National Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

National Gallery

National Gallery

Frederick Wiseman's latest documentary is a great work of art

The octogenarian Frederick Wiseman is a cult documentary film maker, with his own idiosyncratic and recognisable idiom. He has both vast experience and extraordinary independence. Characteristically, he makes long, prize-winning, fly-on-the-wall inside-the-institution films: reportorial, non-judgemental, loosely narrative, and wide in subject – from a hospital for the criminally insane, to a high school, the largest university in California (Berkeley), or the Paris Opera Ballet.

The newest, aired (and winning prizes) at international festivals, is an extraordinary view of the National Gallery, really as you have never seen it before. The film is distilled from three months of filming, 12 hours a day, in 2012, clustered in part around several major exhibitions – Turner In the Light of Claude, Leonardo, and Titian Metamorphoses among others. From his 170 hours of rushes, Wiseman further refined and defined down in over a year of editing to a film of just under three hours.

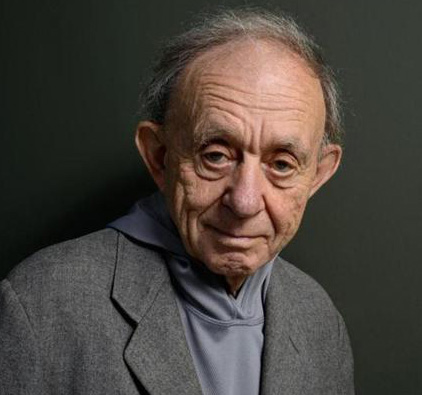

Wiseman (pictured right) is director, editor and sound recordist, his very small team including his regular John Davey as cameraman. He finds the film in the editing. What he is passionately interested in is human behaviour, and the institution he is observing acts as the container, with its own idiosyncratic rules, regulations and rituals. Visitors and staff are the seemingly wholly unwitting actors in the various human dramas that unfold, but are here accompanied by a continual array of masterpieces in paint, each as individual as the living people under the filmmaker's scrutiny. There is no spoken narrative, no voice over, no explanation, no background music. We have to infer who anybody might be, from curator to director, conservator to benefactor, guide to executive. We eavesdrop on meetings, discussing budget shortfalls or mission statements. We even watch a programme being made within the film, as the BBC interrogates a pair of curators about the Leonardo exhibition.

Wiseman (pictured right) is director, editor and sound recordist, his very small team including his regular John Davey as cameraman. He finds the film in the editing. What he is passionately interested in is human behaviour, and the institution he is observing acts as the container, with its own idiosyncratic rules, regulations and rituals. Visitors and staff are the seemingly wholly unwitting actors in the various human dramas that unfold, but are here accompanied by a continual array of masterpieces in paint, each as individual as the living people under the filmmaker's scrutiny. There is no spoken narrative, no voice over, no explanation, no background music. We have to infer who anybody might be, from curator to director, conservator to benefactor, guide to executive. We eavesdrop on meetings, discussing budget shortfalls or mission statements. We even watch a programme being made within the film, as the BBC interrogates a pair of curators about the Leonardo exhibition.

We go to two life classes within the National Gallery, one drawing a young naked woman, one with a young naked man; we watch another class and gradually realise that each pair of middle-aged students consists of a visually impaired person accompanied by a sighted companion who is guiding their hands over a three-dimensional reproduction of a Pissarro view of Montmartre – ironically a scene of night-time Paris.

And we see lots and lots and lots of paintings, perhaps as many as 250 out of – say – the 2400 in the collection, one of the finest, in terms of quality, in the world. And we hear about them too, attending talks from the guides as well as the curators, and even more, from the mysterious, alchemical department of conservation and restoration.

We open to sounds of traffic and a view of the vast horizontal gallery that dominates the northern boundary of Trafalgar Square, and then we enter the silent and empty galleries; a low purring sound turns out to be the harbinger of the floor polisher and its attendant gliding into view. Soon we are part of the audience listening to guides in front of specific pictures; but we also wander the galleries, with no titles to read, just the pictures to look at.

