theartsdesk Q&A: Conductor Markus Stenz on Mahler | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Conductor Markus Stenz on Mahler

theartsdesk Q&A: Conductor Markus Stenz on Mahler

Let's make a symphony - a very big one. Live-wire German interpreter explains his own special approach

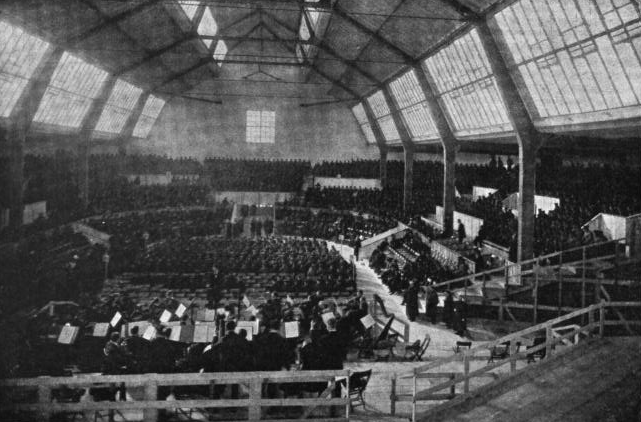

Never mind the huge interpretative challenges; Mahler’s Eighth, dubbed the "Symphony of a Thousand" owing to the gargantuan forces the composer marshalled as conductor of its 1910 Munich premiere, needs an even greater mastery of logistics.

The answer came in a performance to mark 25 years of one of the world’s best concert halls, the Cologne Philharmonie, which took flight from the start and culminated in one of the biggest long-term ecstasy bursts I’ve ever experienced in a concert hall. Graham Rickson reviews the live recording for the German label Oehms Classics over on this week’s classical roundup. I met Stenz the morning after one of the performances to discuss the whys and wherefores as well as how his early days covering contemporary repertoire with the London Sinfonietta had affected what he does now, and why Mahler remains the greatest.

DAVID NICE: So this was the first time you’ve tackled the Eighth in your home city.

MARKUS STENZ: Yes – and the third time in my life. Every once in a while, probably once in a decade, I can have a go at it. The other outings were at the New Zealand Festival in 1996, and next with my then orchestra the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra. We made a rather wonderful celebratory performance to mark 100 years of the Australian parliament, which sat for the first time in Melbourne, so we made a point of playing Mahler 8 in that same building, one of those big Victorian halls and I think we had 6000 people in the audience alone.

I wondered whether there was ever an option to perform it in Cologne Cathedral. Gergiev and the London Symphony Orchestra chose St Paul's as the venue, and acoustically it was a disaster, though Radio 3 turned it into a performance you could hear.

I wondered whether there was ever an option to perform it in Cologne Cathedral. Gergiev and the London Symphony Orchestra chose St Paul's as the venue, and acoustically it was a disaster, though Radio 3 turned it into a performance you could hear.

So you got the virtual reality – no-one heard it in real life, but it was all there in the broadcast! No, I wouldn't even think of doing it in a cathedral, I don’t think it’s a piece for it. It needs to be carefully tailored to the venue. It's worth looking back at Mahler’s meticulous preparation for the first performance when Alfred Roller, his favourite stage designer at the Vienna Court Opera, came up with a layout of the stage in the big Munich venue, so that the music could work. There is a fascinating photo of that first performance (pictured above right) where you can see how the masses are disposed – he had almost 450 more people than we had last night. So tailoring it was our first step with the Philharmonie [Cologne's Philharmonic Hall]. We had as a point of reference the previous performances that had been done in the Philharmonie including the opening concert 25 years ago conducted by [Marek] Janowski, and you see the photos there and how they did it, and we went for a distinctly different approach in that we extended the platform, we pushed the orchestra closer to the audience and thus created the space for an extra 100 singers, ladies’ voices, on stage.

Did that involve taking out some of the stalls?

Yes. It did, and that was the first outing of that stage in a classical concert in the Philharmonie. And even the Philharmonie didn’t know that possibility existed until it was created. I think they had used something similar to this for the run of a ballet performance beforehand, so we knew it could be done, however it still felt it was purpose built. Other big questions: where do you put the choruses, where do you place the children, what kind of string strength - we played it with ten double basses.

