Malcolm Arnold: Symphonies 1-9 London Symphony Orchestra/Richard Hickox, BBC Philharmonic/Rumon Gamba (Chandos)

Malcolm Arnold: Symphonies 1-9 London Symphony Orchestra/Richard Hickox, BBC Philharmonic/Rumon Gamba (Chandos)

Malcolm Arnold's lasting reputation as a chameleonic comedian endures, though his more overtly serious cycle of nine symphonies shouldn't be overlooked. They span his compositional career – the bracing, bold No. 1 written in 1949, the alarming, sepulchral 9th completed in 1986. They exist in a very British parallel musical universe, miles from the European avant-garde. But Arnold wasn't an insular composer; these symphonies make overt reference to Berlioz, Sibelius, Shostakovich and Mahler. And it's Mahler who comes to mind most often, notably with regard to Arnold's habit of juxtaposing jauntiness with gloom. There's a good deal of surface brilliance here: at his best, Arnold was a phenomenal orchestrator and a shrewd organiser of his material. The contrapuntal writing is immaculate, the frequent fugues unfolding with matchless skill. The fluency dazzles. Listen closely and you'll hear hints of desperation and ambivalence, though Arnold could rarely resist writing Hollywood endings. Symphonies 1-4 all end brightly, though not without some struggle. No. 2's rapt, painful slow movement is marvellous.

Things take a more serious turn with the 5th – its shadowy first movement a musical memorial to recently deceased friends (including Dennis Brain and Gerard Hoffnung). The symphony's close is staggeringly bleak, the glowing big tune disintegrating before the work's abrupt ending. No. 6's pleasures include a magnificent, taut opening – flickering wind solos and whooping horns over a jazzy bass line. No. 7's violence is shocking, particularly a disturbing passage where lyrical strings get squashed by a burst of raucous Dixieland jazz. It's all too tempting to hear this music's crazy bipolarity as a reflection of Arnold's own troubled state of mind. No. 8 does finish optimistically, but the 9th is the toughest nut to crack – 48 minutes of spare counterpoint, the slow finale's exhausted, calm resolution an oddly disquieting end to one of the most entertaining series of symphonies you'll hear. Richard Hickox and the LSO are on fine form in the first six, and Rumon Gamba's BBC PO don't disappoint in the fiendishly difficult later works.

