Einstein on the Beach, Barbican Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

Einstein on the Beach, Barbican Theatre

Einstein on the Beach, Barbican Theatre

Technical cock ups can't obscure the genius of this Glass-Wilson-Childs collaboration

Einstein on the Beach was meant to be one of the jewels in the crown for the Cultural Olympiad. The celebrated 1970s collaboration between Philip Glass, Robert Wilson and Lucinda Childs - which Susan Sontag claimed to be one of the greatest theatrical experiences of the 20th century - was receiving its UK premiere at the Barbican Theatre last night, thirty-six years after it was first created. And what we got was a technical shambles.

Pretty much everything that could go wrong technically did go wrong. Lighting cues were botched. Drop cloths rose prematurely. Stage hands wandered on from the wings in error. An enormous crane got stuck in the fly system and swung precariously above the performers. They took a break to fix that one. Wilson took the stage to apologise and announce that the flying elements would have to be cut from the penultimate scene. They restarted without half the audience. It would have been embarrasing from an amateur dramatics society let alone the Barbican.

There's more dramatic tension in the first 10 minutes of Einstein than in most productions in a whole Royal Opera season

The work is complicated, the Barbican Theatre will say in defence. But it wasn't complicated for Montpellier. How is it that a French provincial theatre, where the work was premiered a couple of months ago - and which I saw twice - can completely nail a work such as this, with only one rehearsal, and a supposedly world class venue can foul up so royally? Was there not enough rehearsal time? Was there any rehearsal time at all? Was the work ever really suited to the Barbican? The action seemed squeezed on their tiny stage and minuscule pit. And if they couldn't deal with the demands of the production, should they ever have taken the project on?

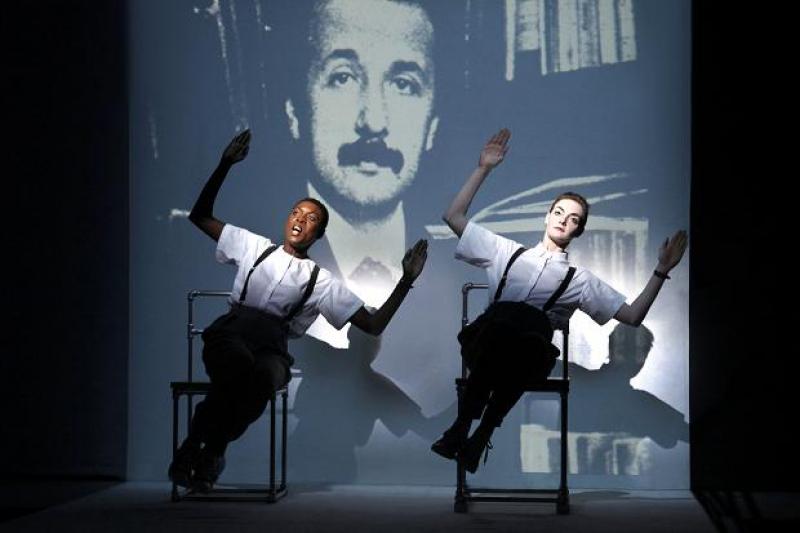

There was at least one up side to all this. It meant one could explode one of the most oft-repeated myths about Einstein on the Beach: that the work is minimalist. There may be no conventional plot, no conventional meaning, no real drama. The music might unfold at such a glacial pace that it seems not to unfold at all. But musically, theatrically, gesturally, verbally, vocally, visually, and in its terpsichorean and technical elements, Einstein is Baroque. It's bursting at the seams with goings on. Trains and cranes and courts and lovers and guns and Einstein playing the violin (the superb Antoine Silverman) and dancers. Luckily, this fecundity of imagination and activity had the most brilliant cast to make visual sense of it all.

And it is a visual sense you're after, not a literary sense. Abstract gestural beauty is the point of Wilson's staging. Look for meaningful drama and you will be disappointed. But look for tableaux of unforgettable freshness and you will be handsomely rewarded. The best scenes are those in which the least happens. A light box rendered as a bright white bar slowly lifts and rises into the heavens. A choir of jurors take lunch. A woman gestures furiously in the top window of a luminous brick building. Singers and dancers file out onto the stage and stand. Yep, just stand. Heels cocked. They catch sight of the woman and leave. In Wilson's hands, all of life's basics - sitting, looking, standing, jumping, eating - are refashioned in such a way as to make them completely mesmerising. I could have watched the bended elbows of Kate Moran (one of two slightly creepy, anonymous and nonsense-spouting comperes) all day.

The audience began to hum and headbang. It was hard not to

Einstein also has one of the great openings. There's more dramatic tension in the first ten minutes of the work - as singers with unnerving smiles file out and scan the audience - than in most productions in a whole Royal Opera House season. Comparing Einstein to other operas, however, is unfair. There is a link to Virgil Thomson's Four Saints - the only other opera before Einstein to set aside meaning and plot - but Einstein is far closer to performance art than opera in its visually literacy and its exploratory feel.

There is also hardly anything that resembles the kind of singing you might see at an opera - even a contemporary one. There is one duet but it is hardly conventional - repeated arpeggios sung to solfege. There are also some ravishing chorales with words replaced by numbers. But mostly we get fiendishly complex choral atmospherics and breathtaking ululation. The latter - fast paced, constantly shifting in rhythm and lightly dissonant - accompanies one of the most thrilling elements of the night: Childs's two twenty-minute dances.

With no stage work for the Barbican to fuck up, these set pieces, in which the whole arena is bathed in a pearlescent light, saw the extraordinary Childs dance company electrify the space. The dance starts small, with simple steps, and builds and builds in the manner of Glass's music, through addition and subtraction, all of it in virtuosic sync with the sound of Glass's waves of rich, throbbing music. Evoking the power of a physical force field, the result is kinetic and overwhelming.

Minimalist music doesn't get much more lush or surprising

All this intricate and varied stagework is underpinned by one of Glass's finest scores. It marks the end of his first and most experimental phase - before he entered neo-Romanticism - and amalgamates not just all his compositional techniques up to that point but virtually every Minimalist language of the 60s and early 70s: Harold Budd's electronic fantasias, La Monte Young's drones, the free jazz of Terrys Riley and Jennings, the marimba colour of Reich and his own compositional innovations.

It incorporates these languages and scatters them across a generous wealth of instruments among the Philip Glass Ensemble. We get tumescent jazz saxophone riffs (from the frenzied David Crowell), violin solos and neo-Baroque organ fantasias (from conductor Michael Riesman). Minimalist music doesn't get much more lush or surprising. Or catchy. Like in Montpellier, the audience began to hum and headbang. It was hard not to.

Many people look upon the five-hour Einstein as an endurance test. But this couldn't be further from the reality of experiencing it. This is an opera that is supremely generous: generous in how it allows you to think, what it allows you to do, what it offers. It's the very opposite of an endurance test. People can come and go. People can snooze. There is in fact enough of a skeleton of a plot - we travel in cryptic mode from childhood to adult love to annihilation - to gently entertain those craving narrative. And the work is so steeped in the context it was written - 70s America - referencing women's lib, Patti Hearst's killing spree, civil rights and the Cold War, that there is even the possibility (for those who care to do the deciphering) to elicit meaning from it all.

The technical bungling can't obscure the fact that Einstein is a masterpiece and catching it in whatever state is worth every penny of the £100 plus price tag. Einsteins only come once in a blue moon. See it while you can.

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

Have just seen Einstein on

Have just returned from

Saturday nights show was

Saturday performance -

these are the days my

I'm so glad to hear Friday's

I saw it last night. The