Hofesh Shechter, Political Mother: The Choreographer's Cut, Sadler's Wells | reviews, news & interviews

Hofesh Shechter, Political Mother: The Choreographer's Cut, Sadler's Wells

Hofesh Shechter, Political Mother: The Choreographer's Cut, Sadler's Wells

A ferocious wall of sound - and sight

Only three years ago, Hofesh Shechter, the Israeli-born, London-based choreographer, made the leap into the big leagues, almost overnight, with his Uprising/In Your Rooms double bill. The following year he produced a "Choreographer’s Cut", a bulked-up version in the Roundhouse, part dance, part gig. 2010’s Political Mother was received with rapture, so what next?

The piece starts with a section of Verdi’s Requiem, string players appearing suspended in the dark on a transparent balcony, each seemingly isolated. Then, a static burst cuts them off, and thrash, above them appear guitarists and percussionists; thrash again, and more percussionists below – Phil Spector never imagined a wall of sound like this. All this has taken place behind an empty stage; now a lone man, a Japanese warrior, unsheathes his sword and kneels, slowly, ritually, committing seppuku. Another blackout – which is typical of Shechter’s cinematic-like love of blackouts and cross-cutting. Two men enter a triangle of light to perform what seems like a folkdance, but a folkdance on acid, febrile, stuttering, shimmering, as though electricity is coursing through their bodies. A demagogue appears above, ranting incomprehensibly in front of lighting that mimics Leni Riefenstahl's films.

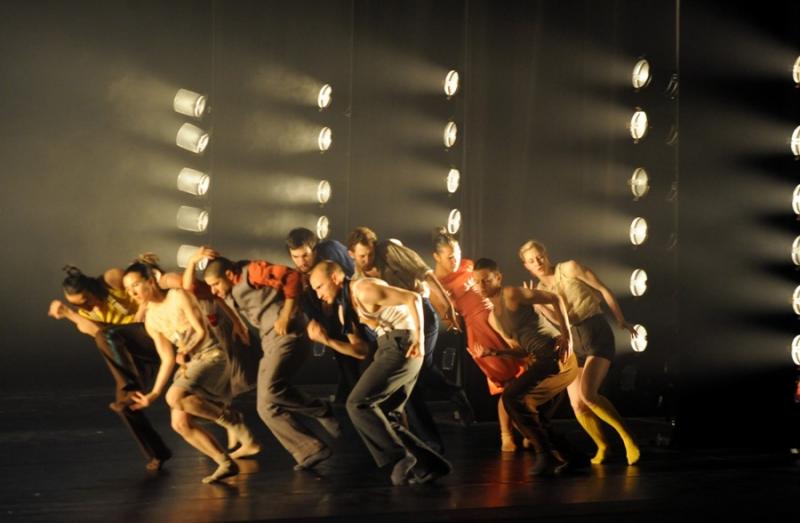

And now we are away. Shechter’s subject is the vagaries of power, the shifting alliances, moving swiftly between subjection and oppression, victims and perpetrators. It is never clear entirely which is which, and that is of course his point. He uses his core folk-inflected vocabulary to sketch a picture of the people and their need for freedom, but in an eye-blink he then transforms their arms raised in joy to the raised hands of the prisoner; similarly the folk-stamp switches from rustic vigour to that of the prisoner pounding the exercise yard.

And now we are away. Shechter’s subject is the vagaries of power, the shifting alliances, moving swiftly between subjection and oppression, victims and perpetrators. It is never clear entirely which is which, and that is of course his point. He uses his core folk-inflected vocabulary to sketch a picture of the people and their need for freedom, but in an eye-blink he then transforms their arms raised in joy to the raised hands of the prisoner; similarly the folk-stamp switches from rustic vigour to that of the prisoner pounding the exercise yard.

The only other contemporary choreographer who relies on folkdance as much as Shechter is Mark Morris, and the differences between the two are illuminating. Morris loves folkdance for its formal qualities, its geometric parsing of space: if you will, its classicism. Shechter is interested in its emotional content, perhaps a more obvious route to take, but one no less potent for that. And both men appreciate its tribal rhythms, whether it is Morris’s masterpiece, Grand Duo, or Shechter’s prisoners finding the light.

Shechter limits his dancers to a small palette of movement – the raised or flailing arms, the skipping step, the hitched knees; often they all move in circular shapes, marking a regular pattern. Shechter is one of the few contemporary choreographers who has a natural flair and love of massed movement, in all its glorious complexity. These patterns he builds become elemental, tightly pounded out and meshed to his own music, and, even more, luminously displayed in Lee Curran’s brilliantly theatrical lighting design – a tour de force which builds a world which Shechter can then people. Indeed, one of the best things about Political Mother is precisely the tight integration between these two – take away either element and it would all fall apart.

While the piece, the choreographer and the creative team are all admirable, it might be wished that this Choreographer’s Cut had developed a little further since the piece’s first outing. The start is slow: Shechter’s method of cumulatively building out of small episodes means it takes nearly a quarter of an hour before we are underway. While this method does, ultimately, reap rewards, it wouldn’t hurt to get there a little faster. Occasionally, too, the skittery, jittery dance elements become etiolated, slightly effete, compared to the thrusting nature of most of the choreography: one trio resembled Moe, Larry and Curly attempting folkdance – not a good look. The ending, too, still doesn’t work – after the prisoners see the light, the cryptic message “Where there is pressure, there is folkdance” illuminates the stage, the pulsing beat uncoils the dancers into a final folkdance enfilade – and then the lights go out, and we get another puzzling five minutes of dance, undoing all that has been achieved.

While the piece, the choreographer and the creative team are all admirable, it might be wished that this Choreographer’s Cut had developed a little further since the piece’s first outing. The start is slow: Shechter’s method of cumulatively building out of small episodes means it takes nearly a quarter of an hour before we are underway. While this method does, ultimately, reap rewards, it wouldn’t hurt to get there a little faster. Occasionally, too, the skittery, jittery dance elements become etiolated, slightly effete, compared to the thrusting nature of most of the choreography: one trio resembled Moe, Larry and Curly attempting folkdance – not a good look. The ending, too, still doesn’t work – after the prisoners see the light, the cryptic message “Where there is pressure, there is folkdance” illuminates the stage, the pulsing beat uncoils the dancers into a final folkdance enfilade – and then the lights go out, and we get another puzzling five minutes of dance, undoing all that has been achieved.

But this is not to deny the sheer visceral thrill of Political Mother, or the enormous artistry that has gone into creating it.

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Comments

I was tremendously

Absolutely! Really surprised