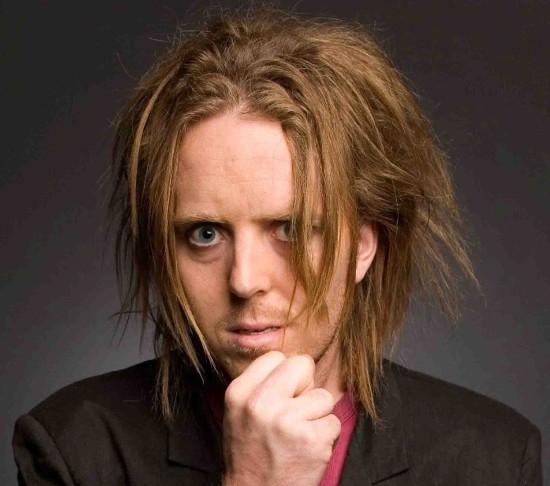

Tim Minchin, the Australian minstrel comedian, is known by his catweazel hair, thickly kohled eyes and dazzlingly witty songs bashed out at a grand piano about, among other things, the debatable existence of the Almighty. Lately his repertoire of tricks has been expanding. He has toured his show with a full orchestra, he wrote the songs for the RSC's rapturously received stage adaptation of Roald Dahl's Matilda (which comes to the West End this autumn) and on Saturday he is hosting the first ever Comedy Prom. Resuming theartsdesk's series featuring the summer reading habits of significant figures from the world of arts and culture, Minchin tells us about the books he has been, is and will be reading.

I’m halfway through Hocus Pocus. I just can’t believe it’s taken me this long to read it. I’m such a Vonnegut head that I’ve swum right down to the books that you have to say are not as good as Slaughterhouse 5 or Cat’s Cradle. But Hocus Pocus is as good, I reckon. He’s just so fucking amazing. Everyone should read Vonnegut. I read his last book, his collected unfinished stuff, a year after he died and halfway through was just hit by this loss that he wasn’t around any more. I never feel that. He’s so casually brilliant.

I’m halfway through Hocus Pocus. I just can’t believe it’s taken me this long to read it. I’m such a Vonnegut head that I’ve swum right down to the books that you have to say are not as good as Slaughterhouse 5 or Cat’s Cradle. But Hocus Pocus is as good, I reckon. He’s just so fucking amazing. Everyone should read Vonnegut. I read his last book, his collected unfinished stuff, a year after he died and halfway through was just hit by this loss that he wasn’t around any more. I never feel that. He’s so casually brilliant.

[From Hocus Pocus by Kurt Vonnegut (Vintage Classics)]

Just because some of us can read and write and do a little math, that doesn’t mean we deserve to conquer the universe.

I don't know why it’s Saturday by Ian McEwan. I don’t think it’s his most broad, sweeping book but it’s just so well constructed. I just love the way he writes. That says something about me. He’s like me. He’s quite logical. Atonement is not a book I like. People say of Saturday, "No one thinks like the protagonist." He’s a surgeon who is constantly analysing everything. It starts like all McEwan’s books, with an event. It was incredibly prescient actually because he predicts not if it will come but when it will come, the terrorist attack. I can’t quote it directly but he says something like, “Will it come in a twist of metal underground?” He’s also wondering whether we should be going into a war with Iraq before it became clear that it was such a fucking beat-up.

[From Saturday by Ian McEwan (Vintage)]

He was behind with his assignments from Daisy. With one toe occasionally controlling a fresh input of hot water, he blearily read an account of Darwin's dash to complete The Origin of Species, and a summary of the concluding pages, amended in later editions. At the same time he was listening to the radio news. The stolid Mr Blix has been addressing the UN again - there's a general impression that he's rather undermined the case for war. Then, certain he'd taken in nothing at all, Perowne switched the radio off, turned back the pages and read again. At times this biography made him comfortably nostalgic for averdant, horse-drawn, affectionate England; at others he was faintly depressed by the way a whole life could be contained by a few hundred pages - bottled, like homemade chutney. And by how easily an existence, its ambitions, networks of family and friends, all its cherished stuff, solidly possessed, could so entirely vanish. Afterwards, he stretched out on the bed to consider his supper, and remembered nothing more. Rosalind must have drawn the covers over him when she came in from work. She would have kissed him. Forty-eight years old, profoundly asleep at nine thirty on a Friday night - this is modern professional life. He works hard, everyone around him works hard, and this week he's been pushed harder by a flu outbreak among the hospital staff - his operating list has been twice the usual length.

