Riot music: we should have listened harder | reviews, news & interviews

Riot music: we should have listened harder

Riot music: we should have listened harder

Were we warned?

I'm not claiming some major prescience or insight here. I am as guilty as anyone of dipping into the music of the sink estates for a small dose of frisson then returning to art and music that confirm my own worldview. But maybe, just maybe, if we had all paid more attention to what was being said by young British men and women from those estates over the last decade, the events of the past few days might not have come as such a horrific surprise.

Grime, of course, was and often still is angry music, and it was noted when Dizzee Rascal first exploded onto the scene that his harsh poetry reflected the bleakness and crushing of emotion in underclass life even more than it was about classic rapper's self-aggrandisement. His erstwhile sparring partner Wiley's productions, too – the most influential in grime by quite some distance – were bipolar, flicking from rambunctious aggression to frozen, empty stasis in a second; the latter quality reflected in his instrumentals' titles - “Ice Rink”, “Eskimo”, “Avalanche”.

I recall one piece by the great music blogger and journalist Martin Clark, which visited Wiley's Roll Deep Entourage in the Limehouse estate where they lived, and made explicit connections between the brutal contrasts there – between the poverty of the estates and the glaring symbols of wealth like Canary Wharf that towered over them – and the cold ambition in their sound and lyrics.

But grime still remained of a part with the UK's history of rave music, energetic and funny as well as cold and strange. Much nastier still has been the development of “road rap” or UK gangsta hip hop over the past few years – this sound is rarely upbeat or cathartic in any way, but simply psychopathic in its delivery and content. It is also often harrowingly brilliant.

The producer El-B, who engineered many rap tracks, described the scene to me thus in 2009: “It's not grime, it's hip hop. It's rap. BUT it's not getting touched with a bargepole by the industry because it commands - not even influences, but commands - the kids to go and do bad things, it's real bad, man. The rappers say "I'm just reflecting the neighbourhood" or "I'm reflecting my life" or "I'm just telling you what I see, what I've been through" - which is cool, but the kids love it, and it tells you that life is about selling cocaine, and about having your gun to shoot it not to have it in the cabinet, it's about being about your tings and shooting it, if you've got it shoot it off and do that [flicks Vs] to the police.”

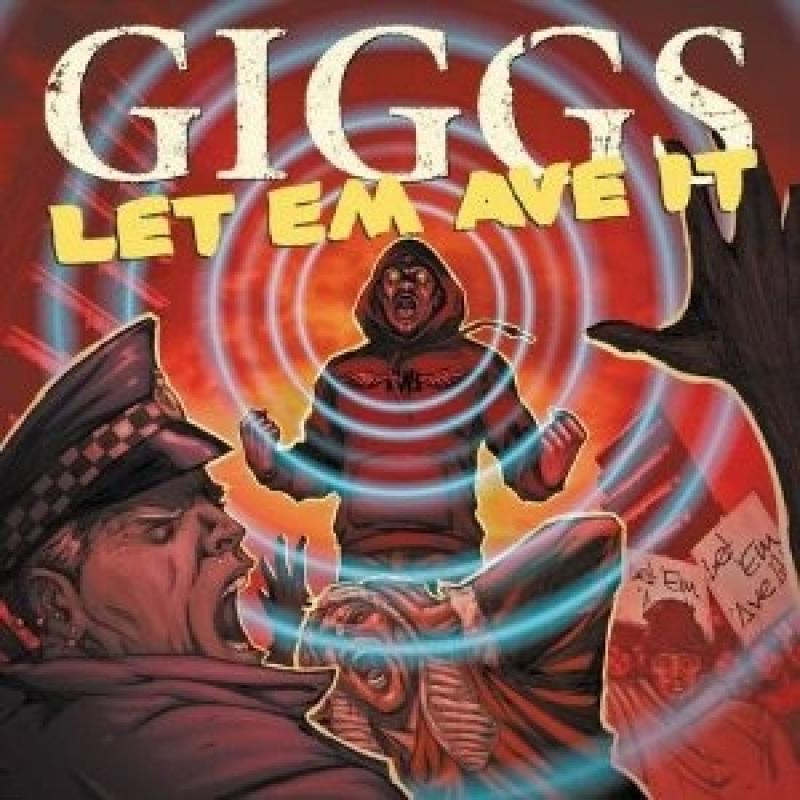

In fact the figurehead for road rap, Peckham's Giggs, has since been signed to a large label and enjoyed some success, but the bulk of the tracks are released on self-pressed CDs, given away online or simply posted on YouTube. A few of the leading artists, like Blade Brown, have a smart if grim wit and insight into the life of drug dealing, but the majority are the “youngers”, teenagers who will film “hood videos” on camera phones consisting of litanies of threats, byzantine detailing of gang rivalries and acquisitive nihilism.

For me, the summing up of this scene's apolitical grimness came in Blade Brown's line from one online freestyle: “I don't rap about black power/ I'd rather hear a Mac shower”, that is, he is not interested in raised consciousness or social change, he would rather hear the sound of the shower of bullets from a Mac 10 machine pistol for the sheer love of power and violence.

Watch Blade Brown's performance for SBTV

That is the mentality behind what we have seen these past few days, and it is also a stark warning of worse if Britain doesn't deal with its problems and fast. I'm ambivalent as to whether music really influences people: as El-B says, these tracks certainly try to command the living of a lifestyle, and the participation of gangs in making online rap videos shows it is a part and parcel of that lifestyle. But no record can create the horrific withering of the human soul – the cold, dead-eyed attitude to violence – that comes with the ubiquity of drugs, a failing of institutions, and from the exclusion which, as Camila Batmanghelidjh writes in today's Independent, “grows when a child is dragged by their mother to social services screaming for help and security guards remove both; or in the shiny academies which, quietly, rid themselves of the most disturbed kids...”

Clearly, nobody knows what is going to unfold in coming days, weeks, months, years, and there are no easy solutions at all. But perhaps our policy makers - and we in the media - would be less at a loss if we had spent just a little less time trying to curry favour with smiling pop stars for their PR value, and more time taking in and trying to genuinely understand the bleakness of early Wiley and Dizzee, or latterly the fury of Tempa T and the shark-eyed sardonicisms of Blade Brown. So many of the voices out there on CDs and online are teenagers - attention-seeking kids - and maybe, just maybe, if we gave them the attention they craved, we might have realised how bad the malaise in our cities was growing.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Emily A. Sprague realises a Japanese dream on 'Cloud Time'

A set of live improvisations that drift in and out of real beauty

Emily A. Sprague realises a Japanese dream on 'Cloud Time'

A set of live improvisations that drift in and out of real beauty

Comments

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...