Bizet: Carmen Suite No. 1, Symphony No. 1 in C, Gounod: Petite Symphonie Scottish Chamber Orchestra/François Leleux (Linn)

Bizet: Carmen Suite No. 1, Symphony No. 1 in C, Gounod: Petite Symphonie Scottish Chamber Orchestra/François Leleux (Linn)

Initial impressions are disconcerting, the bass thwacks at the start of the first suite extracted from Bizet’s Carmen by Ernest Giraud almost too polite, but the ears adjust quickly; what we get is what you’d hear in an orchestra pit. I’d forgotten how good this music is in its original form, having spent too much time recently marvelling at Rodion Shchedrin’s offbeat string transcription. François Leleux’s Scottish Chamber Orchestra are superb, flautist Silvia Careddu and oboist Robin Williams deserving shout-outs. You know that this CD will prove to be a winner just a few seconds into the little “Intermezzo”, Bizet’s melody passing neatly between solo winds. Leleux is unfussy but affectionate, giving the music enough space to breathe whilst revelling in the extrovert moments.

Bizet’s Symphony No. 1 was composed in 1855 when he was just 17 but waited 80 years for a first performance. Why Bizet buried the work and never referred to its existence is a mystery; it’s a superb work, and not just for a teenager. Beethoven’s influence is never far away, tempered with a generous dose of Rossini. This performance has irresistible bounce and joie de vivre, Leleux’s dashing tempo in the finale never an issue for the SCO strings. You’re repeatedly struck by how idiomatically Bizet wrote for wind instruments, and there’s an apt coupling in the shape of the Petite Symphonie, written by Bizet’s mentor Gounod for nine winds. One of many works commissioned by flautist Paul Taffanel, it’s a delight, and demonstrates just how good Parisian woodwind playing was in the 19th century. There’s a rumour that Gounod deliberately gave the second oboe very little to play, getting his own back on a musician he suspected of having an affair with his wife. Leleux plays principal oboe here but never hogs the limelight. A real feel-good disc, with sumptuous sound.