Would you normally have them ranged along the back?

Yes. I love the fact that when everyone is connected with the bass, the intonation is instantly good.

And in Mahler it’s especially important.

It’s vital. And I love splitting the brass. I love the horns to the left and trumpets and trombones to the right, trumpets and trombones not playing direct to the audience but making a more indirect sound and then the double bass and the woodwind body reigning the harmonic world. And I think one must have Mahler with firsts and seconds [violins] playing antiphonally, because that’s the way he heard it, he conceived it in every score and every picture.

That tends to be the rule now rather than the exception.

I wouldn’t necessarily be as strong minded as that unless it’s Mahler. But I know that seating also works very well for Strauss and Elgar...

And the idea to have the soloists further back than the orchestra?

There are a number of reasons. First I do think for the ensemble it’s much better. I can be in touch with them and they with me, and that line-up with eight soloists singing simultaneously, you get those funny looks to the conductor or something that’s not under control. Probably the least valid reason is that I didn’t want to run the risk of an unknown position in the Philharmonie for the singers, because you know with the stage extension, they would have ended up in a slot for which the hall was not designed. We’ve pushed the orchestra out further. So I couldn’t really be sure that the singers would be carrying, that their sound would be out there. That brings me to reason no. 3 – I believe that wooden back wall right behind them is an excellent enhancer of their voices, it helps them.

Then reason no. 4, probably the most fascinating one from a balance point of view:when everyone in the orchestra can hear the singers then they are responsible for the balance too. When they can only see the backs of the singers, they have no way of judging whether they’re playing too loud, really accompanying, is this becoming chamber music or not. And the Gürzenich Orchestra plays 160 nights at the opera every year [in 2004 Stenz became Chief Music Director of the City of Cologne, which made him head of the opera house too] is very accustomed to breathing with the singers and listening, and accompanying. So it's a case of all these reasons combined, almost inevitably suggesting the singers be centre stage, supported by the back wall, carried by the orchestra and embedded in the choir.

It’s interesting, because the first movement [the setting of the Pentecostal Hymn 'Veni Creator Spiritus] is like a unified statement from everyone, and the second [setting the final scene of Goethe's Faust] is like a Wagner act.

If you want, it’s very theatrical. I almost like to think of it as a song cycle because rather than something which cries out for staging, it’s all in the imagination. And therefore you just need the music to create the right aura, the right feel, and then it all takes off in your own mind.

Did you work really hard with them on the projection of the text? It came over very vividly, especially with the tenor Brandon Jovanovich.

Oh, that’s brilliant. Yes with him I did work a lot, I first met him in Chicago two years ago and I immediately thought that’s the voice I’d like to hear in Mahler 8 . We were doing [ Janáček's] Katya [Kabanova], – and he struck me as someone who’s extremely well trained to come up with the consonants, you know how in Czech you have to spit them out left, right and centre.

Yes, he was in the first run of Rusalka at Glyndebourne.

You know, I also met Orla [Boylan, second soprano in the performance, pictured right on the night of the performance] at Glyndebourne working on Jenufa, and we've done that here as well as The Marriage of Figaro, when she sang the Countess.

You know, I also met Orla [Boylan, second soprano in the performance, pictured right on the night of the performance] at Glyndebourne working on Jenufa, and we've done that here as well as The Marriage of Figaro, when she sang the Countess.

She has such a fantastic presence, I was asking her last night whether anyone had taught her just how to walk on to a platform because it’s so commanding. She said she wished someone had, but it’s just innate.

Which is even better, because it’s natural. It’s totally her, totally authentic.

She said last night you wanted a different kind of voice for the "role" of Gretchen/Una Poenitentium in the second movement from second soprano in the first movement, who normally sings both, that's the first time I’ve heard four sopranos.

Well, there's always various factors to be taken into account: in our Mahler cycle we somehow made a commitment to Christiane Oelze for the songs from Des Knaben Wunderhorn and the Fourth Symphony and therefore when checking up in the Eighth we found only the Una Poenitentium/Gretchen music was suitable. We went back and forth and finally said OK, we could think of it as yet another colour just like the Mater Gloriosa is yet another colour, and in thinking about this song cycle part two, you get the individual voices of men and women, and then you get a new voice, Gretchen, a personality with a name.

