When I entered the light and spacious chief conductor’s room in Bamberg’s Konzerthalle, Jonathan Nott was poised with a coloured pencil over one of the toughest of 20th century scores, Varèse’s Arcana. He thought he might have bitten off rather a lot to chew the day after that night’s Bamberg programme of Jörg Widmann’s Violin Concerto, Strauss’s Eine Alpensinfonie and a new commission as part of the orchestra’s new Encore! project, David Philip Hefti’s con moto.

An Amsterdam Concertgebouw special beckoned, a large-scale throwback to Nott’s days at the head of the Asko Ensemble and the Ensemble Intercontemporain: as well as the Varèse, it included a recent work by a Dutch composer, Ligeti’s Requiem, the Kyrie from an Ockeghem Mass and – what was the Stravinsky piece for chorus and orchestra? Zvezdolikiy, The Star-Faced One, I suggested? “Don’t know, it’s there on the pile, haven’t looked at it yet” (it was). All this, and the week before Lachenmann’s Piano Concerto following Strauss’s Four Last Songs in Berlin, where the Bambergers had quite stolen the critical thunder from the Berlin Phil.

London has rarely had a look-in, and many readers may not know a name which stands alongside Rattle’s, Mark Wigglesworth’s and Robin Ticciati’s as the best of British; since starting out as repetiteur at the Frankfurt Opera in 1988, Nott has never crossed the channel for long, moving on to Wiesbaden, Lucerne, Amsterdam, Paris and now this town which is possibly the best to live in of them all. Working on standard symphonic repertoire alongside the new, and opera too – including Wagner's Ring over eight years which finally travelled to the Lucerne Festival last year, Nott has brought a fine orchestra to sit proudly among the best. The final releases in a Mahler cycle came out earlier this year, and since I’d five-starred the Sixth in a BBC Music Magazine review, that seemed like a good place to start.

London has rarely had a look-in, and many readers may not know a name which stands alongside Rattle’s, Mark Wigglesworth’s and Robin Ticciati’s as the best of British; since starting out as repetiteur at the Frankfurt Opera in 1988, Nott has never crossed the channel for long, moving on to Wiesbaden, Lucerne, Amsterdam, Paris and now this town which is possibly the best to live in of them all. Working on standard symphonic repertoire alongside the new, and opera too – including Wagner's Ring over eight years which finally travelled to the Lucerne Festival last year, Nott has brought a fine orchestra to sit proudly among the best. The final releases in a Mahler cycle came out earlier this year, and since I’d five-starred the Sixth in a BBC Music Magazine review, that seemed like a good place to start.

DAVID NICE: You’ve now come to the end of the big Mahler project. I guess you’re proud of that, and what a great way to finish, with the Sixth.

JONATHAN NOTT: Well, there’s quite an interesting story behind that. I fought tooth and nail over it, because that was done quite a long time ago, we’ve got a different stage set-up now, and the acoustic has changed. I’ve always wanted to do something with the original podium, which was a pentagon. That made a very big distance between the front and the first risers where we have the winds. We had Toyota come to try and improve it. I mean, a piece like tonight’s Alpensinfonie is just a bit too big for this hall, and I can’t always do anything about it. And the strings make a lovely sound in the hall, but the sound goes sideways and develops whereas the wind comes straight at you and it always feels as if they’re much too loud for the strings. After various improvements, I said we should do the Sixth again, and we fought about it and agreed about it and then disagreed, so in the end the old one did come out.

It would have cost a lot more since Bavarian Radio broadcast the concerts, which is how you’re able to bring out an expensive series like this.

Yes, and what’s particularly nice about that performance is that when I listened to the takes I said, "well look, this doesn’t sound right at all", and they spent a lot of time over it. They took all the data out and remixed it, which is great.

And you supervised that?

I sent copious lists of what I didn’t like. I supervised the Third Symphony, I went down to Munich. That was quite difficult to do because that really was only live, OK we had three concerts, and if it doesn’t sound the same in each concert, so I said, I’ve got to do this with you. They’d say, "that bit isn’t quite together", and I said, "I like the fact that it’s not together." The point is it’s such a big journey. I’d conducted the First before and the Fifth, I’d never heard the Seventh or the Ninth before we started either, so it was learning by experience.

Were they in the orchestra’s rep?

