For most people a turntable, or record player is used to play back old vinyls bought from a market or second hand store, or perhaps a carefully packaged reissue of a classic album. We gently place the needle at the beginning of the record and are careful not to scratch the vinyl when we turn it over. But for a turntablist or DJ it is a musical instrument, and they handle it with much greater confidence and familiarity. When two turntables are set up with a mixer a wealth of new musical worlds can be created.

This relatively new musical tradition of turntablism has a fascinating and rich history which is only about 40 years old. To my mind it’s one of the most unique and interesting instruments to emerge in recent years. Though the turntable has had occasional appearances in classical music, starting with John Cage’s seminal Imaginary Landscape No.1 in 1939, its more recent emergence through hip-hop culture as a very expressive rhythmic instrument, with the emergence of professional “turntablists” as true virtuosos, has only just started to be explored in classical music.

The incredible skill and musicality of these turntablist performers was what primarily drew me to compose a Concerto for Turntables. Having witnessed the frequently jaw-dropping dexterity of DJ routines at local DJ battles in Birmingham when I was a student, and listening to the super-creative cutting up and fluid manipulation of obscure samples by people like DJ Premier & Jazzy Jeff, I was aware that this was an extremely developed musical tradition. So why not put this magical new instrument as a soloist in front of a classical symphony orchestra?

A central feature of the classical concerto has always been to showcase the skills and musicality of the best soloist of the time, and often explore newly emerging instruments; whether it’s Mozart composing a concerto for the recently developed clarinet, inspired by the virtuosity of Anton Stadler, or Tchaikovsky’s now ubiquitous Violin Concerto, which was so virtuosic that at first it was considered unplayable. I was keen to show that this new instrument, that had evolved out of hip-hop-culture in 1970s New York, could stand on its own as a serious classical soloist.  From a music history perspective, there are actually many interesting parallels found in the evolution of the turntables compared to classical instruments. For example, as the mechanism of the piano evolved in the 19th century, virtuosity became more and more of a focus. Piano duels became popular events, as made famous in story of Beethoven and Steibelt. Then pianists and composers such a Chopin and then Liszt pushed the boundaries of the newly improved, steel-framed piano to the limit, inventing new pianistic techniques to astound their audiences. Over the last 40 years turntables has gone through a similar evolution; firstly the importance of battling and virtuosity. From the early days, “DJ battles” were a focal point of the culture, and a platform for DJs to show off their latest techniques(a quick search shows how various pioneering DJs have continued to invent new techniques over the decades). Those informal battles have since evolved into the annual DMC Championships which have become the focal events for turntablists and showcase ever increasing levels of virtuosity.

From a music history perspective, there are actually many interesting parallels found in the evolution of the turntables compared to classical instruments. For example, as the mechanism of the piano evolved in the 19th century, virtuosity became more and more of a focus. Piano duels became popular events, as made famous in story of Beethoven and Steibelt. Then pianists and composers such a Chopin and then Liszt pushed the boundaries of the newly improved, steel-framed piano to the limit, inventing new pianistic techniques to astound their audiences. Over the last 40 years turntables has gone through a similar evolution; firstly the importance of battling and virtuosity. From the early days, “DJ battles” were a focal point of the culture, and a platform for DJs to show off their latest techniques(a quick search shows how various pioneering DJs have continued to invent new techniques over the decades). Those informal battles have since evolved into the annual DMC Championships which have become the focal events for turntablists and showcase ever increasing levels of virtuosity.

Secondly, the technology of the instrument itself has been evolving too. The original set-up of two Technics SL-1210s and a mixer remain as the Steinway (or perhaps the Bechstein) of the turntables world, but the mixers now have in-built effects and filters, and turntables now have greatly increased pitch control and stability. But most interestingly for composers is the emergence of “Vinyl Emulation Software”, which allows a turntablist to use a special vinyl with corresponding software, to control any sound they like, without having to engrave it on the vinyl itself. This 15 year old technology allows the turntables immediate control over any sound you can load into the software, so makes it much more flexible as an expressive controller of sound, and it is no longer limited by the vinyl records available. In composing my Concerto for Turntables this new technology meant that we could continually fine tune the sound of the samples used by the turntablist, and even record sounds live from the orchestra straight to the turntables.

