Classical CDs Weekly: Borup-Jørgensen, Mahler, Philippe Grisvard & Johannes Pramsohler | reviews, news & interviews

Classical CDs Weekly: Borup-Jørgensen, Mahler, Philippe Grisvard & Johannes Pramsohler

Classical CDs Weekly: Borup-Jørgensen, Mahler, Philippe Grisvard & Johannes Pramsohler

An amazing Danish musical seascape, moving Mahler, French baroque violin exhumations

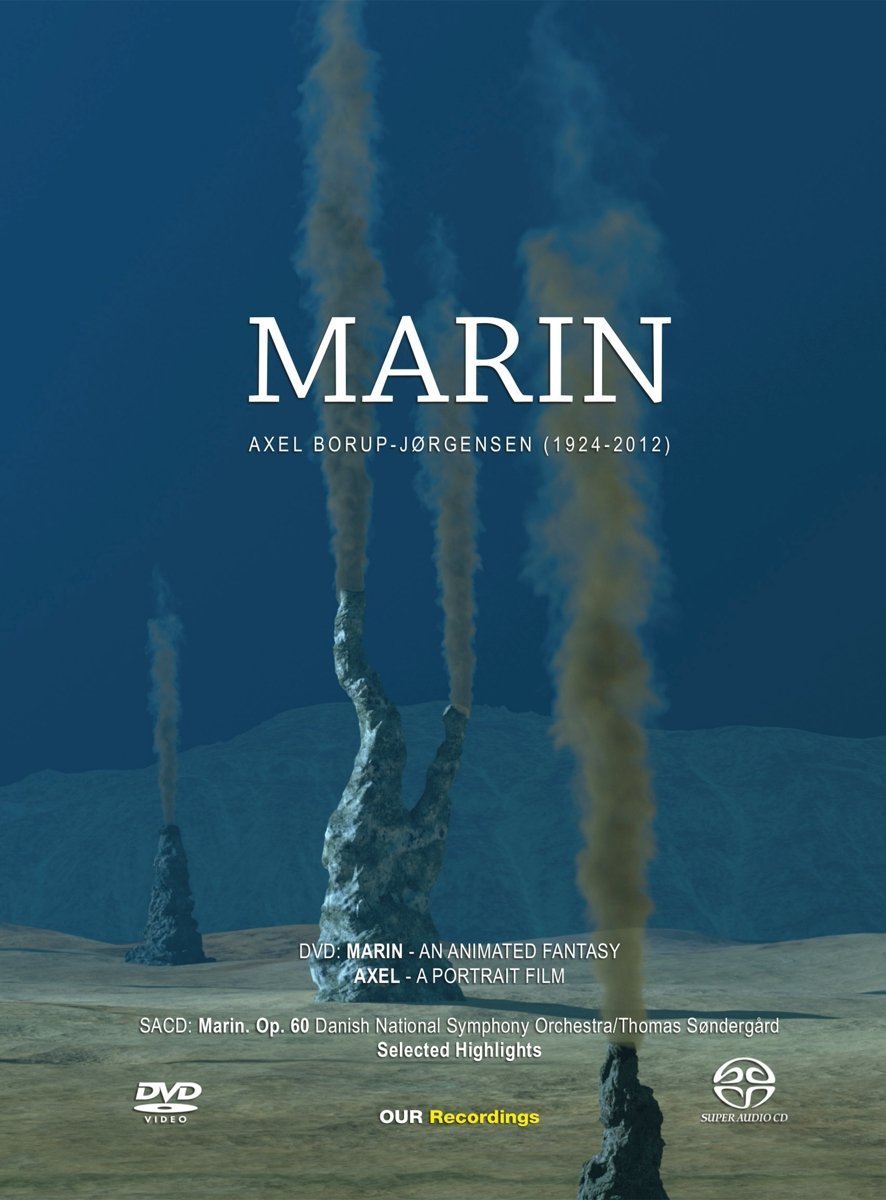

Axel Borup-Jørgensen: Marin Danish National Symphony Orchestra/Thomas Sôndergård (OUR Recordings)

Axel Borup-Jørgensen: Marin Danish National Symphony Orchestra/Thomas Sôndergård (OUR Recordings)

The physical effort involved in composing Marin was a huge strain on the Danish composer Axel Borup-Jørgensen (1924-2012). This ear-stretching musical seascape was made possible by its creator winning a prize in the mid-1960s, the reward including a commission for a large orchestral piece to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the Danish National Symphony Orchestra in 1970. Borup-Jørgensen delivered, in spades: a shaggy monsterpiece with the orchestral strings divided into 55 parts, using something referred to, mysteriously, as "optical notation". Making a fair copy took the composer over 1000 hours, the process entertainingly described by his daughter in the booklet. A young Herbert Blomstedt conducted the premiere, following a score with pages so enormous that an ingenious means of turning them soundlessly had to be devised. You couldn't make it up. Still, this handsomely recorded new performance of Marin with the same orchestra under Thomas Søndergård is a triumph. It sounds like nothing else you'll have heard, 19 minutes of deep rumblings, dissonant note clusters and pregnant silences. Importantly, it does really suggest a vast, swelling ocean. We’re not a million miles away from the stormier bits of Debussy’s La Mer or Sibelius's Oceanides. The recording comes with an accompanying DVD including Morten Bartholdy’s CGI animated realisation of Marin, an entertainingly crazed vision of an undersea world, its denizens based on the composer's own drawings. I listened to the work before watching the film and was anticipating something darker and murkier: the crystalline brightness of the artwork came as a surprise. Still good to have though, as is the bonus documentary about Borup-Jørgensen. Which suggests that he was a genuine talent, a likeable maverick with an acute ear, able to analyse a work by Webern using graphics rather than words. It's touching to see him recalled so fondly by fellow musicians.

