Imants Kalniņš: Complete Symphonies and Concertos Liepāja Symphony Orchestra/Atvars Lakstīgala and Māris Sirmais (Skani)

Imants Kalniņš: Complete Symphonies and Concertos Liepāja Symphony Orchestra/Atvars Lakstīgala and Māris Sirmais (Skani)

If the eye-catching box design doesn’t attract your attention, the first track on CD 1 will, an extract from the veteran Latvian composer Imants Kalniņš’s 1973 score to the popular Latvian film Blow, Wind. Based on a folk song and lushly orchestrated, it could pass for a slice of Vertigo-era Bernard Herrmann, at least until the electric guitar solo starts. It makes for a perfect appetiser. Skani haven’t arranged Kalniņš’s seven symphonies in chronological order, so to hear his 1964 Symphony No. 1 you’ll have to switch discs. A sombre, large-scale work owing a debt to Shostakovich, the gaudy, ambiguous apotheosis both chills and thrills. Kalniņš' gift for widescreen melody asserts itself again in the follow-up from a year later. At times you’re reminded of Malcolm Arnold. Spikiness and sweetness co-exist, as when the slow movement’s austere chorale segues into a melting flute tune.

Symphony No. 3 is smaller in scale and quirkier, supposedly prompted by Kalniņš’ colleague Arvo Pärt suggesting that he compose “the craziest thing he could think of” and producing a sequence of five pungent, balletic miniatures. There’s some brilliant percussion writing in a 1966 Concerto for Orchestra, composed shortly before Kalniņš founded the band 2XBBM, playing keyboards until state interference forced the group to split. There’s a selection of their songs on YouTube, and a recycled 2XBBM ballad appears in the opening movement of Symphony No. 4, accompanied by electric bass and drum kit. Kalniņš’s finale originally set texts by US poet Kelly Cherry but the Soviet authorities refused to sanction a performance until an instrumental transcription was provided. It’s a bold, accessible work, played with punch and panache by the Liepāja Symphony Orchestra under Atvars Lakstīgala, sharing conducting duties across the cycle with Māris Sirmais.

No. 5 begins with dark, restless energy and closes in a mood of chilly resignation. Over 20 years separate it from its successor, during which time Kalniņš became involved in the push for Latvian independence and was elected to the state parliament in the early 1990s. Symphony No. 6 is an epic musical response to Latvia’s recent history. The two choral movements contain some exquisite music, but the work feels overstretched. No. 7, completed in 2015 is concise, lyrical and engaging. Kalniņš’ Cello and Oboe Concertos, both enjoyable, are thrown in, plus an appealing miniature written in the same year for a Latvian National Theatre production. I’m now a fan – it’s a treat to encounter a hitherto unknown composer with such a distinctive and likeable personality. I’ve been dipping in and out of this box for months, and I’m still discovering things to marvel at. The performances are committed and beautifully recorded. A winner.

Bach: Cello Suites for Solo Piano, transcribed and performed by Eleonor Bindman (Grand Piano)

Bach: Cello Suites for Solo Piano, transcribed and performed by Eleonor Bindman (Grand Piano)

The indestructability of Bach’s music is one of its joys; good arrangements and transcriptions don’t dilute the music’s essence, its Bachness. Eleonor Bindman was prompted to make her own versions of the six Cello Suites after exploring interventionist arrangements by Silotti, Raff and Godowsky. She makes an interesting comparison between a pianist tackling, say, a solo violin partita, where supporting harmonies can be discreetly added in the left hand, and the near-impossibility of doing the same thing with a cello line. Bindman has changed very little: tempi are on the swift side, and the articulation is more pianistic. If you didn’t know the cello originals, you’d happily accept these as keyboard suites. Suite No. 3 is especially good, the prelude’s opening flourish spectacular in Bindman’s hands, with a beautiful, squelchy final cadence. The “Sarabande” in Suite No. 5 is dark and probing, the suite’s “Gigue” sharp and angular. No. 6’s opening zips along like a dance movement, the repeated D’s so different in character played at this speed. Fascinating, and fun; Bindman’s scholarly but readable notes seal the deal, and the recording is excellent.