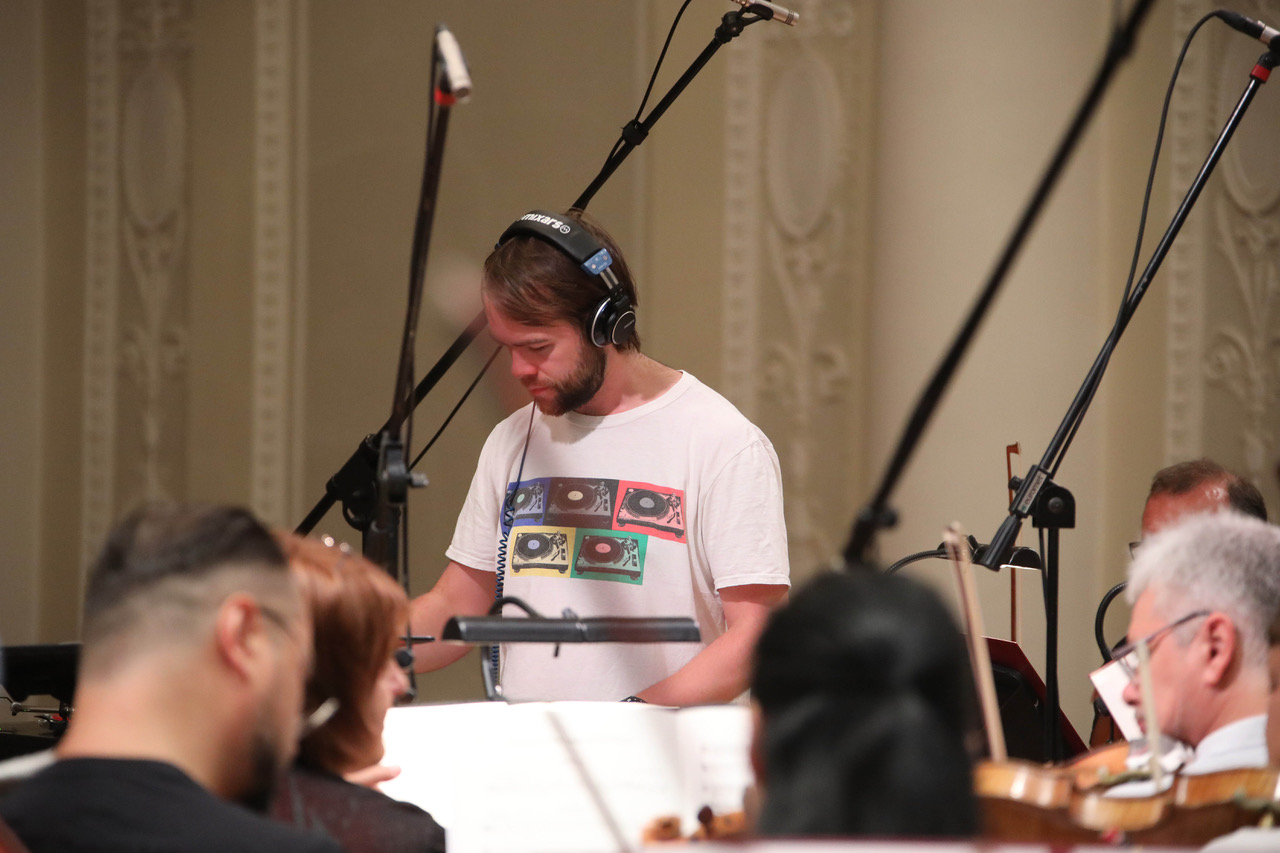

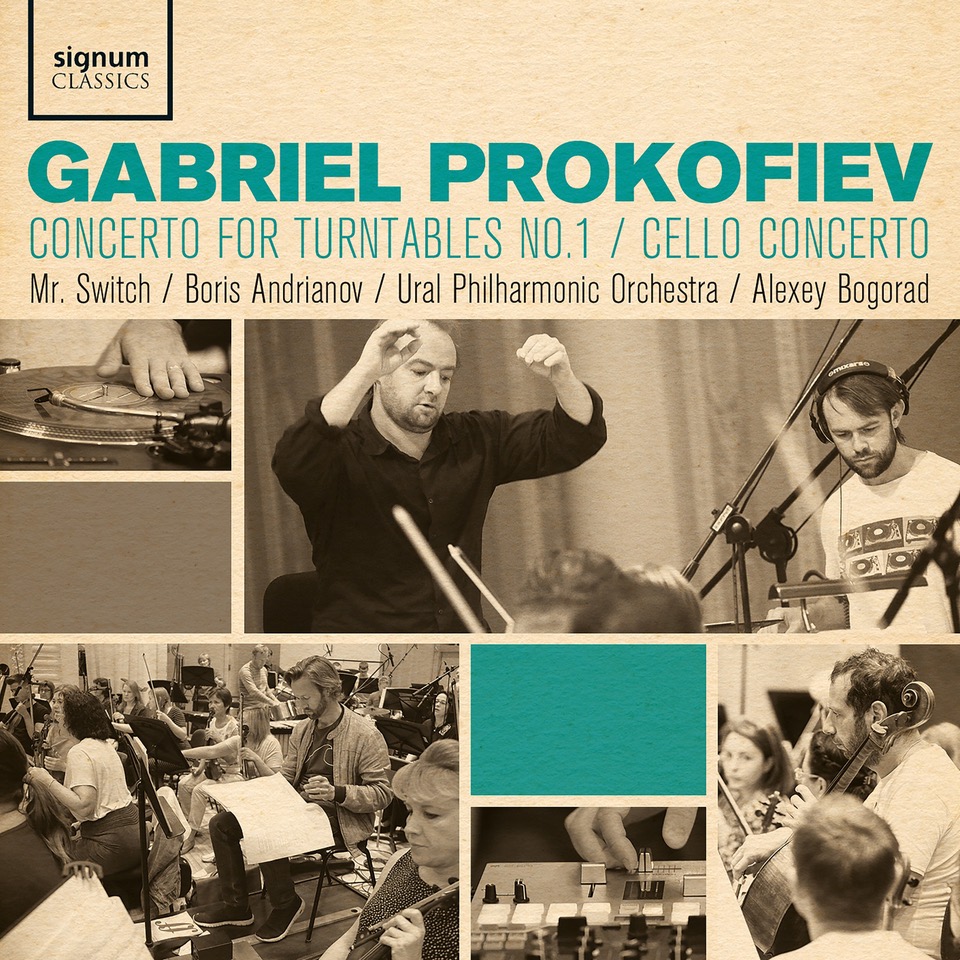

This historically familiar evolution of the turntable further convinced me that it is one of the most significant new instruments of the early 21st century. Turntables are generally written off by people who haven’t properly experienced a performance by highly trained turntablist and don’t realise the wealth of techniques and possibilities beyond the clichéd “waka-waka” scratching parodied in mainstream culture. [Pictured below: Mr. Switch at the Yekaterinburg recording] It’s true that when I was approached by pianist and producer Will Dutta to compose the Concerto for Turntables, my first concern was that it would come across as a gimmicky youth-orientated project. Also combining an instrument from a different musical culture with an orchestra is a big challenge, and it’s hard to name a really successful concerto for a non-classical instrument, so I was right to be cautious. But the wonderful thing about the turntables is that they don’t have any sounds of their own, and so by choosing the right sounds for the vinyl the composer or turntablist can connect and combine with other instruments with great fluidity. It’s surprising then, that turntablism and scratching has been dominated by just a small handful of popular samples (the most popular being the “Ahhh” sample from “Change the Beat”), which contain frequencies that work really well for rhythmic scratching.

It’s true that when I was approached by pianist and producer Will Dutta to compose the Concerto for Turntables, my first concern was that it would come across as a gimmicky youth-orientated project. Also combining an instrument from a different musical culture with an orchestra is a big challenge, and it’s hard to name a really successful concerto for a non-classical instrument, so I was right to be cautious. But the wonderful thing about the turntables is that they don’t have any sounds of their own, and so by choosing the right sounds for the vinyl the composer or turntablist can connect and combine with other instruments with great fluidity. It’s surprising then, that turntablism and scratching has been dominated by just a small handful of popular samples (the most popular being the “Ahhh” sample from “Change the Beat”), which contain frequencies that work really well for rhythmic scratching.

So in composing a classical Concerto for Turntables, the choice of sounds was incredibly important, I needed sounds that would allow the turntablist to express virtuosity, but also sounds that would musically work with the orchestra. My solution was to give the turntables the sounds of the orchestra that it was playing with, so that the turntables would have a selection of specific phrases or single sounds from the orchestral performance, and would then manipulate them into a solo part that would interact with the orchestra.