Marin’s vastness seems to have been a blip, Borup-Jørgensen generally preferring to write on a smaller scale. The couplings are fascinating: 1989’s Für Cembalo und Orgel (with harpsichordist Mahan Esfahani) is bewilderingly brilliant, as are two pieces for solo recorder. The second of them, Pergolato, was the composer’s last work, an elegant, melodic farewell. The disc closes with Coast of Sirens, soprano Bodil Gümes’ multitracked vocals heard against a shimmering chamber backdrop. The whole package is handsomely designed and well-annotated: a treat, in other words. What's stopping you?

Mahler: Symphony No. 5 Gürzenich-Orchester Köln/François-Xavier Roth (Harmonia Mundi)

Mahler: Symphony No. 5 Gürzenich-Orchester Köln/François-Xavier Roth (Harmonia Mundi)

This is exceptionally good, a vivid, dramatic and deeply moving account of a symphony that's surprisingly difficult to get right on disc. Cologne’s Gürzenich-Orchester gave the first performance of Mahler's 5th in 1904, and they’ve already recorded a decent version under Markus Stenz. François-Xavier Roth's account is better still; his performance has a sharpness and clarity that’s dazzling. I can usually predict whether I’ll enjoy a reading of Mahler 5 by listening to the first tutti, 20 seconds after the solo trumpet fanfare. It's marvellous here, a widescreen blast of brassy noise. You can hear every note, and there's an even better chord seven minutes in, a technicoloured outburst which wouldn’t sound out of place in Messiaen. It's what Mahler wrote, though, and his scoring sounds unerringly modern at times. There's bite aplenty in the second movement and a very mellow, European-sounding solo horn in the vast scherzo.

For al the clarity Roth can summon up plenty of orchestral warmth when needed, understanding that this score looks back as well as forward. His “Adagietto” is ideally paced, a well-earned wallow before the perkiest of finales. The symphony's closing chorale whizzes past, sounding exuberant rather than impatient. I loved it. Mahler recordings nowadays tend to be live performances: this one was taped in the studio, so the playing is refreshingly fluff-free. Oddly, the notes aren't translated into English, but welcome this as a chance to practice your French or German.

French Sonatas for Harpsichord and Violin Philippe Grisvard (harpsichord), Johannes Pramsohler (violin) (Audax Records)

French Sonatas for Harpsichord and Violin Philippe Grisvard (harpsichord), Johannes Pramsohler (violin) (Audax Records)

More high quality exhumations from baroque violinist Johannes Pramsohler, whose many talents include sniffing out long-forgotten repertoire which genuinely does deserve to be reheard. Eleven compact sonatas spread over a pair of CDs may seem lot to take in, but he and harpsichordist Philippe Grisvard understand and nail the distinct character of each work. This is music history with lashings of entertainment thrown in. France in the early 17th century hosted a swathe of composers keen to assert the values of abstract, "absolute" music. Like the extravagantly named Jean-Joseph Cassanéa de Mondonville (“chamber music can perhaps offer today's audience more than just audacity…”), whose Sonata in G minor gleams, its fast-moving finale a real tonic. Most of these pieces are described as keyboard sonatas with violin accompaniment. Grisvard’s energy never flags, despite some punishing writing in three sonatas by Louis-Gabriel Guillemain. Pramsohler knows exactly when to step back and cede the limelight. Delicious moments abound, my favourite being the middle movement of Michael Corrette’s Sonata in E minor; Grisvard matched note for note by Pramsohler's avian chirpings.

The pair tap into the melancholy grandeur at the start of Luc Marchand’s A minor sonata, throwing in a compelling account of the closing “Carillon du Parnasse”. You wonder whether they take the middle movement “Larghetto” of Mondonville’s Sonata in A Major a tad too quickly, but their flowing pace works a treat, the lyricism never tipping over into sentiment. An outstanding collection, in other words, with erudite notes and handsome packaging.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

theartsdesk at the Lahti Sibelius Festival - early epics by the Finnish master in context

Finnish heroes meet their Austro-German counterparts in breathtaking interpretations

theartsdesk at the Lahti Sibelius Festival - early epics by the Finnish master in context

Finnish heroes meet their Austro-German counterparts in breathtaking interpretations

Classical CDs: Sleigh rides, pancakes and cigars

Two big boxes, plus new music for brass and a pair of clarinet concertos

Classical CDs: Sleigh rides, pancakes and cigars

Two big boxes, plus new music for brass and a pair of clarinet concertos

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

BBC Proms: Alexander’s Feast, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan review - rapturous Handel fills the space

Pure joy, with a touch of introspection, from a great ensemble and three superb soloists

BBC Proms: Alexander’s Feast, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan review - rapturous Handel fills the space

Pure joy, with a touch of introspection, from a great ensemble and three superb soloists

Add comment