Music of Today - November: Sonica, HCMF, Oliver Knussen, the Arditti Quartet and Heiner Goebbels | reviews, news & interviews

Music of Today - November: Sonica, HCMF, Oliver Knussen, the Arditti Quartet and Heiner Goebbels

Music of Today - November: Sonica, HCMF, Oliver Knussen, the Arditti Quartet and Heiner Goebbels

New monthly survey of the latest developments in contemporary sound and music

Arditti String Quartet, Wigmore Hall, 31 October ****

November is always a good month for new music. This year saw the interest begin a day earlier. Whichever wag chose to hand over Halloween at the Wigmore Hall to two of the most uncompromising contemporary string quartets, however, was denied a fitting punchline. The young JACK Quartet were grounded in New York by Sandy, and the venerable Ardittis chose to programme works that weren't half as terrifying as hoped.

Mauro Lanza's new octet was to see the upstart quartet perform with the old pros. Without the JACK's, however, we got Wolfgang Rihm's String Quartet No 13 (2011). A work of what the programme notes suggested would be a precisely notated and computer-derived chaos was swapped for one of uncomplicated and unabashed neoromanticism. Playing to convention, Rihm told a story and told it well. The Ardittis showed that they could construct as well as deconstruct. And the concert ended warmly and safely. Which belied where we had begun.

In Saunder's Fletch what starts off as an exercise in description moves into something much more feeling and interior

James Clarke's String Quartet (2002-3), which opened the night, is a self-contained and self-sustaining work that spits fire like a catherine wheel. Here, there was no feeling of being shortchanged (we were originally meant to hear a Clarke UK premiere for two string quartets, 2012-S). The balletic team-work of the opening, which used the glissando as a building block, was very Merce Cunningham - full of stiff arms, tensed legs and sudden sweeps. Clarke explores this formal but intense dance for two thirds of the work's length then allows the piece to atrophy and split apart through repetitive wear and tear. And, just as one was becoming weary with the patterning, the work crumbles to a ravishing end.

Formally Rebecca Saunders' Fletch (2012) was similar, avoiding ennui by a judicious change of tack. In Saunders the shift was emotional. What starts off as an exercise in extended technique and description - the flight of a fletched arrow delivered in stabs sul ponticello - moves into something much more feeling and interior. And as we burrowed deeper into this world - the cello and violas detuning their instruments mid-performance - Saunders also frees herself of both metaphor and influence and begins to explore more bleak and interesting territory.

The most straightforward work, the Hans Abrahamsen Fourth String Quartet (2012) (which was being given its UK premiere) was the most affable but the least memorable of the four works. Too many of the movements (the only one on the programme to offer divisions in this way) resembled other styles: Messiaen in the first movement, Copland in the last. Still, in the hands of the Ardittis, the hocketing in the second movement and the pizzicato passacaglia of the third meant a pretty enjoyable time could still be had.

Where the Wild Things Are/ Higglety Pigglety Pop!, Barbican Hall, 3 November **

Total Immersion: Oliver Knussen At 60, Barbican Centre, 4 November ***

Far more terrifying - in an embarrasing kind of way - than the neomodernism of the continent is the polite academicism of so much British music. Oliver Knussen is one of the high priests of this style. The Barbican weekend focus began with the weakest corner of his output, his two one-act operas Where the Wild Things Are (1979-1983) and Higglety Pigglety Pop! (1984-5, rev. 1999), which exemplify Knussen at his most technically efficient, highly refined but also forgettable. The basics didn't help. Why anyone would attempt to mess around with a children's story that many consider a masterpiece is beyond me. Maurice Sendak's book was unfurled at a pace that even the children around me were finding simple-minded. In the process the simple story of Max (a fabulously boyish Claire Booth) who lets his imagination run wild becames quite grotesquely boring. Only great music could have rescued the work from its longueurs. But, save a few magical choruses, the score was not much cop.

