In amongst the heavy-hearted duty of supporting orchestras by watching their concert streamings – not something I’d do by choice – there are two real joys here. One is the discovery of Austrian composer Franz Schreker’s Chamber Symphony of 1916. The other is witnessing the London Symphony Orchestra's co-principal oboist Juliana Koch playing to an audience – obviously not a group of lucky people sitting upstairs, as we were allowed to do in better times, but her fellow players, most of whom she’s allowed to face, thanks to the special distribution of the LSO in St Luke's.

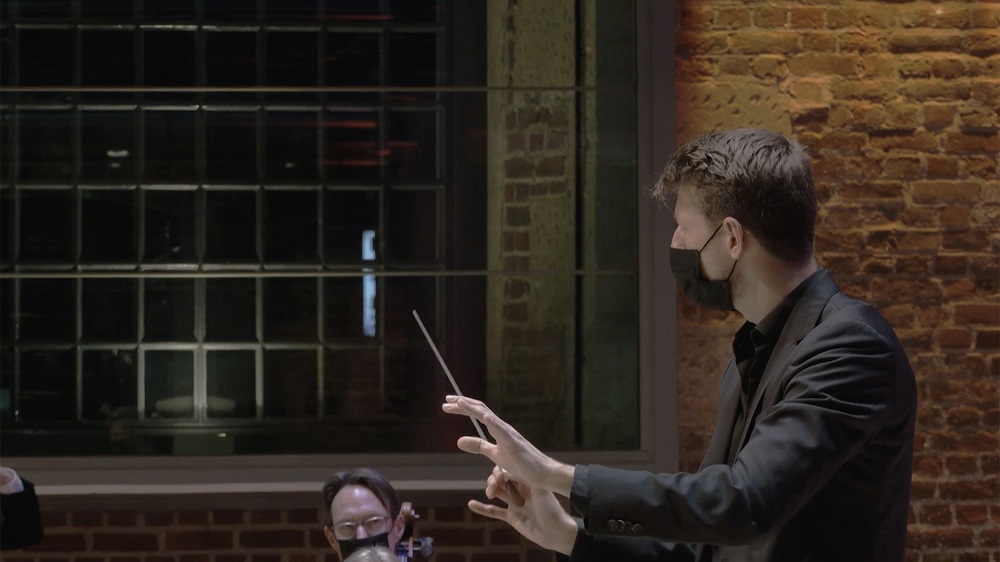

Koch’s is, in any case, the most vibrant and communicative interpretation of the only familiar work in the first of these concerts, conducted with obvious sympathy and suppleness by Duncan Ward (pictured below. My apologies that the seven-day viewing for free which still pertains to the second concert is over, but it’s worth the subscription). While he gives space to the glowing orchestral themes, the oboist’s tour de force shows the effort of those non-stop 56 bars' playing at the beginning, but in a good way, and she toys with every possible freedom when she can, especially in the two cadenzas. Lovely interplay, too, with her woodwind colleagues. And in a beautiful delivered summary of the work’s genesis to Ward before the performance, Koch reminds us that it was a generous peace gesture from the old composer to 24-year-old American oboist John de Lancie, who had been among the troops securing his home town of Garmisch after World War Two was over.  The late-spring beauty of the work comes as balm after the tough, deliberately uningratiating rigour of Polish composer and violinist Grażyna Bacewicz’s Concerto for Strings, Trumpets and Percussion. Here the scars of war seem still raw in 1958; while Strauss was able to stay home, Bacewicz had to get out of Warsaw after the uprising. It’s good to give this unorthodox work an airing at the beginning of a concert programme, and while the material is maybe not first-rate, there’s special interest in the scoring for the five trumpets. Schreker’s late-romantic dreamscapes add another dimension in the triptych; the bewitching initial incantation returns to punctuate the contrasts of luscious slow-movement elements and bucolic scherzo-like writing with delicious woodwind solos. A far cry from the embattled lines of Schoenberg’s First Chamber Symphony of a decade earlier, where harmony is at breaking point, it sometimes seem to cry out for a 100-piece orchestra; but what it does achieve in its demands for the 23 players is idiosyncratic indeed. Ward seems in full accord with its special sound world and its plentiful rubatos.

The late-spring beauty of the work comes as balm after the tough, deliberately uningratiating rigour of Polish composer and violinist Grażyna Bacewicz’s Concerto for Strings, Trumpets and Percussion. Here the scars of war seem still raw in 1958; while Strauss was able to stay home, Bacewicz had to get out of Warsaw after the uprising. It’s good to give this unorthodox work an airing at the beginning of a concert programme, and while the material is maybe not first-rate, there’s special interest in the scoring for the five trumpets. Schreker’s late-romantic dreamscapes add another dimension in the triptych; the bewitching initial incantation returns to punctuate the contrasts of luscious slow-movement elements and bucolic scherzo-like writing with delicious woodwind solos. A far cry from the embattled lines of Schoenberg’s First Chamber Symphony of a decade earlier, where harmony is at breaking point, it sometimes seem to cry out for a 100-piece orchestra; but what it does achieve in its demands for the 23 players is idiosyncratic indeed. Ward seems in full accord with its special sound world and its plentiful rubatos.

A second trilogy of orchestral works with more obvious connections, championed by John Eliot Gardiner, gives us maybe too much of a good thing in folk-style fantasias by Bartok and Ligeti. The Bartok Dance Suite has already made an appearance in this St Luke’s streaming series, under Kerem Hasan, when it felt bigger and splashier; it seems an indulgence to reassemble a large orchestra, two pianos included (one this time an upright) and brass in the galleries. Gardiner’s lean, incisive way doesn’t quite rise to wildness in the final melee, but there are distinguished solos along the way. Even more so in Ligeti’s early Romanian Concerto, where leader Carmen Lauri excels in folk fiddling and the two horns, Timothy Jones and Angela Barnes, provide proto-Ligetian magic after the more conventional early stages.  Gardiner, in typically eloquent introductions, points out the folk connection in Haydn’s drone-bass and rustic melody for the finale of his last symphony, the “London”, No. 104. You feel he might have liked all the players who could to stand, as they did in his Barbican Mendelssohn and Schumann symphonies, and in a performance of the Haydn I was lucky to attend live from the City of London Sinfonia in Southwark Cathedral last November. The presentation here looks more sober than it sounds; the beautifully-nuanced slow movement and Minuet might best be heard and not seen (masks for strings don’t let you see much of the joyous interplay necessary in this symphony). Still, it’s vintage Gardiner in its focused vivacity and guttiness, and another of those select works to make one feel genuinely happy in dark times.

Gardiner, in typically eloquent introductions, points out the folk connection in Haydn’s drone-bass and rustic melody for the finale of his last symphony, the “London”, No. 104. You feel he might have liked all the players who could to stand, as they did in his Barbican Mendelssohn and Schumann symphonies, and in a performance of the Haydn I was lucky to attend live from the City of London Sinfonia in Southwark Cathedral last November. The presentation here looks more sober than it sounds; the beautifully-nuanced slow movement and Minuet might best be heard and not seen (masks for strings don’t let you see much of the joyous interplay necessary in this symphony). Still, it’s vintage Gardiner in its focused vivacity and guttiness, and another of those select works to make one feel genuinely happy in dark times.

- Watch these concerts on Marquee TV. LSO/Gardiner is free to view for the next week; LSO/Ward requires a subscription. Full details on the LSO's website

- More classical music reviews from theartsdesk

Add comment