn’t have got a look-in previously. So this beautifully played disc of “music for viola by women composers” deserves plaudits not just for the violist Rosalind Ventris, but for the label. At its best, the viola can match the athleticism of the violin with the emotional heft of the cello, all in one package. Rosalind Ventris’s playing captures both of these aspects, and more besides, in a compendium of works by 20th and 21st century composers, from Elizabeth Lutyens (1906-83) to Amanda Feery (b.1984).

Picking out favourites is always going to be invidious, and there is something here for all tastes. Feery’s chilly Boreal is given a poised and arresting performance, Ventris finding a glassy stillness. By contrast, Elizabeth Maconchy’s varied Five Sketches (from 1983) are lithe and lyrical, with a punchy energy in the faster movements. Sally Beamish’s Penillion is a competition piece in which Ventris can show off her full technical armoury. There is virtuosity aplenty but also heart, as the music subsides into a drone-accompanied Welsh folksong. It is nicely juxtaposed by something for those with a strong stomach: Lutyens’s Echo of the Wind is typically challenging, bone-dry and uncompromising – but utterly gripping. Bernard Hughes

Add comment