Louise Farrenc: Symphonies 1-3 Insula Orchestra/Laurence Equilbey (Erato)

Louise Farrenc: Symphonies 1-3 Insula Orchestra/Laurence Equilbey (Erato)

Louise Farrenc (1804-1875) is not perhaps the best-known name among pre-20th century women composers garnering increased attention recent years – but she might be the best. She managed to achieve success in her own lifetime, even in the field of the symphony – the form most guarded by the high-art (male) gatekeepers – before pretty much disappearing from music history. This release of Farrenc’s three symphonies (plus two overtures) by the Insula Orchestra, playing on period instruments, makes a very persuasive argument for her taking her place in the concert canon. Insula was formed in France in 2012 by conductor Laurence Equilbey, specialising in 17th and 18th century repertoire, but the ensemble and conductor feel equally at home in this later music. Written in the 1840s, these symphonies are conservative in style and harmonically in the world of Beethoven, without much of a nod to her almost exact contemporary Berlioz. The Beethoven link is direct, through her teachers Reicha and Hummel, and Farrenc shows herself at home in the large-scale symphonic form that Beethoven established.

Farrenc was a pianist – she taught as the first female full professor in the history of the Paris Conservatoire – but never learned to play any orchestral instrument. This didn’t stop her writing idiomatically and assertively for orchestra, with notably prominent wind lines, like the clarinet at the beginning of the first symphony. The strings are also muscular and insistent, no mimsiness from these period instruments. But there are also moments of delightful relaxedness, in the viola and cello melodies in the finale. There is a stern forthrightness in the third symphony, whose premiere was perhaps Farrenc’s career highlight. Alternations between forceful tutti passages and delicate chamber textures are a winning feature of Farrenc’s style. The second symphony, on disc 2 of this collection, is perhaps the most formally interesting, especially in its finale, which is radical by the means of looking backwards rather than forwards. Its extended fugato and almost dainty baroque textures are deftly played by Insula, an ensemble whose future recordings I will definitely look out for. Bernard Hughes

Nina Platiša: Za Klavir (Canada Council for the Arts)

Nina Platiša: Za Klavir (Canada Council for the Arts)

Michael Blake’s Afrikosmos (reviewed here) was based on Bartok’s epic Mikrokosmos, whereas Nina Platiša’s cycle of 26 short piano pieces was directly influenced by Bartok's For Children. Platiša, born in Belgrade but now resident in Canada, recognised the kinship between Bartok’s field recordings and the Balkan folksongs she learned as a child. These pieces aren’t transcriptions, but they sound as if they could be, Platiša recalling that “they seemed to issue from me naturally, without any kind of force.” The simplest numbers in Mikrokosmos can pack a real punch, and it’s the same with Za Klavir, a useful reminder that “music doesn’t have to be complex or impossible to play in order to be estimable or emotionally resonant”. There’s not a wasted note, Platiša knowing instinctively how many times a theme can be repeated or varied. Take No. 4, a description of cloudy Balkan skies, its plaintive 2/4 dance melody heard over a catchy ostinato. No. 11’s unchanging two-chord backing is directed to be played “like in a beautiful dream,”, while a halting melody attempts to take wing above. No. 14, described as “a more dynamic cousin” repeats the trick, beautifully.

No. 17’s stops and starts really do sound like a child practicing, finishing with a nicely emphatic low G. The broken chords at the start of No. 19’s suggest a Bach prelude before turning into a folksy stomp, Platiša’s sound engineer Jonas Bonnetta charged with making the recording feel “like it was coming from a smoky, burgundy lounge.” No. 21 is daringly spare but full of rhythmic punch, and No. 24’s staccato chords never occlude the melody, a bona fide earworm. Platiša’s unaffected playing suits the music perfectly, and the close, intimate balance is what these pieces need. Delightful, in other word. The sheet music is available for purchase on Platiša’s website, and do have a look at the short films created to accompany several of the pieces.