Zachary Carrettin’s Metamorphosis features Suites 1-3 played on viola. Carrettin’s bright, warm tone is appealing and Bach’s dance movements have energy and grace aplenty. Suite No. 1’s “Courante” and “Gigue” are outpourings of uninhibited joy, as are the equivalent movements in Suite No. 3. Suite No. 2 is a study in melancholy elegance, with another peerlessly played “Saraband”. And do listen out for Carrrettin’s highly effective pizzicato da capo in the “Menuett”. The disc boasts spectacularly vivid and lifelike sound; let’s hope that we get a second volume before too long.

Zachary Carrettin’s Metamorphosis features Suites 1-3 played on viola. Carrettin’s bright, warm tone is appealing and Bach’s dance movements have energy and grace aplenty. Suite No. 1’s “Courante” and “Gigue” are outpourings of uninhibited joy, as are the equivalent movements in Suite No. 3. Suite No. 2 is a study in melancholy elegance, with another peerlessly played “Saraband”. And do listen out for Carrrettin’s highly effective pizzicato da capo in the “Menuett”. The disc boasts spectacularly vivid and lifelike sound; let’s hope that we get a second volume before too long.

Molly Herron – Through Lines (New Amsterdam)

Molly Herron – Through Lines (New Amsterdam)

Is this a Picforth revival? Only one composition by him survives, an "In Nomine" from the 1580's. And yet, out of all the glorious wealth of repertoire for viols, it is that solitary piece which not only served as the jumping-off point for a recent album of 21st century music for viols by various composers from Liam Byrne, Concrete (Bedroom Community, 2019). It has just cropped up again. This Englishman, about whom there seems to be not a single biographical clue anywhere, is the only composer to be referenced in this new album of pieces for three and four viols by New Hampshire-born composer Molly Herron, Through Lines. Herron says she has taken what she calls Picforth's "conceit" and transformed it into an "alternate polyrhythmic landscape". Herron, with a recent doctorate from Princeton – where this album was recorded, with gamba players Loren Ludwig, Zoe Weiss, Kivie Cahn-Lipman from Science Ficta – now has a professorial post at Vanderbilt in Nashville. The biography on her website sets out the context: “Composer Molly Herron 'thinks deeply about motion, energy, and the physics of sound'.” And there is plenty of evidence of that on the new disc, particularly in the “Interludes”, on which Herron herself plays a fourth bass viol part. “Interlude 1”, for example, plays with half-lit natural harmonics over a drone. “Interlude 3” is a short essay in scrunching microtones. Elsewhere there are gestures which suggest a pervasive influence of minimalism. “Canon No.2” in particular seems to want to relate to Tudor music but to see it (pun unavoidable) through the prism of Philip Glass.

The vibe is experimental, but in a cautious, often tentative way, and particularly so when contrasted with the more extrovert and performative Byrne disc. Both the opening track “Canon 3” and the closer “Hammer and Pull” find their featherlight endings at the borders of pin-drop silence. New Amsterdam is a fascinatingly eclectic Brooklyn-based label, and it is good that they have found this music on one of the quietest of by-ways in contemporary music, bringing it to our attention in such a thoughtful and informative way. And maybe this disc will also send some new listeners back to explore the many glories of the repertoire for viols beyond Picforth, from the deeply affecting “Lachrimæ” of Dowland and the dancing joy of the “Ayres” of Tobias Hume through to the irresistible lyrical grace of the "Pavans" of Ferrabosco the younger and the sublime elegance of the “Tombeaux” of Marin Marais.

Sebastian Scotney

Miloš Karadaglić: The Moon and the Forest (Decca)

Miloš Karadaglić: The Moon and the Forest (Decca)

There’s a telling line in Joby Talbot’s introduction to his Ink Dark Moon, with guitarist Miloš Karadaglić describing how dispiriting it is to see half the orchestra schlep offstage each time he’s about to perform a concerto. Talbot uses a larger orchestra than usual, with Miloš discreetly amplified. Balance issues don’t arise, and, unusually, the guitar can be heard properly by the orchestral players. If you’ve enjoyed Talbot’s ballet scores, you’ll admire this subtle and likeable work. Melodically rich and texturally interesting, it has a nicely ruminative central slow movement, and the crowd-pleasing pay-off is fun. This studio recording, made with Ben Gernon and the BBC Symphony Orchestra some months after they gave the 2018 Proms premiere, is very well engineered, the balance issues noted in theartsdesk’s review never arising.

