Kabeláč: Eight Preludes, Motifs from Exotic Lands, Smetana: Dreams Jan Bartoš (piano) (Supraphon)

Kabeláč: Eight Preludes, Motifs from Exotic Lands, Smetana: Dreams Jan Bartoš (piano) (Supraphon)

Anyone interested in 20th century music should investigate Supraphon’s box set of Miloslav Kabeláč’s eight symphonies. when you've done that, get hold of pianist Jan Bartoš's engrossing recital disc. Kabeláč’s relationship with the communist regime in post-war Czechoslovakia was often strained, though things improved after Stalin’s death. He was fascinated by cosmology (“…everything in the world and the universe has a centre around which it revolves…”) and his music, though often dissonant, is invariably rooted in tonality. Kabeláč’s Eight Preludes for Piano were premiered in 1957 and have an otherworldly feel. The “Preludio ostinato” sounds simultaneously hopeful and resigned, the opening bars’ upward trajectory running out of steam. No. 3, “Prelude sognante” suggests a glimpse of the world through half-closed eyes, the mood shattered by a thunderous “Prelude corale”. They’re terrific little pieces, wonderfully played here by Jan Bartoš. Listen to how he nails the closing prelude’s fierce, defiant coda.

Equally fascinating is Kabeláč’s Motifs from Exotic Lands from 1958-9: 10 glimpses of what we’d now call "world music", filtered through his compositional sensibilities. Bartos’s booklet essay includes Kabeláč’s recollection of discovering non-western music (“a literally shocking experience… for a person trained solely in European music, a revelation…”. I’ve had the “Javanese Motif” on repeat in recent months, and a sparely harmonised East Asian flute improvisation is haunting. Presumably Kabeláč had to rely on recordings as source material, the set including Brazilian, Middle Eastern and Inuit themes. That Kabeláč especially loved Indian and Japanese music, lecturing on both, makes you warm to him even more. Smetana’s Dreams makes for an appealing filler, a set of six nostalgic “morceaux caractéristiques”. “In the Salon” is fun, Bartos’s tempo ebbing and flowing as if he’s conversing with assorted acquaintances. His “By the castle” is imposing, and Smetana’s take on Bohemian folk festivities is great fun. A remarkable disc, all three performances captured live in exemplary sound.

Friendship Simon Trpčeski (piano) (Linn)

Friendship Simon Trpčeski (piano) (Linn)

Hearsay Atlantic Chamber Ensemble (Imaginary Animals)

I’m not sure if critics are allowed to be fans too? A degree of disinterested coolness is important of course, but there is also a place for expressing a very keen enthusiasm. I freely admit to being smitten with the music of Guillaume Connesson (b.1970) and eagerly keep a lookout for new recordings of his work, and here are two albums in the same year with different versions of the same piece, and one of my favourites. Connesson’s Sextuor dates from 1997 and has been previously available on the Sony compilation of his chamber music. It is now the opener to the album Hearsay by the Atlantic Chamber Ensemble, and the finale of pianist Simon Trpčeski’s Friendship album, in a re-scored version that adds percussion. It works well in both roles and versions, its extrovert charms and captivating middle movement served well in both performances.

Simon Trpčeski toured the programme on his album widely in 2022, and I reviewed the Wigmore Hall performance for theartsdesk. It puts the Connesson alongside the Brahms Piano Quartet no.3 alongside Pande Shahov’s three-movement Quintet, the Connesson arranged by the percussionist Vlatko Nushev, and who is its hyperactive star turn. The Brahms is earnest and eloquent, Trpčeski leading from the front, and Shahov’s Quintet pointillist and lithe – but it’s the Connesson I’m here for. On paper at risk of gilding the lily, adding the percussion actually gives the Sextuor (renamed as Divertimento) an expansiveness and plays up the lively humour of the outer movement. The middle one, though, is all about Hidan Mamudov’s silky clarinet solo, underpinned by pianissimo bass drum and suspended cymbal. It’s magical.