It’s lighter..

Exactly – increasingly lighter. And so that’s how we did it, and I’m very happy with that decision. I don’t think it’s a must, it was more or less a bonus, a luxury indulgence.

In the first movement the second soprano is more like a Verdi lirico spinto, and at the end as well, where there are big phrases for both first and second sopranos.

Well, I think that especially played itself out rather beautifully.

Did you feel that sense as a conductor – I know it has to be in control – but did you feel something special going on last night from the pianissimo entry of the chorus to the end, or does that always happen in performance?

It doesn’t always happen, I don’t think it’s foolproof, it’s something and it should always remain something special, and I love the fact that if you put in enough care, with all those choices, the choirs, soloists, rehearsal time, that culminating sequence can become magical. I think it’s incredibly hard work for the choir, they have to sing softly and also for the sopranos, big dramatic voices that you cast for Part One, can’t necessarily float above the choir as well as Orla did, and all those components combined last night. From my perspective, I shouldn’t really say this, but this necessity to remain in control, this incredible focus that’s needed for that, doesn’t allow me to melt. If I end up in a situation of emotional meltdown,, it just can’t work any more. It’s a different perspective from the audience

Nevertheless I find that interesting because I remember Stéphane Denève saying that there was one point where he almost lost consciousness of where he was, in the middle of [Debussy's] Pelléas [et Melisande]. That really struck me, I never thought a conductor would do that.

Oh, there are overwhelming moments, and there are performances where I cannot honestly say what went on, because it was just so in the moment, and it is a profession that tries to generate the perfect moment. We all have a game plan, we all have the input time when we sit down with the score and say, this is the way it must go, but come the performance what you want to create is a moment with no past and no future, and it’s always awesome when that happens, and sometimes you can feel it, sometimes the spark of the performance hits the audience as well.

Oh, there are overwhelming moments, and there are performances where I cannot honestly say what went on, because it was just so in the moment, and it is a profession that tries to generate the perfect moment. We all have a game plan, we all have the input time when we sit down with the score and say, this is the way it must go, but come the performance what you want to create is a moment with no past and no future, and it’s always awesome when that happens, and sometimes you can feel it, sometimes the spark of the performance hits the audience as well.

Were you aware of the audience being so attentive last night?

Yes [emphatic]

The way you held the silence at the end of the colossal first movement, and the way the silence carried on in the pause between the two movements...

But it needs that, doesn’t it, it needs that time…

In the Albert Hall they’d all have applauded, because Proms audiences now tend to at the ends of movements.

Oh, the Albert Hall is divine, it’s absoloutely stupendous. I love that place, and I love it for the fact that it allows for the subtleties too. I remember from my [London] Sinfonietta days when we did late night Proms and sometimes there were only five performers on stage, and they would play softly, but nevertheless it would fill the hall.

You’re right, it draws you in. The best thing I heard in the hall in 2011 was a folk singer, admittedly amplified, June Tabor, in a late night Grainger concert. A solo piano can achieve something similar.

Interesting. It’s all possible. And it takes some courage. I remember when the Gürzenich played their debut at the Proms, Mahler Fifth in 2008, the courage, the orchestra in the dress rehearsal really needed to develop some trust to really search for the soft sounds, and trust the pianissimo to carry.

I think it’s Barenboim who said you mustn’t reach out, you mustn’t force, you must let your audience come in to you, which is a good way of putting it. The hall is terrible in many respects. I was talking to some Artek acousticians recently, thinking they would find it an abomination, but they’re just so fond of it, because it’s a unique place.

It is absolutely unique.

And you can do things there you wouldn’t do anywhere else. Plus just to see 6000 people in itself is amazing.

That’s what music is about it, isn’t it, and that’s why live performance is utterly different from listening to a CD, because of that communion, the common experience.

And I don’t know how it is for the orchestra, but having totally attentive people standing from the start makes for a completely different dynamic.

The silence is just incredible when a hall of 6000 starts listening.