He was behind with his assignments from Daisy. With one toe occasionally controlling a fresh input of hot water, he blearily read an account of Darwin's dash to complete The Origin of Species, and a summary of the concluding pages, amended in later editions. At the same time he was listening to the radio news. The stolid Mr Blix has been addressing the UN again - there's a general impression that he's rather undermined the case for war. Then, certain he'd taken in nothing at all, Perowne switched the radio off, turned back the pages and read again. At times this biography made him comfortably nostalgic for averdant, horse-drawn, affectionate England; at others he was faintly depressed by the way a whole life could be contained by a few hundred pages - bottled, like homemade chutney. And by how easily an existence, its ambitions, networks of family and friends, all its cherished stuff, solidly possessed, could so entirely vanish. Afterwards, he stretched out on the bed to consider his supper, and remembered nothing more. Rosalind must have drawn the covers over him when she came in from work. She would have kissed him. Forty-eight years old, profoundly asleep at nine thirty on a Friday night - this is modern professional life. He works hard, everyone around him works hard, and this week he's been pushed harder by a flu outbreak among the hospital staff - his operating list has been twice the usual length.

I don’t read non-fiction easily but I must - I want to as I get older. I’ve never read a book of Timothy Garton Ash's. He’s just one of these people that I’ve heard on podcasts and go, wow, you’re really fucking right about shit. I tend to be seduced by intelligence to the extent that, like all people, I should be careful because I don't know enough to be critical. Facts Are Subversive is about Eastern European politics and I can’t tell you the gaps in my knowledge of history, geography and politics. There’s nothing but gaps. I just didn’t ever do any of those subjects. I’ve always been English and poems and shit, so I’m trying to rectify it. Someone invited me to do Celebrity Mastermind. I was like, "No, I’ve managed to sell this idea that I’m quite bright and I don't know stuff."

I don’t read non-fiction easily but I must - I want to as I get older. I’ve never read a book of Timothy Garton Ash's. He’s just one of these people that I’ve heard on podcasts and go, wow, you’re really fucking right about shit. I tend to be seduced by intelligence to the extent that, like all people, I should be careful because I don't know enough to be critical. Facts Are Subversive is about Eastern European politics and I can’t tell you the gaps in my knowledge of history, geography and politics. There’s nothing but gaps. I just didn’t ever do any of those subjects. I’ve always been English and poems and shit, so I’m trying to rectify it. Someone invited me to do Celebrity Mastermind. I was like, "No, I’ve managed to sell this idea that I’m quite bright and I don't know stuff."

[From Facts Are Subversive: Political Writing from a Decade Without a Name by Timothy Garton Ash (Atlantic Books)]

One of Germany’s most singular achievements is to have associated itself so intimately in the world’s imagination with the darkest evils of the two worst political systems of the most murderous century in human history. The words “Nazi”, “SS”, and “Auschwitz” are already global synonyms for the deepest inhumanity of fascism. Now the word “Stasi” is becoming a default global synonym for the secret police terrors of communism. The worldwide success of Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s deservedly Oscar-winning film The Lives of Others will strengthen that second link, building as it does on the preprogramming of our imaginations by the first. Nazi, Stasi: Germany’s festering half-rhyme.

It was not always thus. When I went to live in Berlin in the late 1970s, I was fascinated by the puzzle of how Nazi evil had engulfed this homeland of high culture. I set out to discover why the people of Weimar Berlin behaved as they did after Adolf Hitler came to power. One question above all obsessed me: what quality was it, what human strain, that made one person a dissident or resistance fighter and another a collaborator in state-organised crime, one a Claus von Stauffenberg, sacrificing his life in the attempt to assassinate Hitler, another an Albert Speer?

I soon discovered that the men and women living behind the Berlin Wall, in East Germany, were facing similar dilemmas in another German dictatorship, albeit with less physically murderous consequences. I could study that human conundrum not in dusty archives but in the history of the present. So I went to live in East Berlin and ended up writing a book about the Germans under the communist leader Erich Honecker, rather than under Adolf Hitler. As I travelled around the other Germany, I was again and again confronted with the fear of the Stasi. Walking back to the apartment of an actor who had just taken the lead role in a production of Goethe’s Faust, a friend whispered to me, “Watch out, Faust is working for the Stasi.” After my very critical account of communist East Germany appeared in West Germany, a British diplomat was summoned to receive an official protest from the East German foreign ministry (one of the nicest book reviews a political writer could ever hope for) and I was banned from re-entering the country.

Add comment