No. I mean, I’m sure they’d done One and Five before. But as the years went on we got more daring and decided to do things like these original bowing markings, which at the beginning seemed impossble and terribly uncomfortable. But after a bit you think, hang on, it’s completely different music if you do this. So bit by bit we erased those nice two-bows-a-bar things.

The detail is phenomenal.

It was very nice to do that. It’s always a bit tricky, isn’t it – I felt that especially about the Ninth – you want to have the detail, you see I can only get through these pieces if I colour them in the score, I want these colours to come out, on the other hand you want it to be as exciting a live performance as you can get. With the Ninth, we had a week’s worth of recording sessions, but in the middle of it was a live concert. The danger of that work is that if there’s no audience you disappear down the plughole, you get completely overwhelmed by this stuff and things are different to if you’re just throwing caution to the wind. That was what was great about the Ninth, I said, "look the [very quiet] end’s got coughs, but it has so much more to say than it did without an audience," and the end of the Third goes a bit crazy, but I said, "look, go for it" (below: at home in Bamberg, photograph by Peter Eberts).

It’s an interesting point, isn’t it, whether the feeling of electricity in a quiet audience can transfer to a recording – it would have to transfer to the playing otherwise on the recording you wouldn’t feel it. But it’s something of which one is so aware.

You’re very aware in performance – in a lot of these symphonies, the last few pages, you’ve done it when you’ve been fighting over an hour, and that makes a big difference as to what state you’re in by the time you get there. And to recreate that in a recording studio is difficult – but then you don’t want all the messes and the things that you don’t care about in a live performance but you certainly do if you’re listening back, and you think, "what the hell was that?" Recording detail is difficult. And of course these pieces have been recorded one zillion times before.

That’s what makes it so impressive – I mean, all the Mahler symphonies are a kind of benchmark for an orchestral standard, there’s no further you can go in many ways.

I agree.

Both your cycle and Markus Stenz’s –

I heard one of Markus’s, I was very impressed. I know Markus quite well.

I went to the Eighth in Cologne and the spatial effects with the brass groups were fabulous.

That’s a very good space for that piece.

So I’m very interested to hear the Alpensinfonie in this space. Is it on the cusp of being too big for the hall?

Yesterday [in the first of the two performances] there was a moment when the hall suddenly went [makes a sound midway between crunching and sucking in], I just want to be a little more relaxed today than yesterday. It’s very difficult because where I am, of course the brass is loud, but so are the strings, they’re very, very full next to me and it’s fine, but I go out in the hall and it’s not like that at all. How loud Is the organ, you know, it’s difficult to get that bang-on right.

It’s a conductor’s duty to go out in the hall and listen, isn’t it?

Yes, but there’s a difference between when it’s full and empty. Let’s see. It could do with being a bit taller, this hall, but you really feel as if you’re with the audience, and the audience feels it’s with the players, so it’s nice from that point of view.

Which I suppose is a German democratic model since Scharoun’s Berlin Philharmonie was built.

We were there last week, and it’s interesting. Because first of all it’s just a fantastically good hall. From the conductor’s podium you’re quite low in comparison to where everybody else is and you get the feeling you’re bang in the centre, which is the design intention. Normally, though, you’re up high with the audience around. You spend all your life not really knowing whether what you’ve done has come across, and you’re terribly reliant on the hall and you can get the impression – as with Disney Hall, it was almost too good, you can hear a pin drop over there. But what the hell. And of course the recording technique has changed so much. I was adamant with the Mahler cycle that we did it in surround sound because that was the latest technology and I was convinced more people would have this in their homes.

But it’s not really caught on, has it?

But it’s not really caught on, has it?

Not really. There are some things like Mahler Two, I made sure the trumpets were in four corners of the room so you really should get them coming round. But it’s difficult because actually what you want is a 7.1 system, because if you push the strings apart then suddenly they flip to the back channels, whereas it’s better if you have side ones, which I do have, but they’re not recorded like that. I thought it would be nice for the listener to get what it’s like for me, being surrounded by this sound. But it’s not easy to do. We did the Seventh with just two stereo microphones in the Vienna Concert Hall. And that has an amazing amount of power because you feel slightly squashed, actually, because it’s being squeezed through a tube of toothpaste, and I think, "wow, that’s great." With the surround, you have to play loud. I did that with the Second, I played ours and the Los Angeles one, because you get a completely different sound idea, it’s so brilliant, hits you in the face, and I thought ours was a little bit pale in comparison. But then you turn it up and you’ve got three times as much sound information. You’ve got this huge great richness of a thing, I personally go for a darker rather than a brighter sound, if you get it right then you’ve got that gut-wrenching feeling and I think it’s much more powerful and has more to say. But if you don’t have it that loud, and people don’t want to do that with headphones or in your own room with the neighbours knocking on the wall... So I think there’s a certain danger about the latest technology (above: Nott pictured by Thomas Müller).

