It’s Beethoven all right, but not as you know him. The scowl is there, and the broad heroic shoulders too, but the iconic tousled hair is glowing a rather unexpected shade of orange. A purple cloak sweeps down to the floor, setting off a jaunty pair of Elton John-style glasses and a leopard-print waistcoat.

Wherever you go in Bonn during the 2012 Beethovenfest lifesize models of the city’s favourite son greet you, brooding out from inside shop windows, or posing casually (as casually as a bright green hulk-inspired mannequin can) on a street corner. Photos from previous years reveal a waxwork Beethoven in a t-shirt printed with the legend “Who the fuck is Mick Jagger?” Ludwig van B was the original rock star, and it’s not something Bonn is going to let us forget. It’s a typically irreverent gesture from the city that takes its culture seriously, but not itself.

Although the first festival was held in 1845 to mark the 75th anniversary of the composer’s birth, a rather chequered history has only recently seen it develop from a sporadic, more haphazard affair into an annual month-long celebration with some 70 events in its core programme. The repertoire too has diversified dramatically to include not only contemporary classical works but also jazz, folk and even this year a rap performance.

Although the first festival was held in 1845 to mark the 75th anniversary of the composer’s birth, a rather chequered history has only recently seen it develop from a sporadic, more haphazard affair into an annual month-long celebration with some 70 events in its core programme. The repertoire too has diversified dramatically to include not only contemporary classical works but also jazz, folk and even this year a rap performance.

Situated only 20 miles from Cologne, for 11 months of the year Bonn lives musically in the shadow of this cultural hub, which boasts the Philharmonie concert hall (Bonn’s own Beethovenhalle is overdue an update, though plans are underway for a new festival hall situated next to the Rhine) as well as a highly-reputed opera house and orchestra. But during September roles are reversed. Major international soloists and ensembles join the civil servants and students who make up the bulk of the city’s population, with this year’s lineup including Pierre-Laurent Aimard, the Borodin Quartet, András Schiff, and the Bayerishes Staatsorchester, among others.

For many however the 2012 festival highlight was surely the extraordinary opportunity of seeing Paul Hindemith’s early triptych of expressionist operas – Mörder, Hoffnung der Frauen/Sancta Susanna/Das Nusch-Nuschi (the latter pictured above) in a fully-staged production at the Bonn Opera. These early experiments see the composer in his first stages of rebellion, stretching and straining dramatic and structural principles to reflect the political upheavals of the 1920s – interrogating the brutality of so-called civilisation within its own tonal terms, rather than through the outright rejection of Schoenberg.

It’s an exercise whose formal control (Sancta Susanna, pictured left, is an opera in Sonata Form) belies the passionate expressiveness of the music, inhabiting familiar harmonic landscapes but distorting their vistas just as Hindemith’s expressionist contemporaries in the visual arts were doing. The results are a confronting fusion of parody and symphonic richness, experimenting with the richly-coloured textures that would later make Mathis der Maler such a success. Based on Oskar Kokoschka’s provocative dramas that deal frankly in sex, religion and social taboos, Hindemith’s triptych found nothing like the same acceptance however. An early Hamburg production made its audience sign a contract promising not to disrupt the performance, while as late as 1977 a staging in Rome caused the opera house’s director to be fired.

It’s an exercise whose formal control (Sancta Susanna, pictured left, is an opera in Sonata Form) belies the passionate expressiveness of the music, inhabiting familiar harmonic landscapes but distorting their vistas just as Hindemith’s expressionist contemporaries in the visual arts were doing. The results are a confronting fusion of parody and symphonic richness, experimenting with the richly-coloured textures that would later make Mathis der Maler such a success. Based on Oskar Kokoschka’s provocative dramas that deal frankly in sex, religion and social taboos, Hindemith’s triptych found nothing like the same acceptance however. An early Hamburg production made its audience sign a contract promising not to disrupt the performance, while as late as 1977 a staging in Rome caused the opera house’s director to be fired.