Director Netia Jones had the toughest job of the night, trying to re-visualise something that has already been so perfectly visualised. Understandably she chose not to fiddle too much with the basics and instead met Sendak half way, projecting an animated version of his colour drawings onto large screens [pictured right]. It didn't work for me. It was too literal, too safe and too removed from what was going on in the pit. But neither did it seem to work for the children in attendance either. None seemed very chipper. Their ears pricked up only once, during the interval when a box of perfectly cut, white, triangular sandwiches arrived at front of the stage for the second Knussen opera. Higglety Pigglety Pop! was, however, even more unbearable than Where the Wild Things, mostly becuase it was impossible to understand what was going on.

Director Netia Jones had the toughest job of the night, trying to re-visualise something that has already been so perfectly visualised. Understandably she chose not to fiddle too much with the basics and instead met Sendak half way, projecting an animated version of his colour drawings onto large screens [pictured right]. It didn't work for me. It was too literal, too safe and too removed from what was going on in the pit. But neither did it seem to work for the children in attendance either. None seemed very chipper. Their ears pricked up only once, during the interval when a box of perfectly cut, white, triangular sandwiches arrived at front of the stage for the second Knussen opera. Higglety Pigglety Pop! was, however, even more unbearable than Where the Wild Things, mostly becuase it was impossible to understand what was going on.

In Songs For Sue, Knussen honours the poetry of Dickinson, Machado, Auden and Rilke, clearly, simply, movingly and dazzlingly

Stepping back and taking an overview of the Knussen ouevre - as one was able to do the next day in the Barbican's Total Immersion series - and there seemed several ways of making sense of the composer's career. One could either see it as very small, very hit and miss, or remarkable for the handful of genuine masterpieces it contains. His earliest works were fascinating in their descriptive precision and focus of thought. Three Little Fantasies (1970, rev.1983), delivered very nicely by the Guildhall New Music Ensemble, were particularly delicious, as was his soprano and chamber piece Ocean de terre (1972-3, rev. 1976), which uses percussion with precocious maturety (Knussen was only 20 when he started it) to evoke a series of Apollinairian poetic images.

The later works (mostly solo piano or piano and violin) lose their way a bit through attempting to be ever cleverer, more complicated and refined. That said, the day ended with two corkers: the celebrated Horn Concerto (1994, rev. 1995) and Knussen's masterpiece, Requiem - Songs for Sue (2005-6). The concerto, excellently despatched by Martin Owen, is based on familiar musical furniture yet it retains a distinctiveness in its bouyant and addictive descending figures. In Songs For Sue, Knussen honours the poetry of Emily Dickinson, Antonio Machado, Auden and Rilke, clearly, simply, movingly and dazzlingly. To hear Claire Booth deliver these under the helm of Knussen himself, who was conducting the BBC Symphony, was worth the whole weekend.

Heiner Goebbels' Stifters Dinge, Ambika P3, Artangel, 4-18 November ****

If we began the month in pretty conventional concert hall settings, we spent most of the rest of the season in increasingly strange locations. One can't yet make a rule that the further from 18th century-type halls you get the better the new music will be. But, certainly, the further from the institutions you go, the freer, more imaginative and varied the possibilities and results will probably be. Heiner Goebbels' Stifters Dinge - returning to the cavernous former motorway-making factory in Marylebone, Ambika P3, courtesy of Artangel - is a case in point. Few concert halls or opera houses know what to do with Goebbels' multimedia installations. So, like so much of the best new opera today, they're hoovered up by enterprising production companies in the visual arts.