And this fanaticism about detail, the recording engineers want to get exactly the same thing, and I say, "look, where’s my nice rich string sound here, I can hear all that, but what about the Karajan 1960s sound, that’s where the real sound of the orchestra resides?" Perhaps in the brass, and how the woodwinds play, but it’s the string sound which really dictates what kind of orchestra you’re listening to. So it was an experiment from all sides. But it’s been a very fascinating journey, and as things gradually went on, instead of being asked to do Brahms in Japan we were asked to do Mahler, and had a chance to do these works live in different venues. And the risk-taking. That’s something else characteristic about this orchestra, that they really want to play. Not this relaxed and come-to-us-if-you-would-like-to sort of thing. These Mahler symphonies give them the chance to do that. And getting to know each other better – it’s been over 15 years now, that’s a long time. I notice very much that as long as one keeps trying to self re-define, you end up with the possibilities of potentially amazing communication which must, if it’s done well, communicate itself to the audience.

So that you get to know the solo wind, say, so well, that you can trust them…

Exactly, you say, well, off you go, do your stuff, and if someone does something crazy or interesting, everyone else says "right". Because you’re giving the gesture and you’re never quite sure what response you’re going to get until you’ve had the response. Then it’s "oh that was exactly what I wanted" or "that’s not quite what I was expecting but alright"… I’ve never been one to rehearse something into the ground so that you simply produce it in the concert – I can’t do that.

I imagine the Seventh was especially interesting – there’s no more exposed symphony for every principal.

imagine the Seventh was especially interesting – there’s no more exposed symphony for every principal.

That was the last one we did in the end, and it was an enormous personal journey for them, for me too, because there’s never been another composer with whom I’ve spent so much time and read so much around, because it doesn’t seem to me to be at all clear what these things really mean.

You mean the emotional significance?

Exactly, what am I to say, given that the philosophical element is terribly complex…

He can be saying three things at once.

Usually, yes, and that’s quite difficult to do, I can easily juggle with two elements, but more is hard – and in the Seventh especially it’s not at all clear what you’re supposed to do.

That second Nachtmusik, I find it absolutely fascinating, it’s a serenade and transitional.

Oh, there’s an interesting story with that. I went through a huge great personal crisis around that time, and I remember wandering around with that serenade going through my head. I’ve got these JH audio headphones which mean I can walk down Sixth or Seventh Avenues and I can still listen to the quietest things. They’re moulded to the ear and once I’m in there in I’m cut off…it’s dangerous of course, and that’s one other thing which has been a problem or a blessing, the Wagners and Brahms and Schuberts and Bruckners, they pile it on and you can get really seriously lost as a listener. Then I find sitting still without music going on, that never really happens, actually, I get a bit nervous, and then what is this music really doing. In the Mahler case, I was wandering along on this bright sunny day, and I suddenly found this Nachtmusik was so C majory that it was painfully sad. And this saying goodbye to so many things, or the sadness of just being born and existence never quite… feeling homesick for somewhere that I knew I’d been as a being, and I might see it again, but I missed it. I always feel that Strauss wasn’t quite open enough about the second or third level of what he’s trying to say.

But when he does it’s extraordinary.

And if you let that in then the Alpensinfonie all becomes about the Epilogue, as a kind of allegory of what you’re going to do in life, and he’s just too good at these waterfalls and these clever cascades of orchestration, which you don’t get in Mahler because he’s very clear about ripping his guts out in front of your eyes.

This is me imposing an idea, but I have a very strong feeling about the end of the Alpensinfonie, that he wrote it in the middle of the First World War, and that the final theme is the theme of the climbers.

Oh definitely [sings it].

And it dies.

It dies.

Like Don Quixote. And it’s like all these young mountaineers – maybe this is overprogrammatic in my thinking –

Oh I don’t think so at all, I think it’s entirely –

That they’ve been wiped out, that’s it.