While it seems unlikely the heads will roll as a result of his new production, director Klaus Weise’s didn’t shy away from confrontation. The bafflingly-titled Mörder, Hoffnung der Frauen (Murder, Hope of Women) saw Die Frau (Julia Kamenik, pictured right) stripped to the waist and attacked with a chainsaw before taking part in a group orgy, while the Orientalist fantasy-parody of Das Nusch-Nuschi with its cast of eunuchs, over-sexed warriors, courtesans and castration-themed plot didn’t so much flirt as go all the way with Vegas-style vulgarity.

While it seems unlikely the heads will roll as a result of his new production, director Klaus Weise’s didn’t shy away from confrontation. The bafflingly-titled Mörder, Hoffnung der Frauen (Murder, Hope of Women) saw Die Frau (Julia Kamenik, pictured right) stripped to the waist and attacked with a chainsaw before taking part in a group orgy, while the Orientalist fantasy-parody of Das Nusch-Nuschi with its cast of eunuchs, over-sexed warriors, courtesans and castration-themed plot didn’t so much flirt as go all the way with Vegas-style vulgarity.

Curiously though it was Sancta Susanna, the most restrained visually, whose tale of a nun’s sexual awakening shocked the most, trusting to the collision between the erotic insistence of Hindemith’s score and the sober traditionalism of its religious setting to work their friction.

Musically things were a little uneven. Hindemith’s scores are as generous and sprawling as Kokoschka’s dramas are unyielding, and Bonn’s Beethovenorchester under Stefan Blunier didn’t always achieve the necessary depth. Offstage effects worked well, with brass assaults for Mörder’s war of the sexes and frankly pornographic flute writhings for Sancta Susanna, but the strings failed to match the shifting sound-worlds of each piece, retaining the same rather undercooked colouring throughout.

Kamenik’s Die Frau was a stand-out, and this powerful young soprano returned for a seductive turn as First Dancer in Das Nusch-Nuschi. The pairing of Ingeborg Greiner’s Satanic Susanna and Anjara Bartz’s repressed Klementia gave unexpected psychological credibility to this concise tragedy, and the quartet of Mung Tha Bya’s wives in Das Nusch-Nuschi (Kathrin Leidig, Vardeni Davidian, Charlotte Quadt and Greiner again) managed to carry Hindemith’s slight lapse into indulgence, but with the exception of Roman Sadnik’s mischievous Tum Tum the men proved weak, with Mörder’s soloists particularly unequal to their female rivals.

Bonn has something of a personal stake in German expressionism. The city’s Kunstmuseum, which rears its angular head up into the decorous landscape of Bonn’s “museum mile”, is home to a large collection of paintings by August Macke – a leading member of Der Blaue Reiter group of artists, and a long-time inhabitant of the city. You can visit his house-museum, but the Kunstmuseum has the bigger (and better) permanent collection of works, including some almost Hockney-esque landscapes, electric with colour and movement (trees cast orange shade, houses have purple roofs) and some primitive nudes. An early self-portrait sees the artist stare quizzically out: a grave, moustachioed youth (pictured above left) with a mathematically precise side-parting elsewhere on show. A further collection of expressionist paintings by Franz Jansen and Alexej von Jawlensky is amplified by a small group of Max Ernst sculptures in bronze – sinister, alien figures, their cartoonish familiarity distorted by grotesque features.

Bonn has something of a personal stake in German expressionism. The city’s Kunstmuseum, which rears its angular head up into the decorous landscape of Bonn’s “museum mile”, is home to a large collection of paintings by August Macke – a leading member of Der Blaue Reiter group of artists, and a long-time inhabitant of the city. You can visit his house-museum, but the Kunstmuseum has the bigger (and better) permanent collection of works, including some almost Hockney-esque landscapes, electric with colour and movement (trees cast orange shade, houses have purple roofs) and some primitive nudes. An early self-portrait sees the artist stare quizzically out: a grave, moustachioed youth (pictured above left) with a mathematically precise side-parting elsewhere on show. A further collection of expressionist paintings by Franz Jansen and Alexej von Jawlensky is amplified by a small group of Max Ernst sculptures in bronze – sinister, alien figures, their cartoonish familiarity distorted by grotesque features.