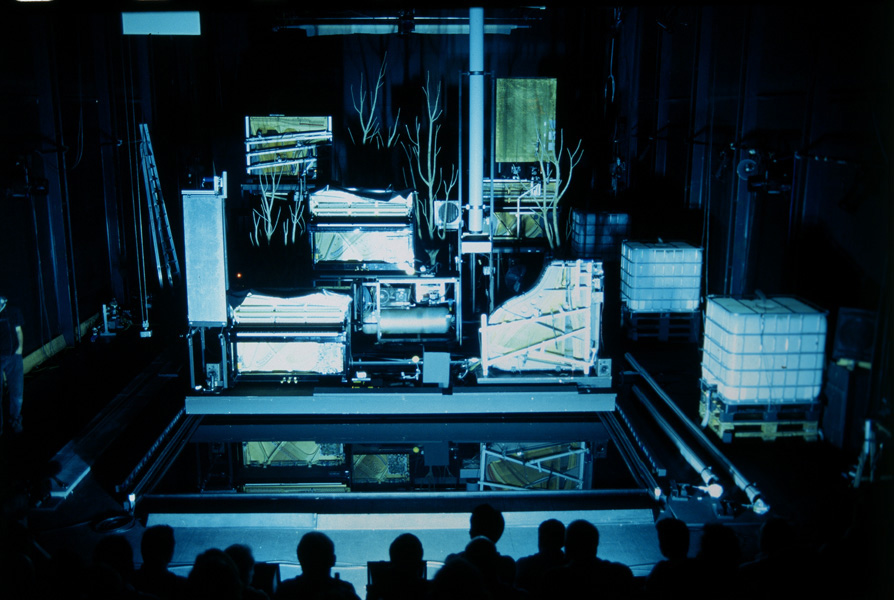

This time the vast self-generating mechanical musical theatre that is Stifters Dinge [pictured left: photograph by Mario del Curto] was now both an art installation that played out its mysterious ritual - in which three pianos divested of their glossy wooden skins and planted amid trees stalk three pools of water - over the course of the whole day as well as in evening performances. Having seen the curated evening events twice in the past, I explored the day event. There were loses and gains. You lost the taut dramatic form that allowed the concatenation of events in the evening concert to amaze and beguile and fill one with awe. You lost - if you came early in a cycle - the mysterious words of Adalbert Stifter and sundry others, which in performance adds a thinking rather than purely visceral narrative to the evening. And you lost some of the mystery as the murky excretions of sound revealed themselves more as you walked around each sound-producing object.

This time the vast self-generating mechanical musical theatre that is Stifters Dinge [pictured left: photograph by Mario del Curto] was now both an art installation that played out its mysterious ritual - in which three pianos divested of their glossy wooden skins and planted amid trees stalk three pools of water - over the course of the whole day as well as in evening performances. Having seen the curated evening events twice in the past, I explored the day event. There were loses and gains. You lost the taut dramatic form that allowed the concatenation of events in the evening concert to amaze and beguile and fill one with awe. You lost - if you came early in a cycle - the mysterious words of Adalbert Stifter and sundry others, which in performance adds a thinking rather than purely visceral narrative to the evening. And you lost some of the mystery as the murky excretions of sound revealed themselves more as you walked around each sound-producing object.

Gains, however, were to be made in this switch from concert hall environment to zoo, where you were able to examine and inspect and linger. Respect and intrigue increased as you got to understand the details. The changes of dramatic tack were all the more arresting after an hour in a certain groove. The music appeared in dribs and drabs and spits and spurts as sound does in the real world. When the pianos wanted to talk, they talked. Plucked strings and popped pipes added a instecty cloud of sound to the mix. Rarely has music or theatre come so close to being a living, breathing, sounding being.

To Dream, Not To Sleep, East 15 BA Acting and Contemporary Theatre, Hackney *****

Opera began life with the word predominant. Prima le parole was a common cry from purists of the first two centuries. The past 300 years has seen music's ascendancy. But there are signs today from the experimental fringes that the brother arts - poetry and dance - are returning. Choreography was at the heart of one of the best new short experimental operas of the past month. To Dream, Not To Sleep, from artistic partners Melanie and Alexander Lomoff-Zeldin, was presented modestly at a community hall in Hackney and announced as a work in progress. Yet it had more of a fully fleshed out sense of itself, what it wanted to say and how it aimed to say it than most of what passes for opera today.

Channelling the elliptical choreographical art of Robert Wilson, where the everyday gesture is invested with memorable new purpose, the Lomoff-Zeldins offer up a school day: visits to the bathroom, classroom, sports hall, playground, a round of hop-scotch. There are no props, no music, save some vocalising from the actors. What we get instead is half an hour of carefully composed gesturing and miming, ruptured periodically by moments of distress, anger or suffocation. The imagination was impressive, the voice clear, the story non existent, the result deeply affecting.