Rachmaninoff: Symphonies 2 and 3, Isle of the Dead Philadelphia Orchestra/Yannick Nézet-Séguin (DG)

Rachmaninoff: Symphonies 2 and 3, Isle of the Dead Philadelphia Orchestra/Yannick Nézet-Séguin (DG)

Symphony No. 2, Vocalise Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra/Leonard Slatkin (Naxos)

Hearing more Rachmaninov in his 150th birthday year has to be a good thing, and I’ve a small but significant pile of new recordings in the intray. Two sets of the piano concertos will be reviewed shortly, but I’ll start with CDs of symphonies and orchestral music. Do read Fiona Maddocks’ book Goodbye Russia, an entertaining and poignant look at the composer’s post-1917 career and output, showing how the need to earn a living as a travelling piano virtuoso affected Rachmaninov’s creative output: after leaving Russia, he wrote just six works. One of them being his Symphony No. 3 (1936), which really deserves to be heard more often. Rachmaninoff was proud of this three-movement piece (“personally I am convinced that this is a good work…”) and Sir Henry Wood was a fan. The neglect is baffling – this symphony is full of tunes, brilliantly orchestrated and ends with a bang. As with the valedictory Symphonic Dances, the music language is a winning mixture of the lush and the lean. Yannick Nézet-Séguin’s new Philadelphia recording is impressive. He’s less hard-driven than John Wilson’s exciting Chandos performance, the Philadelphia strings lending the first movement’s second theme a Hollywood sheen, portamenti never sounding self-conscious. Muted brass snarl and it’s good to hear the tuned percussion cutting through in the development. The movement’s coda glows. He’s also good in the slow movement’s scherzo section, where you can really hear the woodwind triplets chattering behind the incisive main theme. The finale’s gear changes are negotiated with aplomb, and there’s a star turn from the principal flute two minutes before the end, the final bars sounding both angry and triumphant. Perhaps Nézet-Séguin’s Isle of the Dead should have opened the disc; though beautifully played, it’s a bit of a mood killer.

Symphony No. 2 fills the other disc. The Philadelphia Orchestra’s string section was one of the many things which Rachmaninov appreciated about life in the USA, and a famous analogue recording made during the Eugene Ormandy era sounds good. Nézet-Séguin’s uncut performance lasts for 62 minutes but never drags. The energy he brings to the scherzo and finale is infectious, and he manages the tempo shifts beautifully, as with the scherzo’s lush second theme. His “Adagio” boasts an eloquent clarinet solo. What stopped me really loving the performance is the recorded sound, which can be a touch dry and oppressive. Instead, invest in Naxos’s reissue of a 1979 performance by Leonard Slatkin, taped at the beginning of his tenure as Music Director of the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra. Originally released on the now defunct Vox label, it’s both a superb reading and an audiophile’s delight. We get as much detail as we do on the DG set, but everything feels warmer, fresher and more seductive. Fans of the symphony needn’t throw out their Previn/LSO discs, but should supplement them with Slatkin. Everything’s so well-balanced and natural-sounding; it’s Slatkin ensuring that we hear all the right details, not the engineers. His slow movement is as affecting as Previn’s, and the finale’s close is a burst of pure joy. As a bonus there’s the little Vocalise, which, though lovely, feels a bit of an anti-climax after the symphony’s emphatic E major ending. Slatkin recorded Rachmaninoff’s other orchestral works at the same time – hopefully Naxos will reissue the rest before too long.