It’s only recently that I realized, yes, it’s First World War-ry stuff, in that time, but I was absolutely sure that the B minor cluster in the piece has existed before anybody else has existed and we have to, all of us, face some kind of mountains, and to be really human we have to climb them. But eventually it’s dust to dust, there is clearly no God here. But nature – I don’t know how many listeners will hear that theme at the end, but once you see it – you think, oh God, we’ve tried to be so poetic in this last bit and we’re going to be on the one hand destroyed and on the other we’re going back to nature. I totally agree with you that the piece becomes terribly touching and poignant – and others too. And even Heldenleben, OK, he’s quoting his own themes, but it can’t really be all about him, can it? And once you say, "let’s forget this, go on to that" – back to the Mahler serenade, I had a very strong feeling that I was being so C majorly positively charmed that I found it really upsetting.

It slips into the shadows all the time…

All the time. Then of course in Mahler Seven, if it says do the second subject a tiny bit slower than the first, it does not mean do it four times as slow, which makes the last movement completely different if that doesn’t work. The Eighth, how many hours did I spend looking at this theme here and then again an hour apart, how am I going to get to roughly the same sort of speed so the last movement works…I was personally proud, whether or not it comes across on the recording, that the second half of Mahler Eight, the pacing of it, did what I was hoping to do, that we would suddenly find ourselves in these keys without quite knowing how we got there, doing what it basically said, but it’s not entirely clear what it says…

It’s like a Wagner act, that second movement, isn’t it, like Siegfried?

Absolutely, and that’s something else we’ve had here, this Ring which we took to Lucerne, which all fits in. I did it first 17 years before that in Wiesbaden, then we did them one by one, but over eight years. I spent a long time trying to work out what was going on, which I knew really, but when you analyse where these things come from, and how they get changed, how lovely it is that in Siegfried’s second act when he’s singing about fear, we get Brünnhilde’s theme, so we know where that’s going to come from, but the way he creeps it around so that it morphs into something, I’m wondering whether I can make that clear over time. But you certainly can in Mahler and Strauss, and it’s being that balance between something that’s intellectually stimulating and something that’s emotionally challenging or freeing. I can’t have one without the other, I don’t like gushy gush for gush’s sake, it’s got to be clear in the gush, and on the other side like in contemporary music, I don’t want sterile nice white stuff that doesn’t say anything, it’s a complete waste of time.

But you have to get through the technical side of it before it can start to say something.

Yes, that’s why this Widmann concerto tonight is quite tricky. I mean, I know him quite well but it’s sort of dangerously gushy and to try and find some structure for something that’s over 25 minutes long, lovely sounds, lovely colours, but it’s difficult to follow that kind of thought process. Lovely sonority is great, we don’t always get that do we, but on the other hand it’s dangerously noodly, and there’s a lot going on in a space of beats, but on the other hand you’ve got to find these arches, which I suppose is what any Beethoven or Brahms symphony is asking you to do, but it’s more difficult in contemporary music when things are moving fast, and I’m not always totally sure that the composers themselves have thought about this. I find it very much the case in Lachenmann (pictured above by Astrid Ackermann on the right with Pierre-Laurent Aimard before Nott's recent performance of Lachenmann's Piano Concerto), he’s thought about that very cleverly.

Yes, that’s why this Widmann concerto tonight is quite tricky. I mean, I know him quite well but it’s sort of dangerously gushy and to try and find some structure for something that’s over 25 minutes long, lovely sounds, lovely colours, but it’s difficult to follow that kind of thought process. Lovely sonority is great, we don’t always get that do we, but on the other hand it’s dangerously noodly, and there’s a lot going on in a space of beats, but on the other hand you’ve got to find these arches, which I suppose is what any Beethoven or Brahms symphony is asking you to do, but it’s more difficult in contemporary music when things are moving fast, and I’m not always totally sure that the composers themselves have thought about this. I find it very much the case in Lachenmann (pictured above by Astrid Ackermann on the right with Pierre-Laurent Aimard before Nott's recent performance of Lachenmann's Piano Concerto), he’s thought about that very cleverly.

As a listener too you feel the timing even if you don’t always understand that, and you can’t analyse that if it’s not an obviously developmental thing.