SONICA, GLASGOW

Our Contemporaries, Mookyoung Shin, Tramway, 9-18 November ****

Remember Me, Claudia Molitor, Scotland Street School Museum, 8, 14 and 15 November *

Bluebeard, 33 1/3 Collective, Sonica, Tramway, 14-18 November ***

Tales of Magical Realism - Part 2, Sven Werner, Tramway, 14-17 November **

Extended Play, Janek Schaefer, 8-15 November ****

Enlightened Sound, The Whisky Bond, 27 October - 18 November ****

Piano Migrations, Kathy Hinde, Scottish Music Centre, 19 October - 18 November *****

With some of the best operatic experiences emerging from the confluence of new technology, visual arts, immersive theatre and new music, Sonica, a new Glasgow-based music festival dedicated to exploring this experimental no-man's land, is a hugely welcome addition to the scene. Its first offerings were fascinating. The further from the conventional musical experience we went, the better time was had. Even those things that didn't deliver, however, offered something. In Sven Werner's elaborate and somewhat twee Gothic mystery Tales of Magical Realism - Part 2 (2012) that take-away moment was being followed through a disused warehouse, up stairs and through corridors, by two choirs girls dressed in Victorian dress while they sang Swedish hymns in our ears. Acoustically speaking, unforgettable.

Kathy Hinde's Piano Migrations was a simple illusion but an absolutely mesmerising oneThe virtuosity of the film-making of video collective 33 1/3 in their tromp l'oeil presentation of the tale of Bluebeard was frequently extraordinary too. There's plenty for the film-makers to do in Bluebeard, as a woman's desire to know what's lurking behind the doors of the castle of her lover leads her into darker and darker territory. Legs fall from the sky, flesh is cut, blood is poured, bodies are shovelled. As story-tellers they lacked the ability to make anything hugely significant out of this episodic tale but as film-makers, they had a lot to offer. Little could rescue Claudia Molitor's solo performance Remember Me (2012), however, an interactive (well, she gives out some chunks of Turkish delight) short anti-opera, taking the female perspective on the the Orpheus and Dido stories and imagining them interacting in the world beyond. This study of male negligence and female boredom was effective only in its ability to bore us.

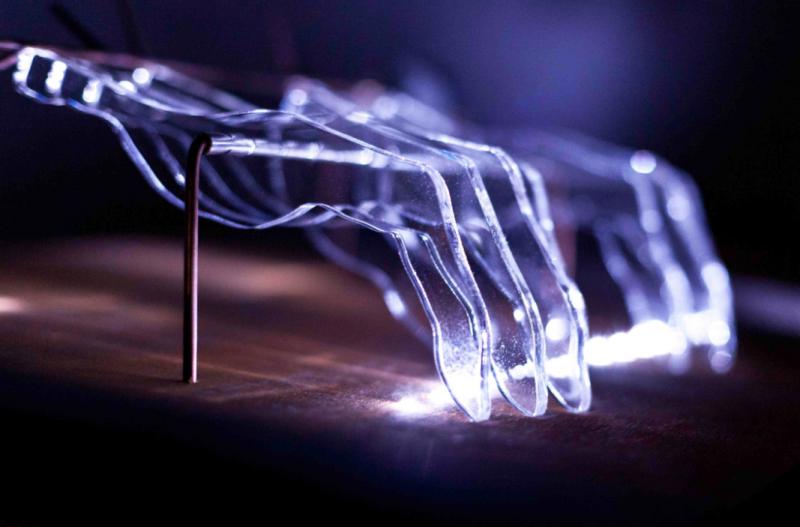

A far more effective crop of works could found among the wealth of new sound art. Mookyoung Shin's Our Contemporaries at the Tramway sees a heady, rhythmic symphony rise up out of the tapping of hundreds of mechanised glass hands. Boredom here is rendered sublime. Elsewhere, in the Whisky Bond, the flight of pigeons across a disused warehouse is magically reconstructed by Steev Livingston. Stretching a tape-looped recording of the pigeons' flight across two playheads and placing the speakers across the empty concrete space, Livingston conjures up a simple but exceptional, poetic event. In another room, Tom Marshallsay and Richard McMaster ask us to examine what good sound might be. Four turntables play various bell and snapped wood sounds. We are invited to stop and shift the playheads as we chose. An excellent investigation of fundamentals.