Any oaf can sing slowly and loudly, but you have to prove you can sing fast and loud

(Here Bettina Schimmer, Stenz's PR, remarks on "how amazing it was yesterday, because usually the Cologne audience can be quite noisy")

Cough, cough, cough. But yesterday, they were really quiet. Sure, it depends on the event. But what a great way of celebrating the Philharmonie, just the kind of occasion that I think is necessary for putting on Mahler 8. It should never be just part of the season,

The other thing is the pacing, which is so crucial. That moment we talked about might not have worked so well had you not prepared – I’ve heard performances where you lose interest half way through the second movement.

Then you have to reignite and it’s much nicer if it unfolds naturally.

But is the symphony one of the hardest in that respect?

I think the pitfalls are the kind of deepest you can come across in that journey. And I’ve heard performances just like the one you are describing where through ill pacing and the sonorities not adding up Mahler 8 just doesn’t reveal its beauty. I think it really is the perfect work of art, it really is a piece of utter beauty, profundity, a message and a sound world that takes you beyond words, And for all these components to happen in front of your eyes.. There are a few hurdles you have to take, I think, and I’d be thrilled if for you as a listener it had a natural pace and the sequence of events really needs to build in the right way.

And the climax of the first movement which is so long delayed, when the choirs hurtle back to the "Veni Creator" You know when it works and doesn’t.

That also takes some careful work, and you know one of the crucial things is apart from logistics such as whether you have the right amount of rehearsal time, with masses of people there is the tendency to follow the lowest common denominator and take a slow pulse, that keeps it together the whole time, but then you’ve achieved togetherness for no purpose whatsoever, and the crucial thing for the choirs is to trust that they can be virtuosos. That's the beauty of living in Cologne – I had the chance to get together with all the Cologne choirs in July, before the summer break, and to say OK, this is what I expect here, and we had a rather promising session but nowhere near the result you were able to hear last night, and I said to them, look, any oaf can sing slowly and loudly, but you have to prove you can sing fast and loud, then it becomes impressive if 400 people take off and sing like a rocket, and that in itself wouldn’t be impressive, but the score demands this impetus, doesn’t it. Allegro impetuoso, the stormy approach.

But not too much to start with. And all the choral writing in the middle, "Accende lumen sensibus", it's a killer. You know, a fantastic performance like last night makes me think new things about this symphony all the time, not least these incredible interrelationships between the movements.

Yes, those motifs, the way they change clothes...

And the timing of bringing back the big ideas of "Veni Creator Spiritus" in Part Two, the point at which he does it shows he's really a born opera composer.

Just recently I was asked about some of those aspects, and I was reminded that Mahler was at the height of his experience when he composed the symphony, and so you don’t conduct 250 or so opera nights a year – one of the singers tried to make a point, did Mahler really know what he was doing there, and I said, come on, he knows when a singer can sing a piano and how loud the orchestration can be. And he's so cruel with the soloists. Despite that, they worked as a team, I thought. Something you cannot know in advance, almost from an inner urge, the ensemble began to behave like an ensemble, they were impressed with the achievements of the choir, they were impressed with the way their roles were treated. The conductor always promises, my orchestra will accompany you, give me the colours, and then what very often happens is they do it for one rehearsal, before the orchestra plays out and all the colours are gone, I said, look every conductor will tell you that, but I tell you the Gürzenich Orchestra will accompany you, so give me the colours. And that takes an element of trust, but then we did have enough time in the Philharmonie on Thursday last week to actually deliver. To fulfil the promise.

Just recently I was asked about some of those aspects, and I was reminded that Mahler was at the height of his experience when he composed the symphony, and so you don’t conduct 250 or so opera nights a year – one of the singers tried to make a point, did Mahler really know what he was doing there, and I said, come on, he knows when a singer can sing a piano and how loud the orchestration can be. And he's so cruel with the soloists. Despite that, they worked as a team, I thought. Something you cannot know in advance, almost from an inner urge, the ensemble began to behave like an ensemble, they were impressed with the achievements of the choir, they were impressed with the way their roles were treated. The conductor always promises, my orchestra will accompany you, give me the colours, and then what very often happens is they do it for one rehearsal, before the orchestra plays out and all the colours are gone, I said, look every conductor will tell you that, but I tell you the Gürzenich Orchestra will accompany you, so give me the colours. And that takes an element of trust, but then we did have enough time in the Philharmonie on Thursday last week to actually deliver. To fulfil the promise.

I read in the programme that you were a student here when you first heard it, what was the impact then?

