Snowboy's History of the UK Jazz Dance Scene | reviews, news & interviews

Snowboy's History of the UK Jazz Dance Scene

Snowboy's History of the UK Jazz Dance Scene

Mark Cotgrove's labour of love memorialises a halcyon era

In another lifetime, I walked into the Electric Ballroom in Camden Town through a portal into a new world: the cavernous dancehall was packed, and the "audience" being choreographed by cross-rhythms of Afro-Cuban and Brazilian ancestry in an atmosphere created by a 17-year-old jazz funk DJ called Gilles Peterson. I was witnessing the dawn of the New Jazz Age.

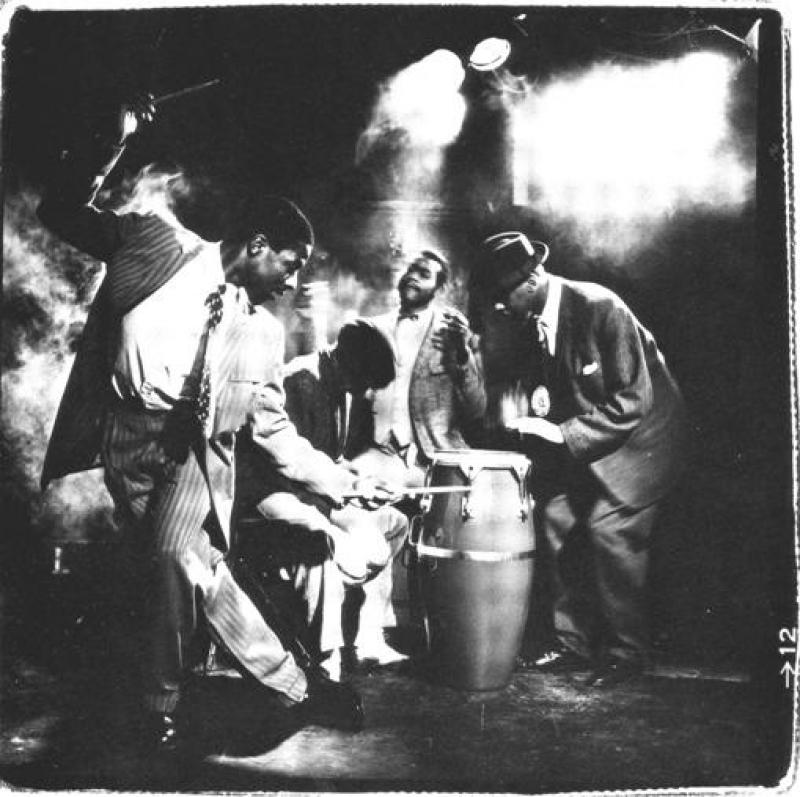

The mostly black dancers wore baggy suits, white shirts and braces like the 1930s jivers at Harlem’s Savoy Ballroom, the Forties mambo-niks at Manhattan’s legendary Palladium Ballroom, and hats like the Jamaican rude boys in (London) Soho’s basements documented by the then newspaper snapper, Ken Russell. It resembled a period-piece film-set and their improvised performances, balletic spins and feet blurred like a tap-dancer’s, were breathtakingly new and exciting.

The mostly black dancers wore baggy suits, white shirts and braces like the 1930s jivers at Harlem’s Savoy Ballroom, the Forties mambo-niks at Manhattan’s legendary Palladium Ballroom, and hats like the Jamaican rude boys in (London) Soho’s basements documented by the then newspaper snapper, Ken Russell. It resembled a period-piece film-set and their improvised performances, balletic spins and feet blurred like a tap-dancer’s, were breathtakingly new and exciting.

Upstairs, in a small room packed like Coney Island beach, another crowd danced to different tunes, chosen for their dominant Latin genes: Azymuth’s samba-fusions, Dizzy Gillespie’s Cubop loaded with Chano Pozo’s ancient conga rhythms, and Herbie Hancock’s disco-funk. The peacock dancers were now driven by a tall, chain-smoking, pale man - the legend of the era, DJ Paul Murphy. For the first time, black youth were the focus of white kids who absorbed their moves, memorised and then imitated their gymnastic spins and rolls and a physical syntax anticipating New York’s imminent hiphop explosion.