No, that’s good, isn’t it, and on the one hand you’re up against people saying, "I want to enjoy contemporary music but I don’t understand it," and I keep trying to say, "look, there is nothing to understand about contemporary music, it’s just about experience, are you experiencing it and open enough to it?" You have to understand Beethoven, anything tonal, and if you don’t get that in Beethoven Seven’s first movement there’s a tritone here with no harmony, and you don’t notice it’s there, you’ve missed a huge chunk of what it’s about. You don’t really have to worry about the form in Lachenmann, but you do have to experience it. As a performer, I’m not very good at noodling on. I think that’s perhaps something that...

It’s thinking of the audience – it’s communication. If the audience is bored, something’s gone wrong.

It’s exactly that, isn’t it – if they cough, I’ve lost someone. But sometimes it’s because they’re frightened, and it is challenging. In the last 15 years, I must have been running around like an idiot most of the time, but the idea of being able to sit completely still for 15 or 20 minutes is such a joy. But how many people can sit still for 15 minutes? You see them in the audience, it doesn’t matter what it is, they won’t sit still, and if you’re not at one with yourself as a living human being, then it is very difficult to sit still, because you’re bombarded at quite a high rate of new experience in contemporary music. But it’s very rewarding and there’s a lot of beauty in there.

Next page: early training in opera and contemporary music, more on Strauss and the Bamberg sound

Above, Nott conducting the Gustav Mahler Jugendorchester at the 2009 Proms in Ligeti's Atmosphères

Recording-wise at least you first made your name with the contemporary repertoire and then when you came here there was more concentration on the classical-romantic repertoire, can I say that?

Yes, I was thinking the other day about Pierre-Laurent Aimard, who’s just a few years older than me but has had very similar life-history. I started my career conducting opera in Frankfurt. I wanted to be a singer, trained at the London Opera Studio but it didn’t work, I could play the piano, so I went in 1988 to Frankfurt and thought, great, I’ve got a job here. Within a year I got a chance to conduct, and then to conduct something big, because I said to [Gary] Bertini [then Frankfurt's chief conductor], I need to conduct, this is a big, big house and I understand very much if it’s not possible here, but then I have to find somewhere smaller. He gave me a chance, which was great.

Was it from there to Lucerne?

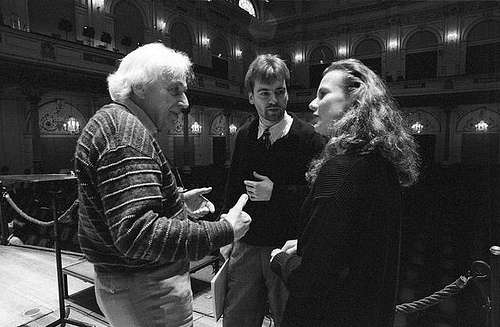

To Wiesbaden. I spent my first 15 years conducting all opera, that became less. I just went to Bari at the beginning of this year and did Elektra, which was my first time with a stage production for a long time. It was at Frankfurt that I did one of Heinz Holliger’s operas, and that coincided with meeting Ligeti with the Asko Ensemble in Amsterdam (the two pictured right in 1995 with Sybille Ehlert). It was an interesting technical challenge, and I said "why not?" I think it was lucky to have Ligeti at the start, he’s very simply clever, cleverly simple, and he always has something to say. As an interpreter you’ve got something to do. That element started up much more and the ensemble in Frankfurt and then the Ensemble Intercontemporain in Paris put the opera, the Bohèmes, alongside the Berio. But then people who met me in one life had no idea about the other life. Then I went to Lucerne with operas and concerts, and this came along in 2000 and that was concurrent, so at one time I was chief in Lucerne, here and chief of the Ensemble Intercontemporain, and that nearly killed me. Here in Bamberg there's always been that balance. We were always sure that we would bring out the Schubert and the contemporary simultaneously. And I liked the way that our latest encore piece echoes the Strauss.

To Wiesbaden. I spent my first 15 years conducting all opera, that became less. I just went to Bari at the beginning of this year and did Elektra, which was my first time with a stage production for a long time. It was at Frankfurt that I did one of Heinz Holliger’s operas, and that coincided with meeting Ligeti with the Asko Ensemble in Amsterdam (the two pictured right in 1995 with Sybille Ehlert). It was an interesting technical challenge, and I said "why not?" I think it was lucky to have Ligeti at the start, he’s very simply clever, cleverly simple, and he always has something to say. As an interpreter you’ve got something to do. That element started up much more and the ensemble in Frankfurt and then the Ensemble Intercontemporain in Paris put the opera, the Bohèmes, alongside the Berio. But then people who met me in one life had no idea about the other life. Then I went to Lucerne with operas and concerts, and this came along in 2000 and that was concurrent, so at one time I was chief in Lucerne, here and chief of the Ensemble Intercontemporain, and that nearly killed me. Here in Bamberg there's always been that balance. We were always sure that we would bring out the Schubert and the contemporary simultaneously. And I liked the way that our latest encore piece echoes the Strauss.