But while Bonn’s post-war institutions and architecture champion a progressive, determinedly contemporary agenda, it’s also a city with a foot in the past. The Romanesque Minster dominates the central square, while the Marketplatz is crowned by the gilded pastel prettiness of the Old Town Hall. The Beethovenfest doesn’t neglect this traditionalism, and it is perhaps most keenly reflected in the festival’s three-year concert cycle of Beethoven string quartets performed by the Borodin Quartet.

Embodying an approach to performance that belongs to another era, the Borodins (pictured right) are a group that shun displays of showmanship in favour of a serious interiority. It’s a philosophy whose scholarly merit can occasionally translate to stiffness, but in the core Russian and German repertoire that the ensemble have inhabited for almost 70 years often sees them as unequalled in authority. Their final concert of this season paired Beethoven’s early Quartet No. 5 in A major with the late Razumovsky Quartet No. 2, with Borodin’s impassioned Quartet in D major as a centrepiece. With the filmy First Violin part catching the acoustic of the St Hildegard Mehlem Church, this opening quartet glittered with Mozartian brilliance. Violist Igor Naidin has the light sound of an English tenor, and set the tone for the lyric delicacy of this rendition. Only Ruben Aharonian’s occasionally rather tight virtuosics marred the ease of delivery, with the denser fugal passages of the central Allegro also jangling slightly in this resonant space.

Embodying an approach to performance that belongs to another era, the Borodins (pictured right) are a group that shun displays of showmanship in favour of a serious interiority. It’s a philosophy whose scholarly merit can occasionally translate to stiffness, but in the core Russian and German repertoire that the ensemble have inhabited for almost 70 years often sees them as unequalled in authority. Their final concert of this season paired Beethoven’s early Quartet No. 5 in A major with the late Razumovsky Quartet No. 2, with Borodin’s impassioned Quartet in D major as a centrepiece. With the filmy First Violin part catching the acoustic of the St Hildegard Mehlem Church, this opening quartet glittered with Mozartian brilliance. Violist Igor Naidin has the light sound of an English tenor, and set the tone for the lyric delicacy of this rendition. Only Ruben Aharonian’s occasionally rather tight virtuosics marred the ease of delivery, with the denser fugal passages of the central Allegro also jangling slightly in this resonant space.

Rather unexpectedly the Razumovsky emerged with absolute clarity, generating an altogether darker tone from the quartet that kept one eye always on Beethoven’s distant thematic clouds. If the closing Presto felt a little too dignified, it carried a dramatic weight that made sense within their reading of the earlier movements. Always stately, it was lovely to hear the quartet release into something more passionate for the Borodin, with cellist Vladimir Balshin taking an almost operatic lead.

Traditionalism collided with the present-day in a concert by Paavo Järvi and the Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen – the festival’s orchestra in residence since 2004. Regular appearances in Bonn have built up a strong relationship between this ensemble and the local audience, and the collective energy in a packed Beethovenhalle was palpable. It was as nothing however compared to the power pulsing off the stage in Brahms’ Symphony No. 2.

Jaarvi (pictured left) plays a long game with his material, prioritising a holistic vision of each movement, whose long arcs deliver huge climactic payoffs. As two encores demonstrated, the Kammerphilharmonie are an orchestra that know what to do with dynamics, but despite their broad range these escape affectation or the gratuitousness of a Barenboim because Jaarvi insists that they earn each one. Here, in the Allegro non troppo, Jaarvi wasn’t afraid to expose the symphony’s frayed emotional edges, setting up a narrative that only found resolution (and what resolution!) in the closing bars of the Allegro con spirito.