So that was my entrée to the UK’s unique jazz dance scene which would become part of my life. It drove me too, to the decks and to obsessive vinyl collecting - on the Latin side. Thirty years later a former Essex soul boy, Mark Cotgrove, has self-published a documentary of the era based on over 250 interviews with the movers and makers of the scene: DJs, jazz dancers, radio presenters, collectors and fans. The result is an important social and cultural documentary.

Today "Snowboy", as Cotgrove became universally known, is the UK’s most respected conga drummer (working with, amongst others, the salsa legend, Eddie Palmieri). He runs his own bands and is an occasional DJ. Using his guests’ descriptions, reminiscences and boasts from that time, he spent a decade piecing together the story, and explains its importance: “It was about time that our unique jazz dance scene and all the DJs and incredibly talented dancers within it are recognised properly for the first time. For such an enormous scene, jazz dance and its predecessor jazz funk, continues to either not get mentioned or barely acknowledged in other music history books…so now I’ve addressed the situation.”

The book opens with Snowboy’s definition of jazz dance: “Not the ‘jazz dance’ of the 1930s in the US,” he explains, “It is a scene that was created here in the UK by innovative DJs daring to play jazz fusion next to the disco, funk, soul and jazz funk releases of the time – inspired (and probably cajoled, in some instances) to play harder grooves and faster tempos by the dancers.”

That symbiotic relationship between DJ and dancer was crucial, and although the two parties often danced metaphorically around each other in interviews, Snowboy emphasises the connection: “From just initially freestyle dancing, the dancers were developing steps to particularly take-on [sic] the increasingly challenging music – which, in turn made the DJs dig up even more records to taunt and tempt them with.” Most memorable are the near-balletic performances of IDJ (I Dance Jazz, who were spectacularly clad in suits, braces and two-tone spats - pictured below), and the more acrobatic moves of Manchester’s Jazz Defektors.

The book is constructed as a series of Q & A interviews, dividing the story geographically around the UK, and ensuring as much space to the music as the dance. It glides from jazz-funk to jazz-dance, into Latin-fusion and on to Gilles Peterson’s Acid Jazz and its birth in Camden’s Dingwalls club, before shooting off into capillaries feeding salsa to other mixed-up tribes. The resulting book is a hugely evocative recreation of an esoteric corner of Britain’s popular music history.

The book is constructed as a series of Q & A interviews, dividing the story geographically around the UK, and ensuring as much space to the music as the dance. It glides from jazz-funk to jazz-dance, into Latin-fusion and on to Gilles Peterson’s Acid Jazz and its birth in Camden’s Dingwalls club, before shooting off into capillaries feeding salsa to other mixed-up tribes. The resulting book is a hugely evocative recreation of an esoteric corner of Britain’s popular music history.

In his foreword, Robert Farris Thompson, Yale Professor of Music and Art from the African disaspora, don of Mambo, voudou priest, and author, describes his friend Snowboy as “the best Brit conguero of them all. With Snowboy”, he adds, “The field [of jazz dance, jazz funk] has found its Homer.” Stretching it a bit, perhaps. But I agree that Snowboy’s own writing is “free of affection or pretence... [he] talks to us in his own level voice, drawing us in.” A more appropriate comparison, I feel, is with the Pulitzer Prize-winning American documentary writer, Studs Terkel, whose magnificent books were similarly constructed from interviews to build a mosaic over-view of his chosen subjects: the American people.

While Terkel’s crafted interviews were accompanied by his own reflective, analytical comments, Snowboy’s style is colloquial, unconcerned with grammatical correctness and, for economic reasons, largely unedited. For him, the story is the thing. Thompson calls the writing “direct, free of affectation, spoken in a level voice which draws us in”. He even likens him to Shakespeare! The book’s value lies in the interviews; it’s more of a dipping book than a cover-to-cover read but, taken as a whole, it offers a marvellous link back into an era which, compared to the endlessly poured-over punk realm, has been poorly documented. The excitement radiating from the pages of reminiscence will make any reader envious of having missed out on a Great Musical Moment.