The other commission here is Howard Shore’s The Forest, also a large-scale concertante work. Though beautifully performed and recorded, Miloš here accompanied by Ottawa’s National Arts Centre Orchestra under Alexander Shelley, it’s curiously diffuse, sounding too much like agreeably woozy background music. Two solo guitar encores are thrown in, including an effective transcription of Schumann’s “Traumerei”. Buy this for the Talbot.

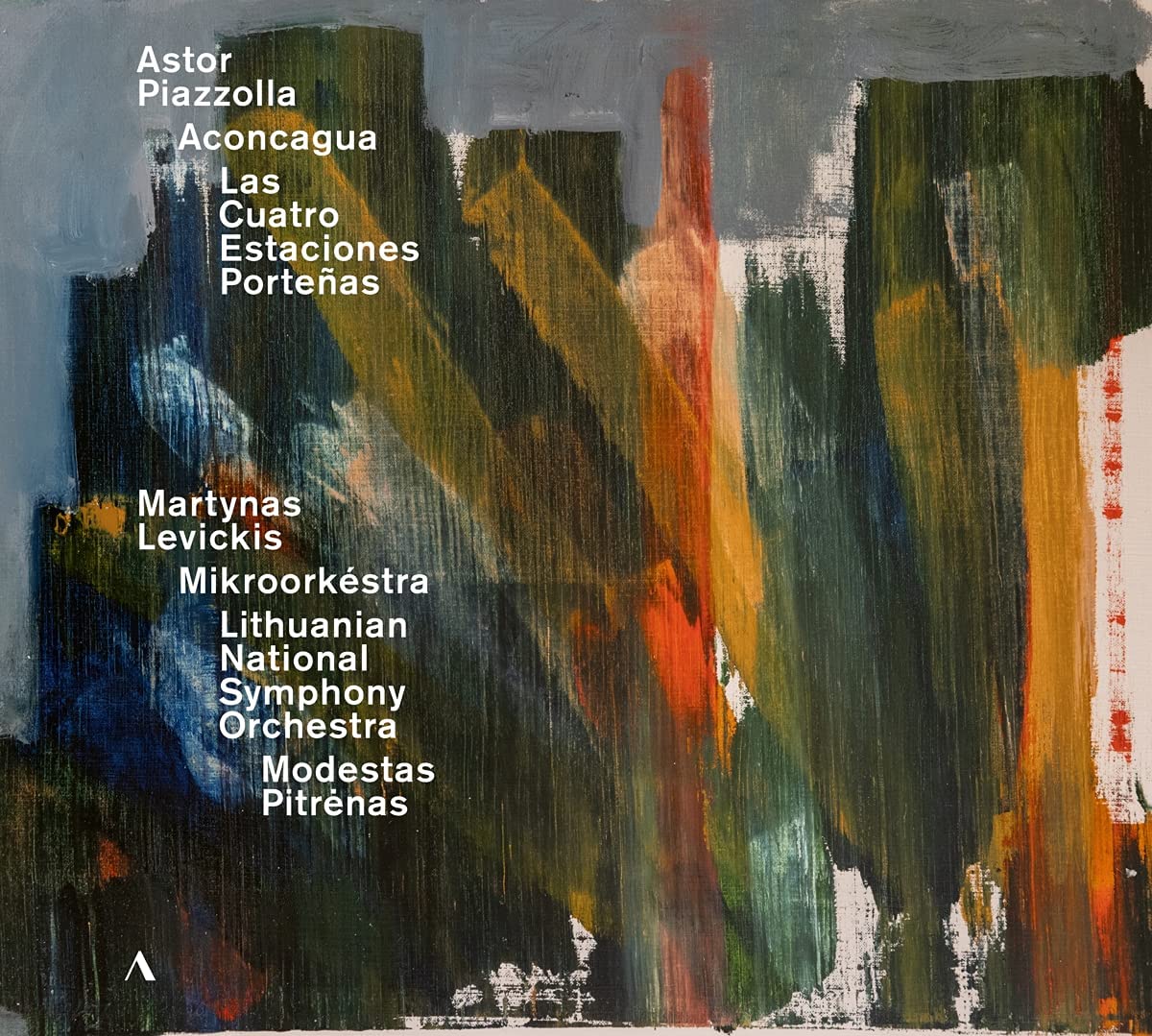

I've a swathe of CDs in the to-review pile issued to celebrate the centenary of the great Argentinian bandoneon player Astor Piazzolla. Here are two to begin with. Neither is strictly authentic, but both sound idiomatic through staying faithful in spirit to Piazzolla's idiom. He was an erudite, technically skilled musician who spent several years studying with Nadia Boulanger in Paris. Rather like Ravel's famous advice to Gershwin, Boulanger encouraged Piazzolla to keep on writing tangos whilst developing his contrapuntal skills. Martynas Levickis plays Piazzolla's Concerto for Bandoneon and Las Cuatro Estaciones Porteñas on the Accentus label – on accordion rather than bandoneon. The latter work is usually heard in Desyatnikov's arrangement for solo violin and orchestra; Levickis gives us a slightly expanded version of Piazzolla's chamber original, accompanied by his Mikroorkéstra ensemble. It's a terrific performance, full of bite, tutti strings and piano really digging into the start of the "Summer" movement. Piazzolla's Bandoneon Concerto is a modern classic. Levickis's accordion sounds dark and rich in this live recording, an asset in the sultry slow movement, and the finale's coda has huge impact here, accompanied by the Lithuanian National Symphony Orchestra under Modestas Pitrenas.

I've a swathe of CDs in the to-review pile issued to celebrate the centenary of the great Argentinian bandoneon player Astor Piazzolla. Here are two to begin with. Neither is strictly authentic, but both sound idiomatic through staying faithful in spirit to Piazzolla's idiom. He was an erudite, technically skilled musician who spent several years studying with Nadia Boulanger in Paris. Rather like Ravel's famous advice to Gershwin, Boulanger encouraged Piazzolla to keep on writing tangos whilst developing his contrapuntal skills. Martynas Levickis plays