To properly compose for turntables, you really need to get inside the instrument and learn about all its possibilities, as is the case for composing for any instrument. I discovered that every different gesture and pattern had a different name and required slightly different movements of the vinyl and the cross-fader; a musical system that reminded me of the different ornaments found in baroque music (another parallel in the evolution of a new musical culture).

A clip of the 2011 National Youth Orchestra performance conducted by Vladimir Jurowski

The turntablist techniques - the baby, transform, chirp, crab, flare, scribble and so on - are known by all turntablists, and as I was composing one of the first ever concertos for turntables I felt that it was important that I included most of these techniques and celebrated these main aspects of this relatively young instrument. I could have used the turntables more as a sophisticated sound generator as composers such as Shiva Feshareki are really successfully doing, but I really wanted to show the Turntables as a virtuoso solo instrument.

So I decided that each movement of the concerto would focus on particular aspects of turntablism. The introduction movement is a simple but bold introduction to the turntables showing the simple “baby” technique and the “transform” with gong and double bass samples, then the second movement starts with a string motif, but played back by the turntables, not the orchestra. Then turntables and strings playing the same 11 beat phrases simultaneously but slipping in and out of phase with each other, prompting the audience to question our perception of what is live and what is pre-recorded.

For the third movement, I had come up with a slowed-down hip-hop inspired “groove” for the orchestra, and so I wanted that movement to showcase all the classic scratch ornaments that clearly referenced the hip-hop roots of turntablism. DJ Yoda, for whom I originally composed the work, insisted that he needed a vocal sample in order to do classic scratch solos. But I had set myself the rule of only giving the turntables sounds created by the orchestra, so I added a little bit of theatre to the score which instructs the musicians to start chatting, and then have one yawn loudly, another exhale loudly after sipping on a fizzy drink, and finally have the conductor cough in order to silence the chatter. These three different vocal sounds all work really nicely as scratch sounds, and also clearly show the audience how any sound from the orchestra can then become musical sounds for the turntablist, even if they are just a cough. This moment also brings in humour to the piece and so broadens the emotional contrasts in the Concerto which I think is very important in such a piece. [Pictured below: Gabriel Prokofiev with Yekaterinburg conductor Alexey Bogorad].  For the slower fourth movement, it was important to show the more sensitive side of the turntables, and so in I focused on a lesser known melodic aspect of the instrument. As well as being able to change the speed of the turntable between 33rpm and 45rpm, all DJ decks have a pitch control for more precise speed changes. Using the +8, -8 and 0 settings of the Technics 1210 gives us a kind of six-note minor mode, which I used to create a haunting melodic part for the soloist using a sample of a long flute tone. The turntablist uses the fader on the mixer to add dynamics and phrasing, and can even add extra vibrato with pitch control. The fifth movement builds to a battle between the percussion section and the turntablist, who explores “drumming” techniques of turntablism.

For the slower fourth movement, it was important to show the more sensitive side of the turntables, and so in I focused on a lesser known melodic aspect of the instrument. As well as being able to change the speed of the turntable between 33rpm and 45rpm, all DJ decks have a pitch control for more precise speed changes. Using the +8, -8 and 0 settings of the Technics 1210 gives us a kind of six-note minor mode, which I used to create a haunting melodic part for the soloist using a sample of a long flute tone. The turntablist uses the fader on the mixer to add dynamics and phrasing, and can even add extra vibrato with pitch control. The fifth movement builds to a battle between the percussion section and the turntablist, who explores “drumming” techniques of turntablism.

Finally, in most classical concertos, soloists are given a cadenza, an unaccompanied solo in which they can show-off their own unique virtuosic skills. Because the turntables are traditionally a solo instrument, and the culture has a focus on “battle routines”, which are in themselves a kind of cadenza, I decided to give the turntablist a cadenza in every movement, to explore the deeper possibilities of each sets of sounds. These cadenzas were first developed between myself and DJ Yoda, and then regularly discussed with Mr. Switch who has found more and more interesting ways of working with the sound-sets for each cadenza, and the cadenzas have almost become a set of miniature explorations of manipulating orchestral music in their own right.