Accompanying the interviews, black and white photographs reawaken the atmosphere of the clubs and portraits of the interviewees. Particularly strong are the photogenic dance groups who were later imitated in New York and Tokyo, and who appeared in UK pop videos and the universally panned film, Absolute Beginners. Nick White’s black and white photograph of the saxophonist Steve Williamson posing nonchalantly with the trio IDJ in baggy zoot-suits and spats against an old car, is a beautifully moody, self-conscious recreation of early 20th-century Harlem jazz photography by the likes of Roy DeCarava and later by Bob Willoughby.

Alongside the photographs are the flyers and posters designed according to the new jazz look to match music and image. The designer, Swifty, invented new typefaces and layouts which led to international awards. He also created, with Paul Bradshaw, award-winning designs for Bradshaw’s magazine Straight No Chaserwhich became the mouthpiece of the growing international community. Bradshaw also takes the honours for launching the new jazzers’ essential accessory, their floral version of Jamaica’s stingy-brimmed trilby.

He sums up the musical significance of the era: “Music and people were more open-minded: someone who liked jazz fusion would probably like Parliament too. Somehow, all these different forms of black music fitted together… African music, big articles on jazz, deep pieces on fusion, reggae; Little Beaver (the Miami soul guitarist) next to Bob Marley.” Such diversity unarguably laid the foundations for Britain’s uniquely eclectic audiences today.

Having laid his labour of love to bed, and before he could turn back to his congas for relief, he wrote: “I’m glad that all this has been documented at last.”

From Jazz Funk & Fusion to Acid Jazz: The History of the UK Jazz Dance Scene by Mark "Snowboy" Cotgrove (AuthorHouse/ Chaser Publications).

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Emily A. Sprague realises a Japanese dream on 'Cloud Time'

A set of live improvisations that drift in and out of real beauty

Emily A. Sprague realises a Japanese dream on 'Cloud Time'

A set of live improvisations that drift in and out of real beauty

Trio Da Kali, Milton Court review - Mali masters make the ancient new

Three supreme musicians from Bamako in transcendent mood

Trio Da Kali, Milton Court review - Mali masters make the ancient new

Three supreme musicians from Bamako in transcendent mood

Hollie Cook's 'Shy Girl' isn't heavyweight but has a summery reggae lilt

Tropical-tinted downtempo pop that's likeable if uneventful

Hollie Cook's 'Shy Girl' isn't heavyweight but has a summery reggae lilt

Tropical-tinted downtempo pop that's likeable if uneventful

Pop Will Eat Itself's 'Delete Everything' is noisy but patchy

Despite unlovely production, the Eighties/Nineties unit retain rowdy ebullience

Pop Will Eat Itself's 'Delete Everything' is noisy but patchy

Despite unlovely production, the Eighties/Nineties unit retain rowdy ebullience

Music Reissues Weekly: The Earlies - These Were The Earlies

Lancashire and Texas unite to fashion a 2004 landmark of modern psychedelia

Music Reissues Weekly: The Earlies - These Were The Earlies

Lancashire and Texas unite to fashion a 2004 landmark of modern psychedelia

Odd times and clunking lines in 'The Life of a Showgirl' for Taylor Swift

A record this weird should be more interesting, surely

Odd times and clunking lines in 'The Life of a Showgirl' for Taylor Swift

A record this weird should be more interesting, surely

Waylon Jennings' 'Songbird' raises this country great from the grave

The first of a trove of posthumous recordings from the 1970s and early 1980s

Waylon Jennings' 'Songbird' raises this country great from the grave

The first of a trove of posthumous recordings from the 1970s and early 1980s

Comments

...

...

...

...

I knew one of IDJ and he was