At one stage I got a bit fed up with Strauss, the way that in Rosenkavalier he’d be messing around with keys, and I never knew where I was, it seemed to be random, so I got a bit pissed off with him, but the Oboe Concerto is such a lovely piece of music, and the songs, that’s fair enough. But it was only more recently that I got to being touched by it at a much deeper level than I was expecting, and I began to wonder, is that who he really is, and was struck by the fact that he didn’t want that to be quite as open as Mahler, that you need to strip off a couple of outer garments.

From which works in particular?

The ones I’ve done more recently. Elektra is a case apart, it’s so impressive, but it was doing once again Heldenleben and Metamorphosen. I’d got this picture of Metamorphosen, how is it possible that the whole world has ripped itself apart and all someone like this can do is sit there and write this slightly gooey, gluey stuff? But really playing it at the piano and working out where it’s going harmonically, and finding that each time as we did it in concert or even rehearsals, like the end of Winterreise, it always had the power to make me think, there is great tragedy being expressed here, and wonderful positive moods. It was always clear that you’d never have a completely happy bit of Mahler, there’s always some sadness there, but I wasn’t sure about Strauss. So being moved by that and finding this is genuinely moving music – I mean, Heldenleben, by the time you get to the end of that, there’s this marvellous feeling of things floating and disappearing into some upliftingly spiritual music. I always feel slightly hounded by these dead composers who don’t give up the ghost, and you’re sitting there alone for so many hours and hours with these black notes, and thinking "why is it saying that there, and where’s that come from?" They’re messing about with us in a way if you let yourself into it. Mahler had sidetracked Strauss for me recently and I had to beg forgiveness and say "actually this is bloody good stuff." It would have been quite nice if he’d really wanted to have shaken us rather than being slightly sugary on the surface.

Well, there are the commissions which don’t always seem to serve a purpose.

I bought them all recently, I thought, "off we go, let’s have a look at this lot." I haven’t got very far. It’s actually Schlagobers [the "whipped cream" ballet for Vienna] that took my fancy: we’re going to do that next year. It’s funny, but it’s very nicely done.

In terms of the Bamberg sound, do you think you’ve moulded it to something you had in mind, or is it just a case of a different sound for each piece?

Ah, that’s an interesting question. When I first came I was stepping into a very big pair of shoes, a big tradition of which I was made painfully aware of, but it had been running its course without being constantly worked at. I didn’t want to destroy this sound at all, but more and more I’ve aimed at singing quality. It’s got to be the beauty of sound, which is much richer if you put things on top of the lower than if you blast things out from the top, then gesture-wise it’s much easier to fill things out. Can you hold sound in your hand as a conductor? You definitely can. The cantabile has to be a real cantabile, it’s not letting any tension drop between one note and the next, you stick another finger down, everyone’s got to stick a finger down somewhere except a singer, and you can’t let that get in the way of what it is you’re trying to say, otherwise you’ve broken the contact you have with the line. So there was that element of trying to keep the sound going. I hated the idea of marching, even a march has got to be going backwards or forwards, so it’s more Carlos Kleiber for me than – perhaps his dad [Erich]. So I was anxious that we should feel the music is going somewhere architecturally, even if it’s five minutes off, or coming away from, and not just staying still, so I was trying to get them more flexible from my point of view. Also seeing things harmonically or over a longer span, getting rid of the bar lines – the bigger picture really. That’s what I try to keep going so that when I leave they don’t say, "oh, he ruined us."

Then the other thing is to be unlike the '60s where you basically found one sound that served for all repertoire. Now, I want a sound for Schubert – we keep performing the Unfinished, I do it a little bit faster than I did on the recording, but the idea that you say something with the first foot, there’s a seamless line, not gushing away but over the bar lines, with the right sound colour and where you’re going to put it. If I’m doing Haydn, or Cosi with baroque bows, I don’t want it to sound like bad '60s Mozart, we’re not having that any more. Each epoch should get its own colour, and if you’re doing a programme where these epochs are being fitted into one another, that means an amazing amount of skill and versatility – I have done it, haven’t got it with the winds, but certainly done it with the brass and the strings, they’ll have a different instrument or change the bows. That’s basically a flexibility in that element. But if I go back and, say, listen to Horst Stein’s recording of the Alpine Symphony, I recognise the same orchestra. I haven’t ruined it in that sense.