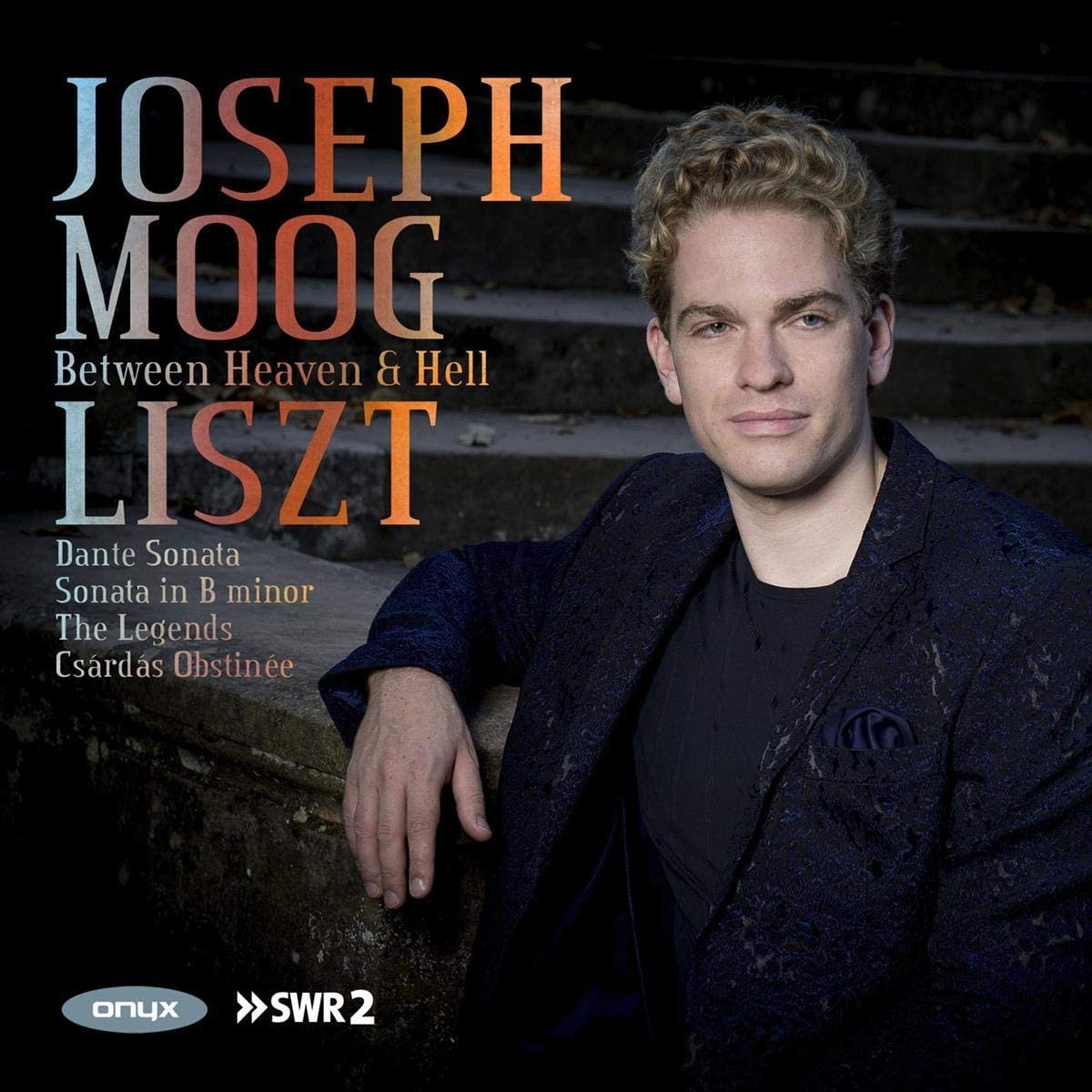

Liszt: Between Heaven and Hell Joseph Moog (piano) (Onyx)

Liszt: Between Heaven and Hell Joseph Moog (piano) (Onyx)

This disc’s schlocky title and gothic artwork are pretty apt for a disc encompassing Lisztian extremes, though Joseph Moog’s expression suggests that he’ll be a friendly guide. It’s true: this account of Liszt's Sonata in B minor is as witty as it is dramatic, Moog tackling the faster passages as if he’s accompanying a melodrama on the hoof. I can’t recall any recorded performance which has entertained me so much, Moog relishing the sonata’s emotional extremes. The ominous fff chords which interrupt the first section are genuinely scary, before a radiant take on the “Andante sostenuto”. I’m not convinced that Liszt was a great melodist; the things which stand out for me when listening to the sonata are the unexpected tempo and key changes, the structural boldness. Moog knits things together beautifully, this performance feeling much shorter than it actually is. The soft close is mesmeric, the bar lines seemingly disappearing. Piano technician Ulrich Charisius is rightly credited in the booklet, the Steinway’s lowest pedal notes wonderfully clear.

Not even Moog’s gifts can prevent Liszt’s noisy Dante Sonata from sprawling, but he’s flawless technically. More palatable are the Deux légendes, Liszt’s delightful depiction of St Francis of Assisi preaching to the birds anticipating Messiaen. As a brilliant encore we get the Csárdás obstinée, an exhilarating, baffling Hungarian dance packing a wealth of invention into barely three minutes.