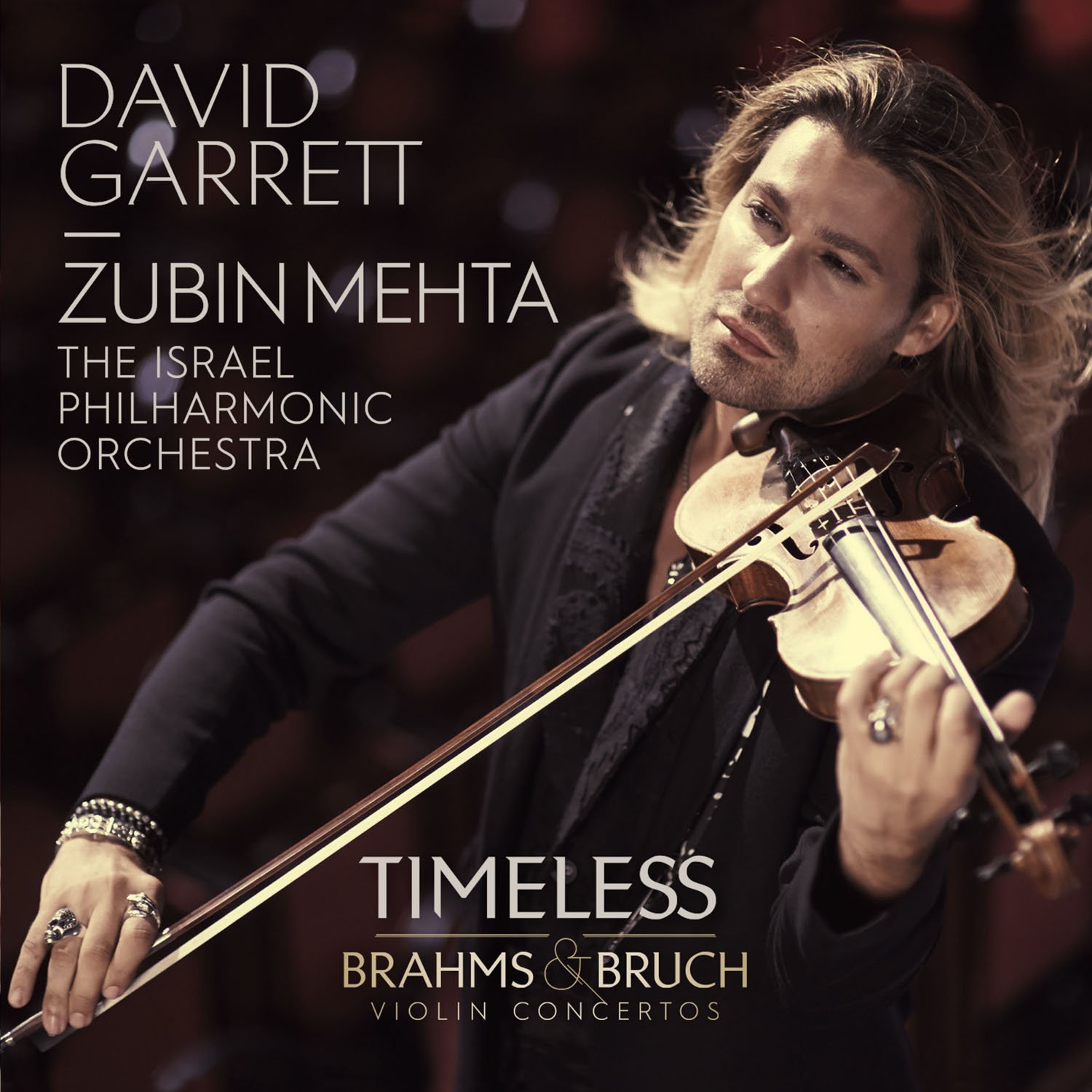

Brahms & Bruch: Violin Concertos David Garrett (violin), Israel Philharmonic Orchestra/Zubin Mehta (Decca)

Brahms & Bruch: Violin Concertos David Garrett (violin), Israel Philharmonic Orchestra/Zubin Mehta (Decca)

David Garrett's name is far more prominent on this release's cover than those of Brahms and Bruch. Not good. However, Zubin Mehta writes in the booklet of his hopes “that this CD will help David's other public, the crossover public, to also listen to Brahms and Bruch.”, and the interview with Garrett in the booklet suggests that he does know his stuff. It's too easy to be snobbish about crossover artists. I retain a sneaking fondness for Lang Lang – anyone who's prompted millions of children to take up the piano deserves some respect, not sneering. Garrett's image won't be to everyone's taste, but no one's forcing you to buy his albums or watch the videos.

So, should you throw out your Oistrakh and Szeryng LPs? Not yet, but, in a fiercely competitive field, these performances have a lot to offer. Garrett's tone is rich, and his intonation is flawless. The faster movements come off beautifully: the finale of the Brahms is a blast and there's an appealing sincerity and gutsiness to the Bruch's Allegro moderato. Mehta's Israel Philharmonic provide well-upholstered support – the woodwind intro to the Brahms slow movement is matchless. It's the reflective moments which don't always deliver, with Garrett occasionally sounding as if he's trying a little too hard. Highly enjoyable though, and Decca's recorded sound has plenty of warmth.

Hartmann: Simplicius Simplicissimus Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra, Netherlands Radio Choir/Markus Stenz (Challenge Classics)

Hartmann: Simplicius Simplicissimus Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra, Netherlands Radio Choir/Markus Stenz (Challenge Classics)

Maarten Brandt's sleeve essay wonders how Karl Amadeus Hartmann's music might have developed had he not been living in 1930s Germany. Though his output wasn't actually forbidden by the Nazis, Hartmann refused to allow public performances, retreating instead into what he termed "inner emigration". His breezy neoclassical style darkened, his music instead paying overt homage to composers banned by the regime. The opera Simplicius Simplicissimus was completed in 1936, an adaptation of a sprawling picaresque novel set during the Thirty Years War. Stark anti-war sentiments are mingled with autobiographical elements, notably in the character of the hermit whose retreat from society mirrors that made by the composer. Hartmann's music can be a tough listen, but it's invariably superbly crafted and emotionally powerful; anyone who's responded to his symphonies will find much to admire here. Get past the snarling, percussive exterior and there's much that's gravely beautiful. Typical is the close of Act 1, its anguished, Bergian string writing fused with a Bach chorale. There are some lighter moments: the spiky, neo-classical dances at the start of the third act wouldn't disgrace Weill or Eisler.

Challenge Classics' live recording was taped in the Concertgebouw during the same concert series which produced their cycle of Hartmann symphonies. Markus Stenz and his superb Netherlands Radio Philharmonic relish the dense orchestral writing, whilst never obliterating the vocals. Soprano Juliane Banse as Simplicius copes magnificently with Hartmann's angular vocal lines and Will Hartmann is a sympathetic Hermit. The villainous Governor is creepily portrayed by tenor Peter Marsch. A fascinating, haunting work, a major 20th-century opera by an underappreciated composer. Good notes, and a brief synopsis is provided. But, frustratingly, the libretto is only printed in German, and my attempts to find a translation online drew a blank.

Add comment