I was 21, that was 1986 -I remember the music just hitting me, It was Janowski conducting the performance with which the hall opened (pictured above right by Klaus Barisch), and therefore it was like a big bang on many levels: my first Mahler 8 live and being exposed to this incredible soundworld and also for Cologne the city, having a hall like this. Because the old 16th century Gürzenich Hall, handsome as it is, is nowhere near being an ideal concert hall. So for classical music world and the two international orchs in Cologne, this was the start of a new era.

And the fact that Mahler gave the world premiere of the Fifth Symphony here with the Gürzenich. That’s pretty important.

It is. A good chunk of the Gürzenich Orchestra had also played at the first performance of the Third Symphony in Krefeld, in a composite orchestra, so Mahler knew many of the Gürzenich musicians before he came here for the Fifth. The Philharmonie itself is a fascinating hall,. You know how we were talking about the focus and how to pull the audience to the music on stage, the amphitheatre shape does that very well.

Did it take its cue from the Berlin Philharmonie?

Up to a point, I’m speculating here, but if I’m an architect I see what the benchmarks are and see what’s inspiring and what’s not. But they did come up with something unique, I’ve never seen anything similar, in its roundness, in terms of the amphitheatre.

How would you describe the acoustic for you?

I think it’s luscious, it’s true to the performer, what you hear on stage is what you hear out there, sometimes you end up in venues where you have to bend the balances in the orchestra for things to work in the hall, which is always very unsatisfactory because you have to work against your instincts on stage, whereas here, you can work with your instincts and be sure that the hall will just enhance your efforts.

Plus you’ve got all those spatial resources for the brass bands.

A good Mahler performance takes off when every performer starts to give and play with his or her own personality

That in itself is exciting for me as a conductor, there are quite a few spatial pieces around and I always have a field day. For example we did a concert performance of Parsifal, because we’ve been going through renovations in the opera house, and the way we were able to layer the choirs and the offstage choirs was very special, or something like Quasi una fantasia, György Kurtág’s piece, where you want to surround the audience. It's a quintessential spatial hall.

George Crumb would be good.

Absolutely. I’ve got him on my short list. As for the "offstage brass" in Mahler 8, I've heard many performances where you only get them from the one position, because Mahler in this score only says "isolated placement". He doesn’t say from behind or left, or right. Now I knew I would like the first movement to end like a rocket, acceleration, acceleration, we have lift-off. Now if you then put the brass behind the audience, you get distance problems, and it doesn't work for anyone. Which is why we ended up with the brass bands on top balconies right and left, more or less still in front of the audience, so it can come together for the audience when they play on time. But then for the very end you need blocks of sound, so they were first all bang in the centre of the audience, the three trumpets and four trombones as a unit in the centre, and then the only thing you hear from the offstage brass is a unison, so I had them fan out. So from the chunky sounds in the centre of the stage they went to being in a complete circle, like the course of planets for the very last sounds, and thus you had a total unified space.

Your started , both on disc and live, started with the Fifth Symphony. was it a conscious decision then that you were going to do a whole Mahler cycle?

Absolutely, I felt the orchestra has such an affinity to Mahler’s music that we might be able to create something special, so we made a conscious decision in 2009 that we could actually produce a whole cycle for Oehms Classics. Then it was a question of how to pace it, because unlike a concert orchestra, the Gürzenich with its opera duties has a limited number of slots. It’s fairly different from a standard concert orchestra to play only 12 programmes in a season, for example. There are other opera orchestras that do even less, like the Staatskapelle München or Staatskapelle Berlin.

Did you aim for one Mahler symphony a season?

Well, last season we did the Second at the beginning and the First at the end. And the timing of the Mahler 5 with the Proms and the runup to the new season, we felt that since the piece was written for us, it should be the starting point. You know how our Proms programme was a replica of Mahler’s first performance? The very first performance of 1904 cried out for a centenary performance which we first did in 2004: the Fifth in the first half, in the second Schubert songs and Beethoven's Leonore No. 3 Overture. So Mahler 5 was the first choice, then the so-called Wunderhorn Symphonie - 4, 3, 2 and 1 at the end of last season. Now we work through the later symphonies: Philharmonie anniversary year was the obvious time to do 8. We've been in the studio for the Adagio of No. 10.