Symphony No. 2 fills the other disc. The Philadelphia Orchestra’s string section was one of the many things which Rachmaninov appreciated about life in the USA, and a famous analogue recording made during the Eugene Ormandy era sounds good. Nézet-Séguin’s uncut performance lasts for 62 minutes but never drags. The energy he brings to the scherzo and finale is infectious, and he manages the tempo shifts beautifully, as with the scherzo’s lush second theme. His “Adagio” boasts an eloquent clarinet solo. What stopped me really loving the performance is the recorded sound, which can be a touch dry and oppressive. Instead, invest in Naxos’s reissue of a 1979 performance by Leonard Slatkin, taped at the beginning of his tenure as Music Director of the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra. Originally released on the now defunct Vox label, it’s both a superb reading and an audiophile’s delight. We get as much detail as we do on the DG set, but everything feels warmer, fresher and more seductive. Fans of the symphony needn’t throw out their Previn/LSO discs, but should supplement them with Slatkin. Everything’s so well-balanced and natural-sounding; it’s Slatkin ensuring that we hear all the right details, not the engineers. His slow movement is as affecting as Previn’s, and the finale’s close is a burst of pure joy. As a bonus there’s the little Vocalise, which, though lovely, feels a bit of an anti-climax after the symphony’s emphatic E major ending. Slatkin recorded Rachmaninoff’s other orchestral works at the same time – hopefully Naxos will reissue the rest before too long.

Shostakovich: Symphonies 6 and 15 London Symphony Orchestra/Gianandrea Noseda (LSO Live)

Shostakovich: Symphonies 6 and 15 London Symphony Orchestra/Gianandrea Noseda (LSO Live)