What would you describe as its main characteristics?

Two things, basically. When they moved here they always played in the old church before the concert hall was built, and it had a very big acoustic, so you’re constantly aware of the resonance coming back at you. And that in my experience divides orchestras and musicians into two halves – those who only really think about the attack, and those who think "what’s coming back at me?", and when you think of that you start to manipulate the sound to make it sound beautiful, which means naturally you have a deeper character. So I am constantly telling them I want more third trumpet than first, and I want more bass in the strings. Why are the first violins going especially loud in a crescendo? No, I want the basses – you can’t go any louder than them. You root things deep, that was something they had, this ability to listen to sound. And then they always wanted to say something, you feel them wanting to play music, which is terribly exciting and makes that a great instrument to play. And if I beat the shit out of the next bit, they beat the shit out of it too. There’s no tussle.

And now I do notice that there’s an ability to move, like a potter with the clay, to just form this music-making and this sound in real time. Which means that rehearsing is getting people to listen to each other, then working out the structure, and roughly how are we going to do this, I’ll break it down into 10 options, I’m not going to break it down to one, so that then each performance can be playing with these 10 options, which keeps the thing alive, which is part of what they wanted to do. Which is not always the case. You sometimes get an orchestra which you feel wants to keep its own personality or preserve something, are rigid and protective of something, and this idea of just letting go and why are these people here, what have I got to say to them and why? And I think that has a lot to do with this place. It is a small place, it’s a rather beautiful place (above, the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra in the Rosengarten), it’s a place where classical music is cherished, where you feel you do belong to society, you meet someone from the audience in the baker’s and they say, that was a good solo you played last night, you feel as if it’s not elite, it’s bread and butter.

And now I do notice that there’s an ability to move, like a potter with the clay, to just form this music-making and this sound in real time. Which means that rehearsing is getting people to listen to each other, then working out the structure, and roughly how are we going to do this, I’ll break it down into 10 options, I’m not going to break it down to one, so that then each performance can be playing with these 10 options, which keeps the thing alive, which is part of what they wanted to do. Which is not always the case. You sometimes get an orchestra which you feel wants to keep its own personality or preserve something, are rigid and protective of something, and this idea of just letting go and why are these people here, what have I got to say to them and why? And I think that has a lot to do with this place. It is a small place, it’s a rather beautiful place (above, the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra in the Rosengarten), it’s a place where classical music is cherished, where you feel you do belong to society, you meet someone from the audience in the baker’s and they say, that was a good solo you played last night, you feel as if it’s not elite, it’s bread and butter.

Germans mostly don’t have the problem of perceived elitism we have in the UK.

No, we lost that a bit, and I hope we find a way – I say "we", Christ, I’ve spent more than half my life away from home, my family’s still there – I don’t feel entirely a stranger, I’ve conducted nearly all the London orchestras now, over the past 15 years. But Europe, the world, it’s a big place, I don’t get home often.

It feels odd me coming and talking to you here. You’re respected in the UK for what you’ve done, but you’re not greatly known there.

I am possibly half to blame for that. If you really go for it – you’re given a chance, as a conductor, of showing off in every bar, and there are people who love doing that. I like showing off but I feel there’s a pull in me between the striptease artist and the librarian. Personally I like to have done a good job, you have to take it seriously, and recreate the fire and flame of when this was a white piece of paper and the composer wrote [sings the opening of Beethoven’s Fifth] and you think, Christ that was amazing to write. I keep buying these facsimiles because it’s fascinating to think…this piece of paper was white and Wagner comes and writes this Tristan chord and you think, "that changed history, did he know what he was writing there?" But also trying to do genuinely what it says there, rather than what might be easier to do or what you’d like to do, is something else. So getting the balance right isn’t easy, but I think we’re getting there.

Overleaf: watch Nott conducting a complete performance of Strauss's Also sprach Zarathustra

Jonathan Nott conducting the Gustav Mahler Jugendorchester in Strauss's Also sprach Zarathustra at the 2009 Proms

Add comment