You don’t agree with the Deryck Cooke completion?

I’ve done it. I think it does justice to the piece, I think it worked in the concert, however for our Mahler cycle I thought we’d rather stay with what we have from Mahler. And then we’ll record 7, 6 and finish with 9.

7 should suit the way you work with this orchestra, because of its incredible finesse with the woodwind in particular. I love that symphony.

Ah, you’re my man, because so many people frown when you mention Mahler 7.

Ah, you’re my man, because so many people frown when you mention Mahler 7.

I don’t have a problem with the finale, and surely the way you work with lots of energy and forward movement should suit it.

That will be my project, I can already promise you. Because it struck me, why slow down a festival? The last movement is a festival of ideas, it begins with the timpani, it wants to generate more…It should be close to the feeling of Meistersinger, if anything you need to create something where the audience is gasping, because there’s yet another idea, and yet another, and it has to have that circus around it, and then it can be the most exuberant thing. But if you start to agonise over tempo relations, you're lost

Also there surely shouldn't be too much heaviness – it topples but it never quite falls over.

No of course it doesn’t, Mahler would always want to be profound even in his exuberance, but none the less, you have to go for the flow, and if you don’t go with the flow, you generate it. And then it makes a wonderful contrast to the night pieces that precede it, so in hindsight those things fall into place.

The fourth movement is a fascinating transition...

And the intimacy is important.

You’ll be careful with your mandolin there, I'm sure – I loved the way one of the mandolinists last night stood up to play.

We had six others apart from the official mandolin player – I bribed the viola players to take on the rest. I said I know you as a special orchestra, here’s a mission for you, you might declare it mission impossible, but have a go, and there is a spot, Mahler writes mehrfach besetzt, because he wants a tutti effect, he doesn’t want one, but that's what you usually get. What often happens is that just in order to be heard, at the most serene moment, you get this frantic tremolo from the last man standing. You want the mandolin colour blending with the pianissimo chorus, and in my view you should follow what Mahler writes. So before they knew it, the violas had six mandolins. I knew I had 14 violas, and the violas in those bars play only pizzicato, broken chords, so I said, have a go and they did.

This is a level of detail which is what makes your cycle unique. From the start was that important – do you research what Mahler did in terms of positioning, or is it just instinct?

It’s instinct for Mahler, for me with my lifechanging experiences with Mahler’s music, Mahler 2 to begin with then 8…

Where did you first hear Mahler 2?

It was first a radio broadcast that completely overwhelmed me. It was rather late for a classical musician, probably I had just started to study in Cologne, so late teens, and I just remember being exposed to the music and thinking, that’s the way music should sound, that’s what I want from music, and so I checked out the immediate possibility of hearing a live performance. I went to Berlin to hear a performance in the Waldbühne, Abbado and the European Union Youth Orchestra, which was just overwhelming. So one experience led to another, I felt this incredible pull towards Mahler’s music.

There is no composer, apart from Wagner in the theatre, who tests the orchestra so - is that fair to say?

However clear music is on paper it is only the second best layer of the original idea

I think it’s fair to say. Because that test is a test beyond the professional skill. A good Mahler performance takes off when every performer starts to give and play with his or her own personality. And that is independent of the need to structure a performance, to come up with a suggestion for interpretation, timing and all that. And that's why despite the fact that Mahler’s music is stunning, even a Mahler performance can go wrong, because it just doesn’t get to the final hurdle.

It never leaves the ground.

Right, it never takes off. And that’s why Mahler was so amazed by Richard Strauss's music, I think he was gobsmacked how it seemed completely conductor proof, performer proof, the music just always works, and Mahler is a fight for detail, this voice, that element. His generous hint to future performers, please change things in order to create the spirit of the music: that is so liberating as a conductor, and from a man who was so obsessed with detail, to say, tailor my music so that the spirit speaks.

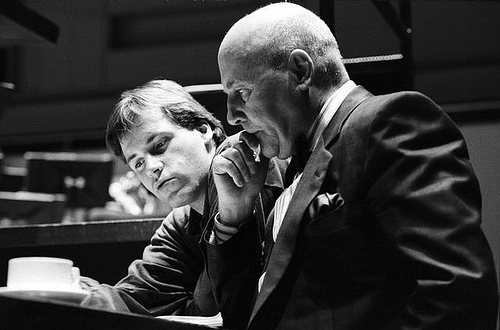

Did it make a difference coming from doing so much contemporary work in your early days with the London Sinfonietta, that aspect particularly say with the Seventh Symphony?