One of the many threads in the festival was interactivity. The most involving of those pieces that dealt with this element was Janek Schaefer's installation Extended Play (Triptych for the child survivors of War and Conflict). Rearranging a musical phrase from a Polish folk song that had been broadcast during WWII to Poles the day his mother was born, Schaefer took the etherised results and made violin, piano and cello recordings. These were then played on three record players in a room flooded with red light. Some heavy-handed statement-making aside, it was difficult not eventually to succumb to the sombre, reflective atmosphere and the allusions. That the music would stop when visitors approached the record player's space transformed the turntable into a pram and the music into a baby's cries.

One of the many threads in the festival was interactivity. The most involving of those pieces that dealt with this element was Janek Schaefer's installation Extended Play (Triptych for the child survivors of War and Conflict). Rearranging a musical phrase from a Polish folk song that had been broadcast during WWII to Poles the day his mother was born, Schaefer took the etherised results and made violin, piano and cello recordings. These were then played on three record players in a room flooded with red light. Some heavy-handed statement-making aside, it was difficult not eventually to succumb to the sombre, reflective atmosphere and the allusions. That the music would stop when visitors approached the record player's space transformed the turntable into a pram and the music into a baby's cries.

The best work of the festival, however, was an unassuming installation in the foyer of the Scottish Music Centre. In Kathy Hinde's Piano Migrations [pictured above left], a piano becomes a bird cage (or should that be a Cage bird). Projections of birds' silhouettes and the pylons on which they sit flood a vertically hung piano body. As these shadows fly to and from their perch, their movement creates the music, their wings appearing to bang on and brush against the strings, metal and wood of the piano, as if they were playing a prepared piano work by John Cage. A simple illusion but an absolutely mesmerising one.

HUDDERSFIELD CONTEMPORARY MUSIC FESTIVAL (HCMF)

'New' 'Work', Johnny Herbert, Huddersfield Art Gallery 16 November - 25 November *****

Donnacha Dennehy Portrait, Crash Ensemble, Alan Pierson, St Paul's Hall, 16 November **

SPUNK + Palimpsest, Bates Mill, 16 November *****

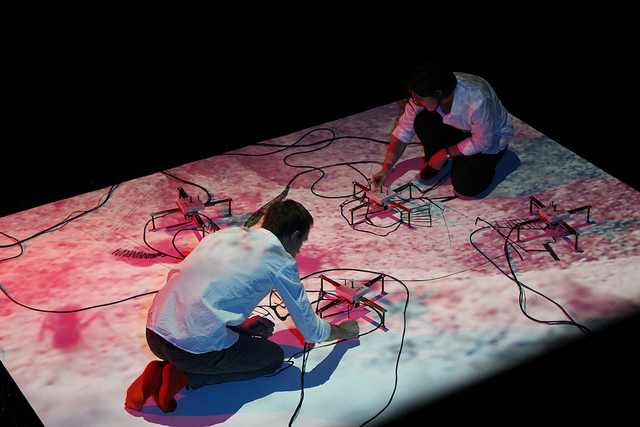

Nicolas Hodges, St Paul's Hall, 17 November ***

Listener interaction, visual mindedness, conceptual freedom, improvisation. While these elements are still negelected by traditional, academic contemporary classical music, Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival revels in them - this year more than ever. Improvisation was the theme of a thrilling late concert on the opening night. Improvisation usually comes at a cost. Freedoms in noise and colour are undermined by constraints in the ability to plan formally. The improvisatory acts that enthralled a small but enthusiastic crowd at the Bates Mill, Huddersfield, on the festival's opening nights, however, belied this rule. In Palimspest (2012) (co-produced by Sonica, and pictured below right) technology, electronica and art intermingle in a fiendishly complicated way to create a living score. As artist Kathy Hinde put down markings on the floor, several revolving compasses scanned across the evolving drawing and convert the lines into live music with help from Daniel Skoglund. A fidgety explosion of feedback noise and beats slowly coalesce into jungly electronica.