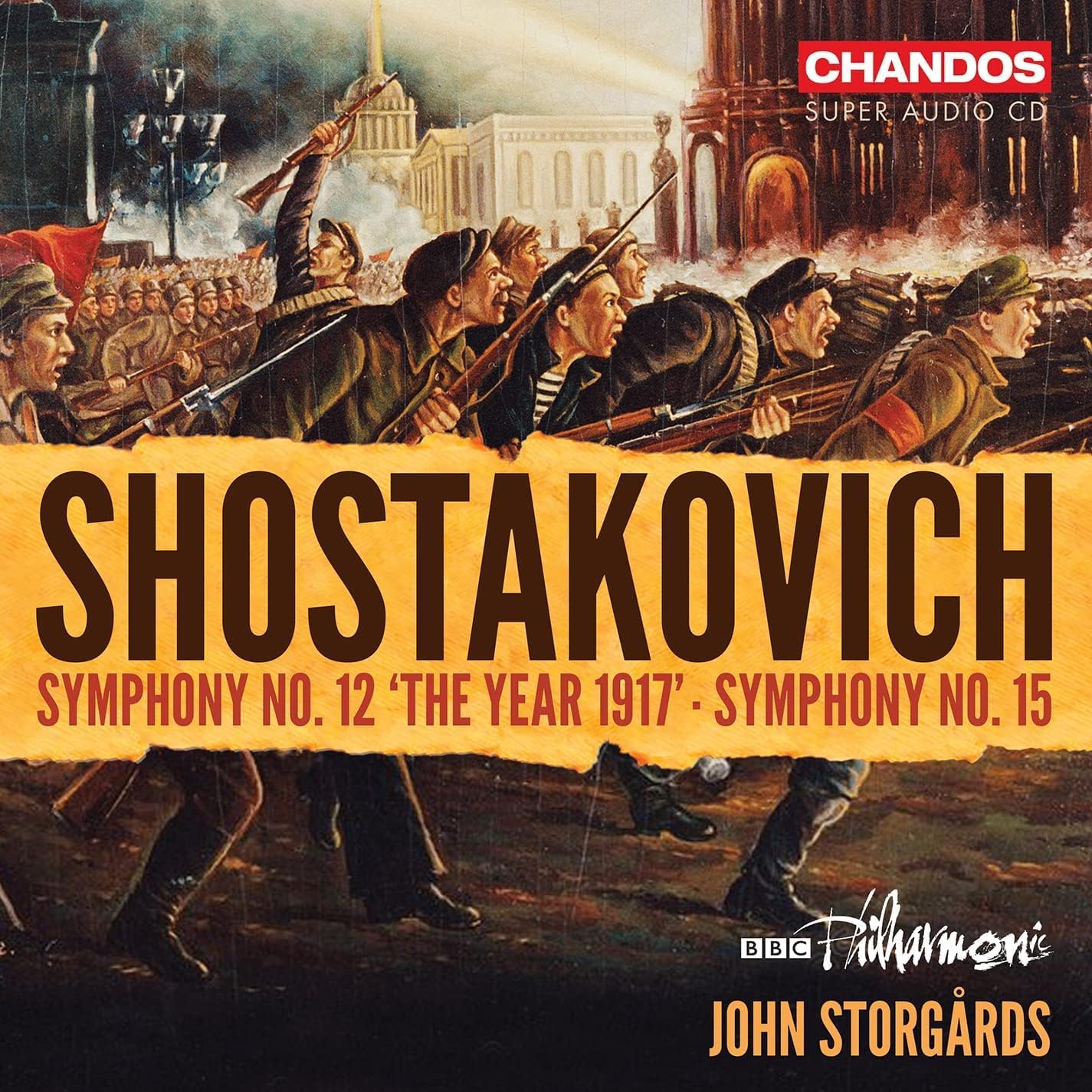

Symphonies 12 and 15 BBC Philharmonic/John Storgårds (Chandos)

There’s a lot of Shostakovich about too, and his 15th Symphony (premiered in 1971) must be the most recent symphony to come close to entering mainstream repertoire. The composer’s son Maxim conducted the premiere and the first recording, which we’re unlikely to see reissued anytime soon – a pity, as it’s a wonderful performance. Timings from Gianandrea Noseda and John Storgårds are pretty close and there’s not that much to choose between the two. The drier Barbican acoustic suits Noseda’s more abrasive take well; the bass drum thwacks in the first movement have plenty of weight and the trumpet writing really cuts through. Storgårds’ BBC Philharmonic make a more homogenous, blended sound, the brass chorale at the start of the slow movement sounding like Wagner. Slow movement and scherzo are excellent in both performances, the cello and trombone solos eloquent. After the finale’s shattering climax, Noseda makes the sentimental string theme’s reprise sound like music from another planet, the violin tone desiccated. Storgårds is more consolatory, the mood bittersweet. The enigmatic close is heartrending in both performances, with pin-sharp percussion.

Noseda’s coupling is the 6th Symphony, Storgårds offering the unloved 12th. No. 6’s opening slow movement is terrific here, Noseda’s chilly vistas punctuated by deep harp pedals and lonely flute solos. The two fast movements are witty and exciting, the exuberance tempered by a touch of menace. Storgårds has a harder job with the 12th, subtitled “The Year 1917”. Shostakovich had planned to compose symphonic tribute to Lenin for some years, eventually producing (in great haste, according to some sources) a bombastic crowd pleaser. It’s nowhere near as profound as the 11th or 13th symphonies, but Storgårds’ clear-sighted, emotionally direct account makes a persuasive case for the piece, the BBC Philharmonic brass and percussion going for broke in the last movement.

Noseda’s coupling is the 6th Symphony, Storgårds offering the unloved 12th. No. 6’s opening slow movement is terrific here, Noseda’s chilly vistas punctuated by deep harp pedals and lonely flute solos. The two fast movements are witty and exciting, the exuberance tempered by a touch of menace. Storgårds has a harder job with the 12th, subtitled “The Year 1917”. Shostakovich had planned to compose symphonic tribute to Lenin for some years, eventually producing (in great haste, according to some sources) a bombastic crowd pleaser. It’s nowhere near as profound as the 11th or 13th symphonies, but Storgårds’ clear-sighted, emotionally direct account makes a persuasive case for the piece, the BBC Philharmonic brass and percussion going for broke in the last movement.