The Sextuor kicks off the Atlantic Chamber Ensemble’s Hearsay, and it is immediately reassuring to have the double bass (Ayca Kartari) and oboe (a poised Shawn Welk) back in the picture (they are missing from the Divertimento line-up). The first movement is an homage to John Adams, albeit with Poulenc popping up the whole time, mercurial and flighty. There is odd editing at the end of the second movement, with the end going into the following track – I have no idea why, but will make for a strange listening experience if not listening to the whole piece. But the last movement is as sparkling and “festif” as its heading requests. The rest of Hearsay is as varied as Friendship. Óscar Navarro’s Juego de Ladrones, for a classic wind quintet line-up, has a multitude of characters, switching from playful dance to unlikely reminiscence of Purcell. Gerald Finzi’s Eclogue is an unlikely bed-fellow for both the Navarro and Mason Bates, whose incorporation of electronics into his Rags and Hymns of River City adds another colour to the winds, particularly groovy in “The Slip”. I hadn’t heard of the Atlantic Chamber Ensemble, who are based in Richmond, Virginia before, but enjoyed both their playing and their programming. Bernard Hughes

The Sextuor kicks off the Atlantic Chamber Ensemble’s Hearsay, and it is immediately reassuring to have the double bass (Ayca Kartari) and oboe (a poised Shawn Welk) back in the picture (they are missing from the Divertimento line-up). The first movement is an homage to John Adams, albeit with Poulenc popping up the whole time, mercurial and flighty. There is odd editing at the end of the second movement, with the end going into the following track – I have no idea why, but will make for a strange listening experience if not listening to the whole piece. But the last movement is as sparkling and “festif” as its heading requests. The rest of Hearsay is as varied as Friendship. Óscar Navarro’s Juego de Ladrones, for a classic wind quintet line-up, has a multitude of characters, switching from playful dance to unlikely reminiscence of Purcell. Gerald Finzi’s Eclogue is an unlikely bed-fellow for both the Navarro and Mason Bates, whose incorporation of electronics into his Rags and Hymns of River City adds another colour to the winds, particularly groovy in “The Slip”. I hadn’t heard of the Atlantic Chamber Ensemble, who are based in Richmond, Virginia before, but enjoyed both their playing and their programming. Bernard Hughes