Jaarvi (pictured left) plays a long game with his material, prioritising a holistic vision of each movement, whose long arcs deliver huge climactic payoffs. As two encores demonstrated, the Kammerphilharmonie are an orchestra that know what to do with dynamics, but despite their broad range these escape affectation or the gratuitousness of a Barenboim because Jaarvi insists that they earn each one. Here, in the Allegro non troppo, Jaarvi wasn’t afraid to expose the symphony’s frayed emotional edges, setting up a narrative that only found resolution (and what resolution!) in the closing bars of the Allegro con spirito.

An elegant performance of Stravinsky’s neoclassical Monumentum pro Gesualdo di Venosa by the Kammerphilharmonie’s strings introduced the theme of musical dialogue through history, also explored in fellow Estonian Erkki-Sven Tüür’s Questions… This is a work long on concept and sadly short on character. Combining the Hilliard Ensemble (who had earlier performed a sequence of Machaut motets) with the orchestra, the works sets up the dialogue of an alternatim psalm between the instrumental and vocal groups. This textural opposition is intended to draw significance and contrast from the work’s text – a Q&A with quantum physicist David Bohm. The English prose of this exchange is as clunky as it sounds, not lending itself to any but the most anti-expressive treatment. Comparing Tüür’s textures to those of Arvo Pärt (as the programme notes attempted) does him no favours, leaving his cluster-chords and American minimalist cycles of activity looking raw by comparison to the ascetic ecstasy of his countryman.

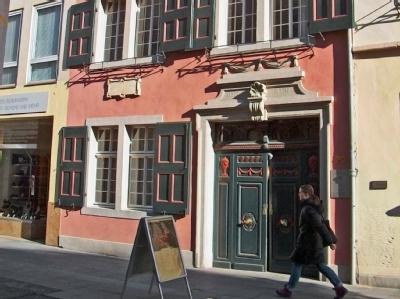

No trip to Bonn would be complete without a visit to the Beethoven House – the composer's small courtyard home (pictured right) on the Bonngasse, just behind the Market Square. The museum now housed here has expanded into the adjoining properties, and the comparison between their loftier apartments and the attic bedroom where Beethoven was born says much of the composer’s precarious existence, eventually working to support his family when his alcoholic father was unable to.

No trip to Bonn would be complete without a visit to the Beethoven House – the composer's small courtyard home (pictured right) on the Bonngasse, just behind the Market Square. The museum now housed here has expanded into the adjoining properties, and the comparison between their loftier apartments and the attic bedroom where Beethoven was born says much of the composer’s precarious existence, eventually working to support his family when his alcoholic father was unable to.

It’s a small museum, but worth visiting if only to see the collection of ear-trumpets (increasingly monstrous and implausibly large in size) that were made for the composer as his hearing worsened. A facsimile of the Heiligenstadt Testament (the original is in the museum archives) lies next to them, its frustrated fury raging passionately through the glass case. The museum doubles up as concert venue throughout the year, and the chamber-music hall offers period keyboard instruments on which Schiff performed Beethoven Sonatas during this year’s festival.

It’s a small museum, but worth visiting if only to see the collection of ear-trumpets (increasingly monstrous and implausibly large in size) that were made for the composer as his hearing worsened. A facsimile of the Heiligenstadt Testament (the original is in the museum archives) lies next to them, its frustrated fury raging passionately through the glass case. The museum doubles up as concert venue throughout the year, and the chamber-music hall offers period keyboard instruments on which Schiff performed Beethoven Sonatas during this year’s festival.

It says a lot about the Bonn Beethovenfest and artistic director Ilona Schmiel that its budget has actually risen since the start of the economic crisis. It’s a mark of good faith on the part of the city administration, whose early uncertainty about the festival has since crystallized into focused support for the event that provides such a crucial part of Bonn’s identity. The many decorated Beethoven statues may disappear from display after the festival ends, but the bronze monument to the composer in the Münsterplatz (built in large part thanks to the efforts of Robert Schumann) remains as a perennial reminder of his presence and his position at the centre of Bonn’s historical and contemporary cultural life.

Add comment