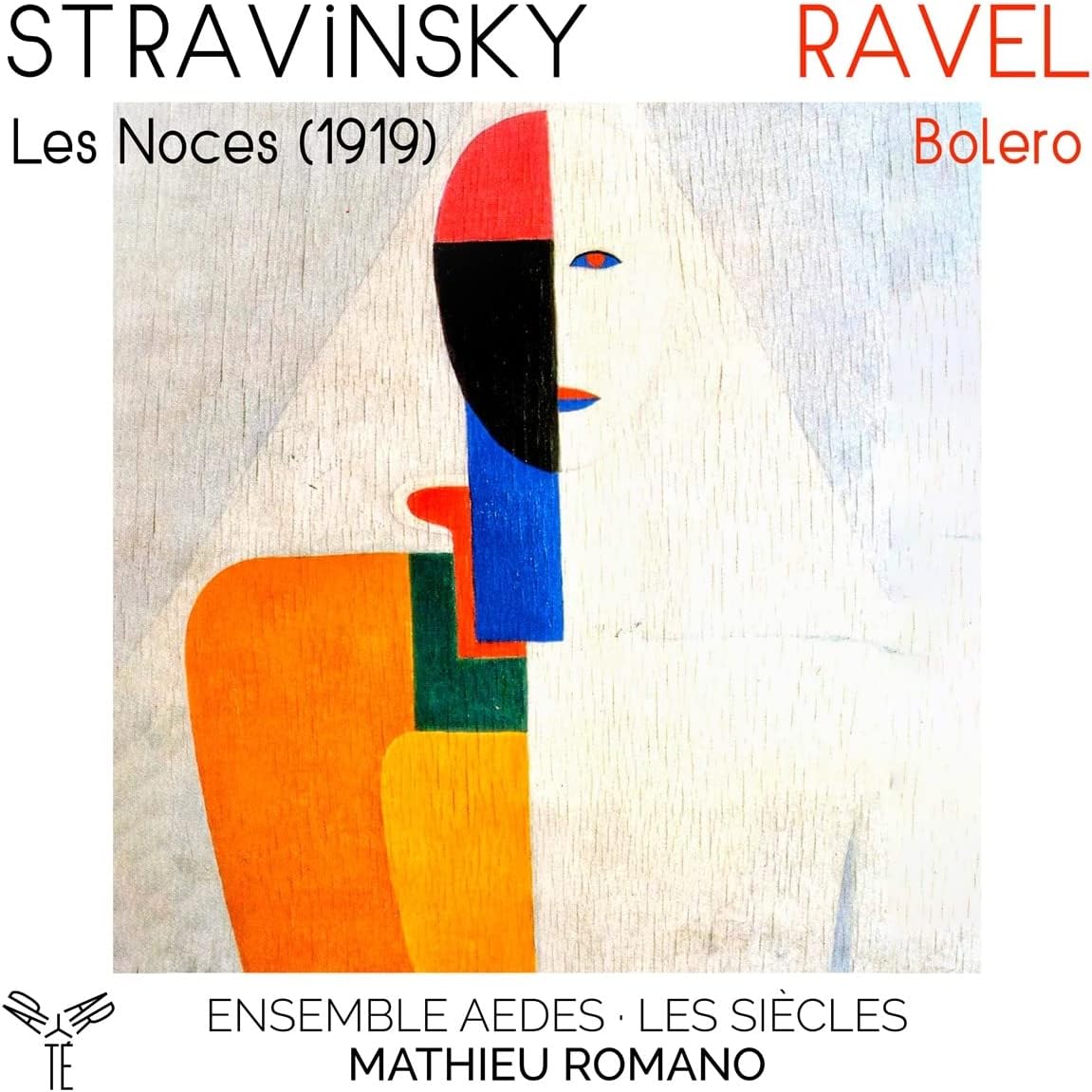

Stravinsky Les Noces (1919 version) Ensemble Aedes, Les Siècles/Mathieu Romano (Aparté)

Stravinsky Les Noces (1919 version) Ensemble Aedes, Les Siècles/Mathieu Romano (Aparté)

I have waited my whole adult life for this recording, and it doesn’t disappoint. Stravinsky’s Les Noces – in English “The Wedding” – had a protracted genesis, in which the fastidious composer struggled to find the instrumental combination he wanted. For this extraordinary ballet, depicting a traditional Russian peasant wedding in Stravinsky’s bracing hyper-modern musical language of the 1910s, the composer needed to find an instrumentation to be a lens through which the stylised action could be refracted. Initially a conventional symphony orchestra accompanied the four solo singers and mixed chorus. This “1917 version” was first recorded by Peter Eötvös in 1988 – but Stravinsky didn’t feel a conventional line-up fit the bill. By 1923 – 10 years after starting the piece – he hit on the combination of four pianos and percussion, which is how the piece has been known ever since.