My theory there would be in many ways performing contemporary music was the most liberating experience because on a daily basis I was dealing with living composers (right, with Hans Werner Henze), people who have the task to translate their imagination to paper, and my task is to back-translate paper to idea. And seeing those composers at work I developed a feel for the difficulty of translating the idea to paper. In other words however clear music is on paper it is only the second best layer of the original idea, and recreating the original idea is very much in its own right the creative process.

My theory there would be in many ways performing contemporary music was the most liberating experience because on a daily basis I was dealing with living composers (right, with Hans Werner Henze), people who have the task to translate their imagination to paper, and my task is to back-translate paper to idea. And seeing those composers at work I developed a feel for the difficulty of translating the idea to paper. In other words however clear music is on paper it is only the second best layer of the original idea, and recreating the original idea is very much in its own right the creative process.

And you have composers on hand giving advice, or saying I’ll change that because it’s not working…

So just the idea that a score is not set in stone but only a blueprint for the original idea is a liberating experience. Being true to the score means being true to the original idea rather than being true to what’s in print. That aspect is probably the biggest harvest from my early years working a lot with contemporary composer. And then I took a different path, I left London, I started in Berlin and then I discovered the symphonic kernel with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, a top orchestra but not so much on the European radar, so I conducted my first Mahler, Brahms and Beethoven cycles there. I did some 125 programmes there, so when I returned to Cologne it was very much, I had my contemporary phase, my experimental phase, my phase when things can go wild, then I had my phase when I rediscovered the music of the more distant past.

When I returned to Cologne of course there was the cosmos of opera. Prior to that I had only done it here and there, not on a regular basis, and now with the Cologne opera being such a hub of international repertoire, I was able to further my experience of music, we did the whole Ring cycle, Tannhäuser, Tristan, Lohengrin.

It's the same with our London Philharmonic, which also plays at Glyndebourne: surely it's most rewarding for a symphony orchestra to get to play opera too.

I agree with you totally: an orchestra that also gets to play in an opera house pit will be the most fulfilled. I now have a much broader experience than I did during my time in London, and that broader experience is probably just as influential with me as it is with other conductors. There's no substitute for developing steadily with an orchestra. We had a little reception last night with our donors, and the orchestral committee was there too, and I said we couldn’t have done this in years one or two, we needed to build it up, we needed tours, exposure, Proms, recording projects not just with me but also with Kitaenko, we needed the tour to China where we played the first Ring cycle in Shanghai, and all that. It takes time, but I'm very happy with where we are now.

Watch the whole Cologne performance of the Eighth on YouTube

Markus Stenz's next concert in Manchester's Bridgewater Hall with the Hallé Orchestra is on 28 February 2013: Mozart Concert Arias with Valda Wilson and Mendelssohn's complete incidental music to A Midsummer Night's Dream

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Monteverdi Choir, ORR, Heras-Casado, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - flames of joy and sorrow

First-rate soloists, choir and orchestra unite in a blazing Mozart Requiem

Monteverdi Choir, ORR, Heras-Casado, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - flames of joy and sorrow

First-rate soloists, choir and orchestra unite in a blazing Mozart Requiem

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Classical CDs: Shrouds, silhouettes and superstition

Cello concertos, choral collections and a stunning tribute to a contemporary giant

Classical CDs: Shrouds, silhouettes and superstition

Cello concertos, choral collections and a stunning tribute to a contemporary giant

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

theartsdesk at the Lahti Sibelius Festival - early epics by the Finnish master in context

Finnish heroes meet their Austro-German counterparts in breathtaking interpretations

theartsdesk at the Lahti Sibelius Festival - early epics by the Finnish master in context

Finnish heroes meet their Austro-German counterparts in breathtaking interpretations

Classical CDs: Sleigh rides, pancakes and cigars

Two big boxes, plus new music for brass and a pair of clarinet concertos

Classical CDs: Sleigh rides, pancakes and cigars

Two big boxes, plus new music for brass and a pair of clarinet concertos

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

Add comment