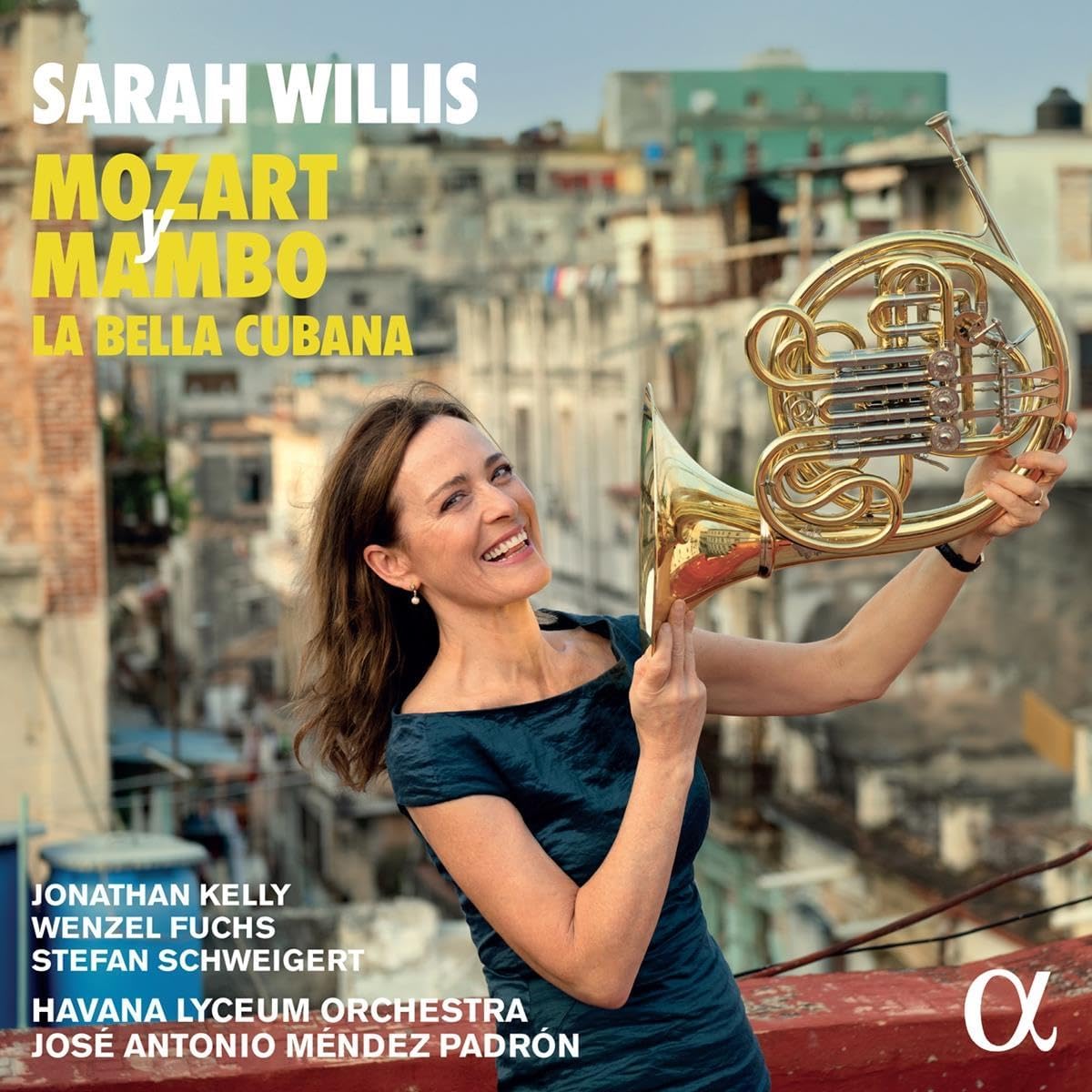

Sarah Willis: Mozart y Mambo – La Bella Cubana (Alpha Classics)

Sarah Willis: Mozart y Mambo – La Bella Cubana (Alpha Classics)

Sarah Willis’s Mozart Horn Concerto recordings are up there with the very best, recorded and released as part of her ongoing Mozart y Mambo project. This third volume contains No. 4, plus the K297b Sinfonia Concertante for winds. Both performances are good: Willis’s effortless legato is a big draw and she’s also happy to embrace the horn’s extrovert, earthy character, especially in this concerto’s ubiquitous 6/8 finale. Willis’s first movement cadenza is fun too, especially when highlighting her beefy low register. She’s stylishly accompanied by José Antonio Méndez Padrón’s Havana Lyceum Orchestra, and hearing these players grow in confidence with each instalment has been one of this series’ incidental pleasures. Whether the Sinfonia Concertante is authentic Mozart has never bothered me, and this account, Willis joined by three colleagues from the Berlin Philharmonic, feels totally idiomatic. The ensemble playing is marvellous, a highlight for me being the finale’s clucking introduction, Jonathan Kelly and Stefan Schweigert’s oboe and bassoon duet laugh-out-loud funny.

That’s Mozart taken care of. What about the three Mambo extras? My favourite is a lush arrangement of 19th century Cuban composer José White Lafitte’s “La Bella Cubana”, featuring the four wind soloists. The tempo change midway is nicely managed, Padrón’s orchestra never missing a beat. Edgar Olivero’s “Rondo alla Rumba”, played by Willis’s seven-piece Sarahbanda, bravely attempts to put a Cuban slant on the 4th Concerto’s Rondo, but the humour falls a bit flat. Jorge Aragon’s extended arrangement of Joseíto Fernández’s evergreen “Guantanamera” is glorious though, with a stellar contribution from trumpeter Harold Madrigal Frias and a telling vocal contribution from the orchestra. As with the earlier volumes, a percentage of the album’s profits will go towards providing new and donated instruments for young Cuban musicians.

Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 5, Schulhoff, arr. Honeck: Five Pieces Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra/Manfred Honeck (Reference Recordings)

Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 5, Schulhoff, arr. Honeck: Five Pieces Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra/Manfred Honeck (Reference Recordings)

New releases from this particular conductor/orchestra combo still feel like an event. You won’t find box sets of Beethoven or Mahler in Manfred Honeck’s Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra discography, Honeck preferring to record single discs of pieces he’s fond of, often with striking couplings. So it is with this new Tchaikovsky 5, taped live in June 2022. Flabby performances bore me to tears. Here, Honeck’s urgency is thrilling, the first movement’s “Allegro con anima” swift and exciting. This orchestra’s dark, voluptuous timbre feels entirely right for the piece, the Pittsburgh brass really making their presence felt. Transitions are well judged, musically and emotionally; I’d forgotten just how exciting this music can sound. William Caballero’s second movement horn solo is gorgeous, and the motto theme’s two reappearances are terrifying. The waltz is deftly handled, with some nifty bassoon playing and agile upper strings. We get a bold, propulsive finale, leading to a genuinely optimistic coda. It’s excellent, and one of the best modern performances out there.

