Arshile Gorky: A Retrospective, Tate Modern | reviews, news & interviews

Arshile Gorky: A Retrospective, Tate Modern

Arshile Gorky: A Retrospective, Tate Modern

Major artist whose story has dominated his art

Arshile Gorky found it almost impossible to finish a painting. Something would always call him back. So he would go back and would add and retouch and tinker around over several years - sometimes over the course of a decade or two. “When something is finished,” he once said, “that means it’s dead, doesn’t it? I never finish a painting, I just stop working on it for a while. The thing to do is... never finish a painting.”

His early paintings, his figurative still-lifes, particularly - not the late, softly fluid, lyrical abstractions that would profoundly influence the course of American art - are often so densely built up, so airtight with paint, that they’ve more or less had the life choked out of them; in the course of trying to keep them alive, they have in fact become dead things.

Perhaps all you can really say, is poor, tragic Gorky. His early life is full of death, so it’s no wonder he had trouble letting go. Death had, after all, been the defining experience of his life, and one feels that of all the Hollywood artist biopics to ever hit the screen, Gorky’s life would probably make the most compelling (and after three biographies written over the course of the last decade, we duly await studio interest).

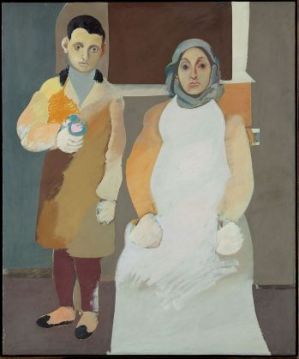

These are the stark facts of Gorky‘s life, and their memories were to haunt his best work. Born in around 1904 (the exact year remains uncertain) in Khorkum, the Armenian province of Van, Gorky lives with his mother, father and sister till about the age of five. In 1908 his father abandons the family home and leaves for America. He settles in Rhode Island, while the family are left to suffer acute hardship back home. In 1912, Gorky's mother goes to the expense of having her portrait photo taken along with her only son. She will send this photograph to her husband to remind him that he still has a family to support (it is this photograph that Gorky later discovers in his father’s drawer and he uses it as the source of his most enduring and powerful painting.

In 1915, fleeing on foot to Yerevan in Russian Armenia, the family survive the Turkish Armenian massacre, only for his mother to eventually die of starvation in her son's arms. In 1920 Gorky boards a boat to America, and begins the business of reinvention: he changes his name from Vosanig Adoian and claims that he is either the cousin or the nephew of Maxim Gorky. He is unaware that the name of the Russian dramatist is itself a pseudonym.

Gorky is an artist who bridged the gap between European Surrealism and American Abstract Expressionism, and yet he largely fell through that gap. His life has, in fact, often overshadowed the work, yet the work itself has always been overshadowed by the two big movements that he appears at the ends and beginnings of. His early paintings aren’t actually much to speak off, though.

Apart from those dense, overworked canvases that predate the rapid awakening that follows his discovery of Surrealism and its darkly playful, biomorphic forms, there are the many well-executed pastiche paintings, the ones where Gorky skilfully "does" Cezanne and Picasso. In Tate Modern’s otherwise fascinating survey, perhaps there are just too many of these on display - though through them, we do gain a fuller understanding of the distinct stages of Gorky's development (he began weighted with clodhopper boots, you might say, but then he began to fly).

His later paintings, those painted at the height of his creativity in the 1940s, are something else altogether. With their nascent, slippery forms they often allude, enigmatically, to memories of his Armenian past, and, more specifically, to memories of his mother. “Her stories and the embroidery on her apron get confused in my mind,” he once wrote. “All my life her stories and her embroidery keep unravelling pictures in my mind.”

The spidery calligraphic lines, the half-developed forms, the translucent washes of colours, all appear to capture something - a bird, a plough, a pattern on a dress; but the dissolving forms continually configure and unravel before our eyes. We also find the suggestively menacing forms which prefigure Willem de Kooning, an artist Gorky would profoundly influence. If you look closely at One Year the Milkweed (main picture), those blood-red dashes accompanied by thinly dripping lines of paint will almost certainly make you think of those disturbing grins on de Kooning's Women.

But a more explicit tribute to his mother can be found in two similar canvases, both entitled The Artist and his Mother. One was executed, on and off, over a period of 10 years (1926-1936, pictured right), the other over a period of a decade and a half (1926-1942) - two paintings he really couldn’t let go of. It is undoubtedly the one owned by the Whitney Museum, the "quicker" version, that is the greater. Staring out of grave, mask-like faces, the boy simply looks unbearably sad and rather lost, while the mother's face suggests both stoicism and accusation. Her hands are made into useless, dough-like fists, while young Vosanig proffers, in his own fist, a flower. The gesture is both pathetic and touching. This painting is hung so that it is visible through a long vista of galleries, so that it is encountered as soon as we step into the exhibition. In this sweeping retrospective, it is a painting that deserves that honour.

But a more explicit tribute to his mother can be found in two similar canvases, both entitled The Artist and his Mother. One was executed, on and off, over a period of 10 years (1926-1936, pictured right), the other over a period of a decade and a half (1926-1942) - two paintings he really couldn’t let go of. It is undoubtedly the one owned by the Whitney Museum, the "quicker" version, that is the greater. Staring out of grave, mask-like faces, the boy simply looks unbearably sad and rather lost, while the mother's face suggests both stoicism and accusation. Her hands are made into useless, dough-like fists, while young Vosanig proffers, in his own fist, a flower. The gesture is both pathetic and touching. This painting is hung so that it is visible through a long vista of galleries, so that it is encountered as soon as we step into the exhibition. In this sweeping retrospective, it is a painting that deserves that honour.

And as for how Gorky's compelling story ends? Unfortunately, not well. After suffering, in alarmingly quick succession, a series of misfortunes - a fire in his Connecticut studio which destroyed years of work, rectal cancer, after which he had to have a colostomy, a car crash that broke his neck, the break-up of his marriage over his wife's affair with a close artist friend - Gorky hanged himself in 1948. Fortunately for us, with or without the back-story, the work survives.

- See Arshile Gorky: A Retrospective at Tate Modern until 3 May.

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Comments

...