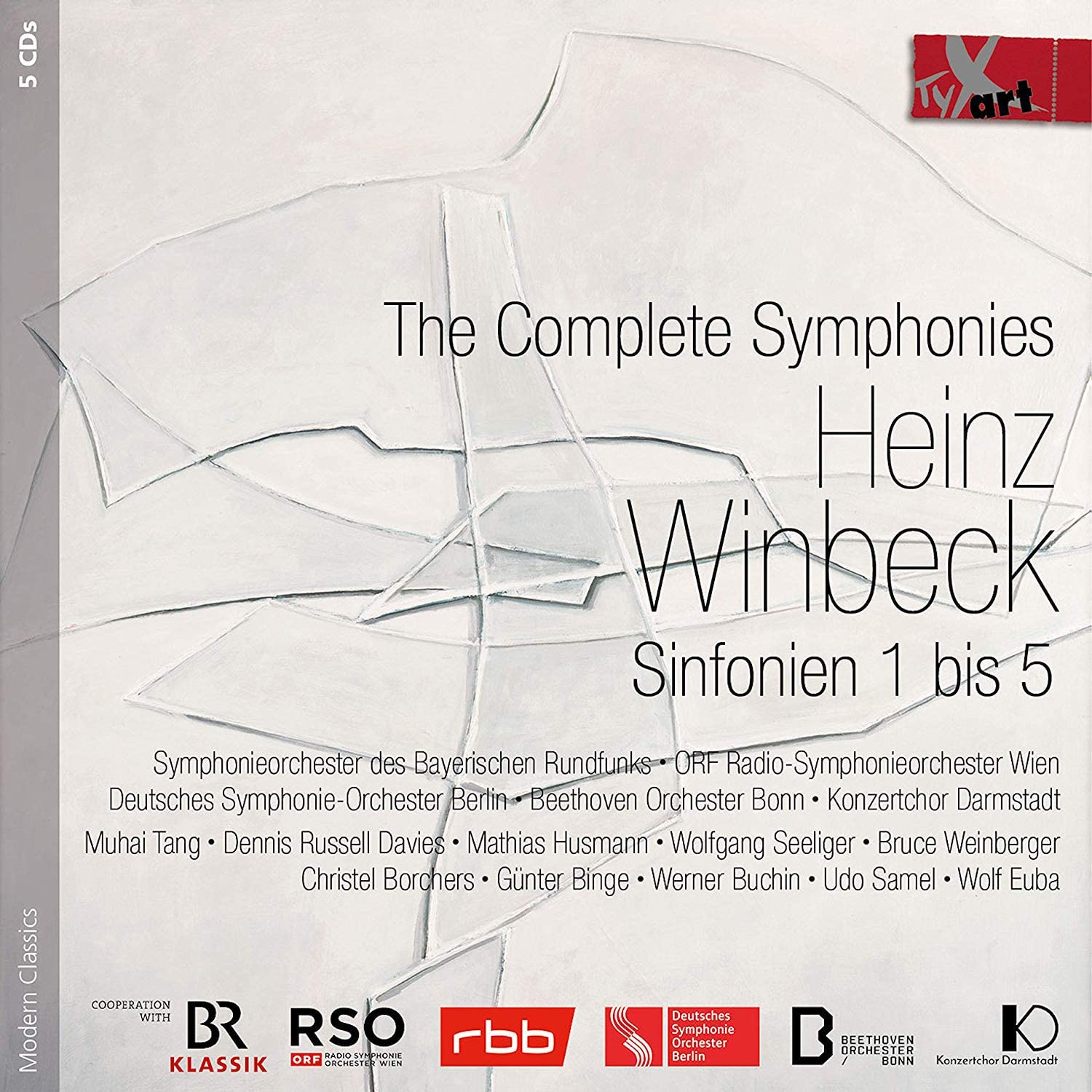

Heinz Winbeck: Symphonies 1-5 (Tyxart)

Heinz Winbeck: Symphonies 1-5 (Tyxart)

Good symphonies are still being written; conductor Kenneth Woods and his English Symphony Orchestra are part way through commissioning nine new ones, and several composed in the last century’s closing decades are, I think, masterpieces. Sample Lutosławski’s 3rd and 4th if you don’t believe me. And here’s a box of five contemporary symphonies, completed between 1984 and 2009 by the German composer Heinz Winbeck (1946-2019). Dark, uncompromising but readily accessible, they’re a real find. If you’re searching for a suggestion as to how these pieces sound, there’s an useful booklet contribution from conductor Dennis Russell Davies (“I can claim with some certainty to be the only conductor who has performed all five Winbeck symphonies…”), who recalls how his enthusiasm for Glass and Adams “was often considered a betrayal of my work with Berio”, and that a colleague suggested he investigate Winbeck, whose music offered “a path from a rich tradition leading to today’s modern sounds and forms”. Winbeck’s engagement with the music of the past is a constant: Bach, Berg, Mahler, Schumann and Wagner are alluded to, and his Symphony No. 5 is an eloquent response to Bruckner 9 and the best place to start listening, so let’s work backwards. Russell Davies had suggested to Winbeck in 2001 that he complete Bruckner’s unfinished finale, Winbeck instead producing a vast four-movement symphony, its subtitle translating as “Now and in the hour of Death”. Fragments of the finale’s chorale crop up along with other Brucknerian references, the symphony partly a moving attempt to reflect the older composer’s desperate struggle to finish the work. Bruckner would have ended his 9th in a blaze of D major; Winbeck opts for an uncertain, ethereal fade. It’s a remarkable piece, and this live recording from Russell Davies and the Deutsche Symphonie-Orchester Berlin carries a potent emotional charge.

Symphony No. 4 is more ambitious still, a large orchestra combined with pre-recorded tape, speaker, chamber choir and four vocal soloists. Inspired by the death of Winbeck’s mother, it sets words from the Latin Mass along with verse by the 20th century Ukrainian poet Georg Trakl. This is the hardest of the five symphonies to assimilate, the introspective mood frequently at odds with the vast forces deployed. Trakl’s words are also sung and recited in the dark Third Symphony, Mahler’s influence especially strong. It’s also there in the remarkable slow finale to No. 2, its tender string hymn eventually silenced by loud percussion. Symphony No. 1’s violent opening both scares and thrills, a spectacular tenor saxophone obbligato disrupting the final movement. This is an absorbing, important box set, and essential listening if you’re feeling adventurous. Four of the performances are live recordings, and the sound consistently impressive. No sung texts are provided but documentation is otherwise excellent. A winner.

Add comment