If that’s not tempting enough, the filler is a must-hear, an orchestration by Honeck and the Czech composer and guitarist Tomáš Ille of the Five Pieces for String Quartet by Erwin Schulhoff. Composed in 1924 and dedicated to Darius Milhaud, they’re a by-product of Schulhoff’s “extraordinary passion for fashionable dances… there are times when I go dancing night after night...” Each movement affectionately parodies a dance genre, my favourites being the raucous Czech polka and a sinuous tango lasting nearly five minutes. Rescoring pithy quartet miniatures for vast orchestral forces is a bit of a gamble, but the results are incredible, with plenty of tuned percussion and some virtuosic brass writing. The closing “Alla Tarantella” is stunning, and reading about Schulhoff’s tragically early demise makes his loss more upsetting. Production values are as high as you’d expect from this label, and Honeck’s detailed sleeve notes are well worth reading.

Steffen Wolf: Essais Musicaux - works for violin, clarinet and piano (TYXArt)

Steffen Wolf: Essais Musicaux - works for violin, clarinet and piano (TYXArt)

Sometimes what doesn't get said is just as important as what does, occasionally even more so. Essais Musicaux is a collection of new compositions by Hamburg-based composer, singer and singing teacher Steffen Wolf (b.1971). The booklet gives copious accounts and illustrations of the tantalisingly wide range of extra-musical things that have inspired him to compose the sequence of relatively short pieces (six collections, a total of fifty-one tracks) which appear on the CD. So what does get said is that Wolff has been variously moved to write music by (deep breath): his wife’s paintings...some memories his own childhood inspired by an old photograph...the Abbey at St.Philibert in Burgundy... the passing seasons as witnessed by chestnut trees... the haikus of Kobayashi Issa...and the poetry of a towering figure in the literature of the German enlightenment, Christoph Martin Wieland. It really is quite some list.

But what is not discussed anywhere – with the exception of mentioning that he has quoted a couple of motifs from Hildegard von Bingen – is where his musical inspiration comes from. Where are we then, musically speaking? I would say somewhere in a post-tonal world where Berg, Ravel, Stravinsky, Bartok and Messiaen are the resident deities. The pieces are generally brief, even epigrammatic, with only two tracks extending beyond three minutes. This seems to fit with another preoccupation of Wolf’s which has been to adapt the methods of Niccolo Vaccai (1790-1848) to the German Lieder repertoire – his work in this area has been published by Breitkopf. So just as Vaccai and now Wolf require the budding singer to forget learning via studies or exercises, but to find her or his way straight into the atmosphere of songs, so the German’s preoccupation as composer seems to be to keep landing the performer (and the listener) instantly into a new mood, a fresh and different place.

Take the first and the last pieces of the St Philibert set. Wolf chooses to needle-drop us in a world where a piano (Jennifer Hymer, characterful and well recorded) is imitating bells. There is dark foreboding in the air – and, just like the opening of Ravel’s “Le Gibet” from Gaspard de la Nuit, the bells happen to be in B flat. Take “Grad’ heut Morgen” for solo clarinet from the “Kreise” set. Here a lonely clarinet (fantastic control from Pamela Coats) seems to be referencing the “Abîme des Oiseaux” from Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time. While there is certainly a wide range of moods and inspirations here, I am left with the thought that Wolf's process of composing - and his magpie instinct - feel antithetical to sustained listening. That said, TyxART, as ever, are a class act: they set extremely high standards with both the recording and the accompanying materials. Sebastian Scotney

Striggio: Mass in 40 Parts I Fagiolini (Coro)

Striggio: Mass in 40 Parts I Fagiolini (Coro)

Benevoli: Missa Tu Es Petrus I Fagiolini (Coro)

I’m on a bit of an I Fagiolini jag at the moment. I recently covered for theartsdesk their storming one-to-a-part Monteverdi Vespers at Kings Place and can now share my enjoyment of a pair of recent album releases. One is a brand-new recording while the other is a re-master of a 2011 disc, but both exhibit the classic I Fagiolini traits of being attention-grabbing and top-quality performances of undeservedly obscure repertoire. The re-master is of the ground-breaking recording of Striggio’s 40-part motet and mass, Missa Ecco sì beato giorno, alongside Thomas Tallis’s much more celebrated Spem in Alium. As the booklet has it, “Tallis’s masterwork, is simultaneously a tribute to Striggio and a determined effort to upstage him” – the legend being that Striggio’s piece was heard during his visit to England, prompting the Duke of Norfolk to challenge England’s composers to prove their worth by outdoing it. Step forward Tallis, and the rest is history (or, possibly, myth).