Piazzolla's Concerto for Bandoneon and Las Cuatro Estaciones Porteñas on the Accentus label – on accordion rather than bandoneon. The latter work is usually heard in Desyatnikov's arrangement for solo violin and orchestra; Levickis gives us a slightly expanded version of Piazzolla's chamber original, accompanied by his Mikroorkéstra ensemble. It's a terrific performance, full of bite, tutti strings and piano really digging into the start of the "Summer" movement. Piazzolla's Bandoneon Concerto is a modern classic. Levickis's accordion sounds dark and rich in this live recording, an asset in the sultry slow movement, and the finale's coda has huge impact here, accompanied by the Lithuanian National Symphony Orchestra under Modestas Pitrenas.

Ksenija Sidorova's Piazzolla Reflections (Alpha Classics) also includes the concerto, played again on accordion. Her studio performance is better balanced and slightly tauter than Levickis's, Thomas Hengelbrock's Elbphilharmonie offering brilliant support. Six shorter Piazzolla numbers are also thrown in, including a punchy version of "Libertango" almost swamped by an over-elaborate orchestral backing. Franck Angelis's Fantasie on a theme of Piazzolla "Chiquilin de Bachin" taps into the original's melancholy, and there's an enchanting Bach slow movement. Most striking is Sergey Akhunov's Two Keys to One J. Brodsky's Poem, Sidorova and the Goldmund Quartet effortlessly catching the changing moods. She's due to perform on the Last Night of this year's Proms. Do tune in – she's great.

Ksenija Sidorova's Piazzolla Reflections (Alpha Classics) also includes the concerto, played again on accordion. Her studio performance is better balanced and slightly tauter than Levickis's, Thomas Hengelbrock's Elbphilharmonie offering brilliant support. Six shorter Piazzolla numbers are also thrown in, including a punchy version of "Libertango" almost swamped by an over-elaborate orchestral backing. Franck Angelis's Fantasie on a theme of Piazzolla "Chiquilin de Bachin" taps into the original's melancholy, and there's an enchanting Bach slow movement. Most striking is Sergey Akhunov's Two Keys to One J. Brodsky's Poem, Sidorova and the Goldmund Quartet effortlessly catching the changing moods. She's due to perform on the Last Night of this year's Proms. Do tune in – she's great.

Add comment