But in between (the “1919 version”) he experimented with a radical ensemble, combining the technologically cutting-edge and the deeply traditional: two cimbaloms (Hungarian hammered string instruments) alongside a pianola, plus percussion and harmonium. He only abandoned this version two scenes in because of the practical problems of co-ordinating the pianola with the live instruments. Robert Craft recorded these two scenes in the 1970s, albeit with live pianist in place of the pianola, but only now is the full piece recorded, with the two missing scenes scored (completely convincingly) by Theo Verbey and the pianola programmed digitally. And it is every bit as good as I had always thought it would be. The cimbaloms give the texture a folk music twanginess which softens the edges of the pianola. It is somehow busier and less monumental than the four-piano version, but always with an urgency and straightforwardness. The performances are first rate: Françoise Rivelland and Iurie Morar on cimbalom, Amélie Raison (soprano) and indeed all the singers of Ensemble Aedes are on top form. This is a recording Stravinsky fans must hear (although the composer himself himself never got to) if only for the stunning final minutes in which the hectic rushing-around falls away, and tenor Martial Pauliat is surrounded by a halo of bell-percussion, magical moments that are utterly Russian, utterly Stravinsky.

After which comes a bizarre coda: Ravel’s Bolero, scored for the same ensemble. It kind of works, as a novelty, the melody transalting surprisingly well to a soprano solo at the beginning. What is lost is the variety of the original scoring, with the tune here being passed around the handful of instruments (the piece runs to its full 15-minute length). But there are lovely new details like a tubular bell at the big key change and this quirky arrangement is certainly worth hearing, if not prompting the excitement of the Stravinsky. Bernard Hughes

Andreas J. Winkler - mit und ohne worte (TYXart)

Andreas J. Winkler - mit und ohne worte (TYXart)

“I do not share the view that one cannot, shall not or must not write sonatas, fugues and certainly not Lieder any more,” writes Cologne-and Salzburg-based composer Andreas J. Winkler (b.1974). He has a broad range of output; among his larger works there is an operatic treatment of Kafka’s “Metamorphosis”. Here we find smaller-scale works: fourteen of the twenty-one tracks on this CD are Lieder, mostly for soprano (Elena Puszta) and piano (Denis Ivanov), interspersed with short works for a chamber group of saxophone, violin or electronic violin ( Margarita Rumyantseva) , saxophones (Yuriy Broshel) and piano. Winkler acknowledges a debt to Alban Berg; the musical language here is at the edges of tonality. The choice of poets takes the listener down interesting paths. The poet whom Winkler has set the most is former journalist Sabine Bergk. They have worked for a decade together and more than half of the poems he has set are by her. Her language is direct and communicative rather than allusive/ ‘poetic’ and Winkler says that his method is to locate a “Grundstimmung” (basic mood) which matches a poem. Winkler has said in a podcast that he finds the music to her poems tends to come relatively easily. That feeling of ease is there particularly in “Der friedliche See”, an audience-friendly song.

At the opposite end of the scale are the poems of the great Austrian poet Ingeborg Bachmann (1926-1973), which are much denser, and where every word can be a source of surprise in both its meaning and its rhythmic implications. As a composer Winkler is much more deeply reactive and engaged here. For the listener, a much more intensive and engaged level of concentration is the norm. Among contemporary composers, Thomas Larcher has also set Bachmann poems, but it is relatively infrequent. The instrumental contribution is strong. There is some very punchy baritone saxophone playing on Winkler’s setting of one of the great, dark, pagan expressionist poems “Der Gott der Stadt” from 1910 by Georg Heym. "Attic" has interesting hints of the "Intermède" from Messiaen's "Quatuor pour la fin du temps". An interesting and varied collection of works showing Winkler's range. The recording, supported by the region of North Rhine Westphalia and made in Essen, is exemplary. Sebastian Scotney

Add comment