The Striggio was lost till this century, until re-discovered and realised by Davitt Moroney, with I Fagiolini making this first recording. It is an impressive compositional achievement – no one had paved the way for Striggio, and writing in 40 parts is not easy – but it must be said it isn’t a patch on the Tallis, who is more adventurous both harmonically and texturally. Robert Hollingworth made the decision to characterise the different choral sub-groupings (in both Striggio and Tallis) with different instrumental doublings – which he maintains is an authentic reading, and that the modern purely choral Spem is a later development. The result is a richer and more colourful sound and I for one am a sucker for a bit of cornett. There is very much an A-Team of performers, both instrumental and vocal, on duty, and the result is unsurprisingly a complete treat. I’d really love to hear it live, but that’s not likely any time soon, given modern budgets. The re-mastering has apparently beefed up Choir V in the Striggio and brought out more detail: it certainly sounds terrific and in putting Spem in context only makes it seem even more extraordinary.

The new recording is centred around the colossal polychoral Missa Tu es Petrus by Orazio Benevoli (1605-72), a result of Robert Hollingworth “rooting around” for undiscovered 17th music worth breathing new life into. As he says, “some music is better left in libraries… [but] Benevoli’s is quite spectacularly not one of those pieces.” It is based on a Palestrina motet, which kicks off the album, and is great, in a Palestrina-ey way. Benevoli then takes it in all sorts of new and unexpected directions, with an inventiveness and boldness that makes it surprising he isn’t much better known. It’s a rich and rewarding piece and kudos to Hollingworth for having uncovered it. The multi-choir textures are as rich as a Roman banquet, producer Adrian Hunter capturing a remarkable depth of sound. The personnel has some overlap with the Striggio group, plus some younger voices, and as on the earlier record the voices are reinforced with a selection of brass, strings and the glorious dulcian. Bernard Hughes

The new recording is centred around the colossal polychoral Missa Tu es Petrus by Orazio Benevoli (1605-72), a result of Robert Hollingworth “rooting around” for undiscovered 17th music worth breathing new life into. As he says, “some music is better left in libraries… [but] Benevoli’s is quite spectacularly not one of those pieces.” It is based on a Palestrina motet, which kicks off the album, and is great, in a Palestrina-ey way. Benevoli then takes it in all sorts of new and unexpected directions, with an inventiveness and boldness that makes it surprising he isn’t much better known. It’s a rich and rewarding piece and kudos to Hollingworth for having uncovered it. The multi-choir textures are as rich as a Roman banquet, producer Adrian Hunter capturing a remarkable depth of sound. The personnel has some overlap with the Striggio group, plus some younger voices, and as on the earlier record the voices are reinforced with a selection of brass, strings and the glorious dulcian. Bernard Hughes

The Resonance Between Del Sol Quartet, with Alam Khan (sarod), Arjun K Verma (sitar) and Ojas Adhiya (tabla)

The Resonance Between Del Sol Quartet, with Alam Khan (sarod), Arjun K Verma (sitar) and Ojas Adhiya (tabla)

I’ve noticed a spike in unusual string quartet albums, and here’s another one. This release’s press notes mention the word "fusion" and the list of creative and technical collaborators who worked on it is alarmingly long. I needn’t have worried: this meeting between San Francisco’s Del Sol Quartet plus Alam Khan and Arjun J Verma on sarod (a lute-like instrument) and sitar respectively is consistently entertaining. Khan and Verma collaborated with composer Jack Perla to create the ten pieces here, one issue being how to reconcile, harmonically, traditional Indian instruments with a western string quartet. Making tiny intonation adjustments isn’t a problem for string players, and the Del Sol musicians blend seamlessly with their partners. Covid restrictions meant that the players had to record their parts separately, though the results sound incredibly natural with engineer Neil Godbole deserving a shout out – I’d recommend listening to The Resonance Between on headphones.

“Awaken” makes for a striking opener, the antiphonal violin lines soon joined by table, sarod and sitar, and listen our for Ojas Adhiya’s chugging table rhythms at the start of “Embark”. A glorious sarod solo at the start “The Passage” sent me down a YouTube rabbit hole in search of other examples. It’s a little frustrating that the sleeve notes don’t explain the significance of track titles, and I’m assuming that “Two Worlds” refers to the mixture of musical traditions. The closer, “The Moon and the Mountain”, plays out like a mini-tone poem.

Add comment