Jean Barraque's music was like eating a whole packet of crackers without water

This was followed by an epic set from Norwegian musical polymath, Maja S K Ratkje, and the SPUNK musical collective. The source of this ecstatic alchemy was difficult to pin down. Ratkje sang, her collective adding horn, trumpet, cello and recorder timbres to the mix, and with this a cloud of sound would emerge, each element being washed out or chopped up by Ratkje's electronic manipulations. Behind her and her ensemble Len Lye-like live video abstractions from Andreas Paleologos embraced the textural fluctuations and celebrated a world of pixellated lo-tech beauty. Ratkje's musical imagination was intense and vast, the control of form incredible. She steered the hour-long activity as cleverly and captivatingly as a great 19th century symphonist.

By comparison, the messy, ampilified, postminimalism of Irish composer Donnacha Dennehy - a selection of whose music we heard in the opening concert from the Dublin-based Crash Ensemble - could not compete. Nor could the virtuousity of Nicholas Hodges's performance of the at times fiendishly complicated piano works of the neglected (probably not unfairly) mid-century modernist Jean Barraque, listening to whose music was like eating a whole packet of crackers without water.

Whether by chance or design, many of the best new sound works of 2012 have looked back to the example of Cage. Johnny Herbert's neodadaist installation 'New' 'Work' (2012) at the Huddersfield Art Gallery delivered some of the most profound results with the most audaciously economical means. A dozen instruments and sounding objects - piano, electric guitar, gong, radio, metronome, pen and paper with microphone etc - were arranged in a circle. Empty chairs were placed beside them. Visitors were let into the room and invited to do as they pleased.

Herbert's framing device - whereby visitors clocked in and clocked out and got given a hypthetical minumum wage for their 'work' - was redundant. The work spoke eloquently and volubly and profoundly on its own. The complete freedom it offered led to total re-evaluation of the self and of the creative act. Never have I felt so bullied into thought. Not only does one have to reconstruct what one thinks a performance might be, how it might come about and why one might do it, one is also asked in that moment when you enter the room to examine the basics of what it means to be human.

The eyes of some seemed to express fear. Others seemed to silently ask, are you here to play? Shall I? My initial suspicion and embarrasment towards those plucky strangers who had decided to strike up a rhythm or melody gave way to embarrassment at myself for not playing. What was I doing here if I wasn't going to play. The whole point was that we the visitors - this random collection of drifters who happened to find themselves in Huddersfield Art Gallery on this particular Saturday morning - were the performance. To not perform was to not have a performance. By not playing, I would be creating and self-perpetuating the non existence of the performance. This was a emperor's-new-clothes situation of my own making.

Needless to say every interaction, every decision from every visitor, was priceless. The moment when a brash young woman dropped her shopping, sat at the drum kit and bashed her way with Indie-pop-indifference through the polite Feldmanesque doodling that a group of donnish old men had been building up slowly over half an hour. The man who could deliver anything in any style on any instrument and did. The guy who made music out of the creaky hinges of the piano lid. The shy bloke who sat at a table dropping coins for half an hour.

All the music came in cycles. The start of each set would always be quiet. As others joined in, the focus became sharper, the aim more purposive, the construction complicated, the dynamics bold. Then, mysteriously, an end would come, through boredom or exhuastion or a realisation that one had to catch the train. And, apart from the tick and tock of the clock, for the next three minutes, there'd be silence. No music. No performers. Nothing. And in those silences, the heavy weight of embarrassment and anguish would fall on us. When would one of us pluck up the courage to start the performance again? If they did, what would they play? And if they didn't, what the hell were we doing here? A Beckettian nightmare and compulsive work of genius that nearly made me to miss my train.

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

Comments

I may have missed a link -

Hi, at the bottom of each

Hi, at the bottom of each page is a 'next page' tab which will show you the rest of the review