There are sequences of details too, and almost endless portraits of saints and grandees, of naked nymphs and ferocious gods, many taken close up without even their frames in view. They gaze at us as we gaze at them. What is striking, indeed almost overwhelming, is not only the extraordinary range and spectrum of the 21st century visitors – babies and tourists, adolescent students and earnest middle-aged spectators, looking intently or wandering apparently aimlessly. Some are asleep on the benches, others are kissing in a corner. Many stroll through not even looking, somehow content on a pilgrimage just to be in the presence of the bones of the saints, worshipping in a casual way in the secular cathedral a museum can so easily become.

There are sequences of details too, and almost endless portraits of saints and grandees, of naked nymphs and ferocious gods, many taken close up without even their frames in view. They gaze at us as we gaze at them. What is striking, indeed almost overwhelming, is not only the extraordinary range and spectrum of the 21st century visitors – babies and tourists, adolescent students and earnest middle-aged spectators, looking intently or wandering apparently aimlessly. Some are asleep on the benches, others are kissing in a corner. Many stroll through not even looking, somehow content on a pilgrimage just to be in the presence of the bones of the saints, worshipping in a casual way in the secular cathedral a museum can so easily become.

Above all we are reminded of the strangeness of it all: these relics, mostly priceless (that is, worth an awful lot of money) are very far in terms of time and place from their original context. Nothing of course was painted specifically to be shown in Trafalgar Square, so nothing here is seen in its original setting and thus is also remote from its original meaning. The paintings are as strange as we are. As the camera alights first on a lecture in front of a specific painting to disparate groups – mothers and toddlers, black schoolchildren (with a PC mention of the fortunes made from slavery that part funded the founding of the National Gallery itself – no white adult group was treated to this insight), the bewildered tourist and the dedicated regular – we are reminded all the time how art history is a guessing game, with clues to be followed up as best we can.

In between set pieces, such as the director resisting his populist staff who are quite happy for Sports Direct to project signage on the actual building to mark the end of their marathon, we are among the shifting crowds of visitors, and hear their murmurings. We pause with professional scholars too, scrutinising particular works; and one nighttime we are outside with the police witnessing Greenpeace unfurling a protest banner about Shell drilling in the Arctic, Shell being a sponsor of the Gallery.

The most hypnotically fascinating group are the individuals who see to the physical care of the art: framemakers, restorers, conservators. The inadvertent star (no one at the Gallery either saw the film in progress nor having given permission had any input into what it could portray) is a restorer whose name we learn is Larry. He shows visitors the hidden painting behind a Rembrandt equestrian portrait, and discusses the processes of deciding restoration projects and techniques. A scholarly curator named Dawson tells us that in the 21st century all restoration is reversible, taking place on top of the painting’s varnish. Both these characters, threaded through the episodes, have North American accents, reminding us that it is not only the paintings and the visitors that are international.

The most hypnotically fascinating group are the individuals who see to the physical care of the art: framemakers, restorers, conservators. The inadvertent star (no one at the Gallery either saw the film in progress nor having given permission had any input into what it could portray) is a restorer whose name we learn is Larry. He shows visitors the hidden painting behind a Rembrandt equestrian portrait, and discusses the processes of deciding restoration projects and techniques. A scholarly curator named Dawson tells us that in the 21st century all restoration is reversible, taking place on top of the painting’s varnish. Both these characters, threaded through the episodes, have North American accents, reminding us that it is not only the paintings and the visitors that are international.

Throughout, it is the paintings themselves that are the most surprising element. We look at Rubens’s Samson and Delilah twice, once with a docent who tells the story, with persuasive imagination, and once with a guide concerned with how the light falls in the painting and how it might have been originally hung. We are treated continually to the painted faces and writhing muscular bodies of gods, nymphs, and martyrs.

The final sequence is the most surreal. In a darkened gallery, a trio of Titian paintings softly glowing, two Royal Opera House dancers perform a pas de deux to music by Byrd; and as the dancers depart, a sequence of eight Rembrandt portraits – young and old, men and women, real and legendary, ending with a self portrait – gaze with sceptical disbelief, sly humour, or resignation, to all that they have seen of the life of the Gallery in which they reside.

Overleaf: watch the trailer for National Gallery

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

Hello, What a great review!

Apologies, many thanks, now