Composing the Concerto, I realised just how rich the possibilities are for this instrument in a classical composition, and my first concerto was just the beginning of my journey with the instrument. Depending on what sounds are given to the turntables, whether recorded instrumental or found sounds through to pure electronics, the range is immense. Could it be the longed-for expressive controller of recorded and electronic sounds that has been missing from live electronics?  In 2013 I was asked to composed a second Concerto for Turntables, and at first I resisted; I didn’t want to become that “turntables’ composer”. But knowing I had only just started to explore the instrument with the first concerto, and remembering the enjoyment I had composing for it, meant my resistance didn’t last long, and in 2014 I wrote a Triple Concerto for Trumpet, Percussion & Turntables. This concerto focused on conversations between the turntablist and the other soloist, focusing on the turntable as a musical magpie which “steals” phrases from the percussion and trumpet and then re-plays/transforms them.

In 2013 I was asked to composed a second Concerto for Turntables, and at first I resisted; I didn’t want to become that “turntables’ composer”. But knowing I had only just started to explore the instrument with the first concerto, and remembering the enjoyment I had composing for it, meant my resistance didn’t last long, and in 2014 I wrote a Triple Concerto for Trumpet, Percussion & Turntables. This concerto focused on conversations between the turntablist and the other soloist, focusing on the turntable as a musical magpie which “steals” phrases from the percussion and trumpet and then re-plays/transforms them.

Then in 2016 I composed a Second Concerto for Turntables (for Sinfonica de Casa da Musica, Porto, in Portugal, conducted by Baldur Brönnimann, pictured below). My starting point was to focus on the sonic characteristics of the turntables that can augment the sound of the orchestra. Sub-bass and high-frequency clicks, reversing textures, became important elements of the turntable part. But I stuck to my approach of giving the turntables sounds that were recorded from the orchestra, and for the opening created a theatrical trick: the turntables start by play-backing the sound of the orchestra tuning up, then gradually slow down that “concert A” until it becomes a throbbing sub-bass sound. There is one other technique that I explored for the first time: “Needle Percussion”, which doesn’t use the vinyl at all, but instead has the turntablist tapping the needle against the central spindle and the edge of the platter (interestingly it was John Cage, again, who first experimented with the needle as the instrument in his 1960 piece Cartridge Music).

I’ve yet to use electronic or found-sounds on the turntables, and so there are still more sound worlds to explore.  A big issue that a composer writing for turntables has to deal with is of course notation. In composing a concerto, I needed to notate the turntables part not just for the soloist but for the conductor as well. Back in 2006 there was one established method of turntable notation: TTM (Turntablist Transcription Methodology), an impressively accurate grid-based, proportional, graphic notation. However, I felt that it would be tricky to incorporate TTM into an orchestral score (which is not proportionally spaced), and that conductors wouldn’t want the extra work of learning a new notation system. So I notated the turntables like a percussion instrument, with added instructions, indicating which sound and which technique should be used. For the melodic writing, standard notation was essential, and I marked the pitch control settings above the note. This method seemed to be the fastest way for a DJ or conductor to grasp what the Turntables should be doing.

A big issue that a composer writing for turntables has to deal with is of course notation. In composing a concerto, I needed to notate the turntables part not just for the soloist but for the conductor as well. Back in 2006 there was one established method of turntable notation: TTM (Turntablist Transcription Methodology), an impressively accurate grid-based, proportional, graphic notation. However, I felt that it would be tricky to incorporate TTM into an orchestral score (which is not proportionally spaced), and that conductors wouldn’t want the extra work of learning a new notation system. So I notated the turntables like a percussion instrument, with added instructions, indicating which sound and which technique should be used. For the melodic writing, standard notation was essential, and I marked the pitch control settings above the note. This method seemed to be the fastest way for a DJ or conductor to grasp what the Turntables should be doing.

I also marked many passages ritmo ad lib. as another important feature of my concerto was to give the turntablist the freedom to improvise the finer details of the rhythms and ornaments. Not only was this a nod to the emphasis on improvisation found in baroque concertos, but also to allow turntablists their own characterful interpretation of the piece, and not have their style cramped by struggling to read the music precisely. I’ve been really excited by the different character each of the many soloists who have performed the concerto has brought to the piece, and I am looking forward to seeing how other composers and soloists continue the journey of this unique instrument.

Add comment