Léon Spilliaert, Royal Academy review - a maudlin exploration of solitude | reviews, news & interviews

Léon Spilliaert, Royal Academy review - a maudlin exploration of solitude

Léon Spilliaert, Royal Academy review - a maudlin exploration of solitude

The world seen through the eyes of melancholy

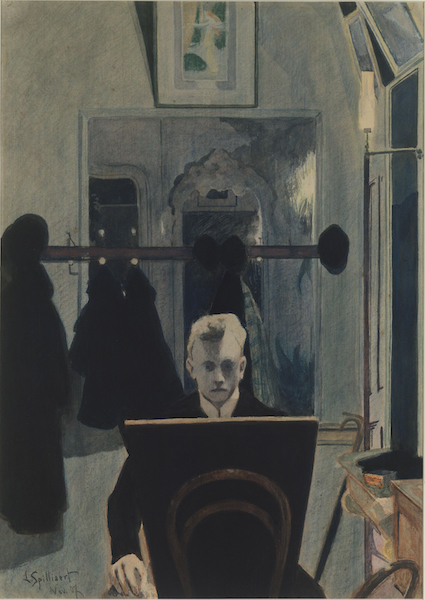

What a spooky exhibition! Léon Spilliaert suffered from crippling insomnia and often spent the nocturnal hours in the conservatory of his parents’ house in Ostend drawing his haggard features (pictured below right: Self-portrait, 1907).

The artist also roamed the deserted streets and recorded them in sombre pictures whose unusual viewpoints and exaggerated perspectives create a filmic sense of dread. With towering walls reflected in wet tarmac, Hofstraat, Ostend from 1908 becomes a bleak canyon illuminated by a single, distant light. The same dramatic perspective channels one’s eye down Ostend’s empty pier towards the lighthouse at the end and the waves beyond. Spilliaert rented a studio overlooking the busy port, but instead of recording this hive of activity, he preferred to capture empty, windswept beaches and looming clouds.

Spilliaert married in 1917 and had a child, but only two drawings of his wife, Rachel, are on show. He was determined, it seems, to focus on the darker side of life. Misery, 1909 comprises a black garment hanging from a rope in a room empty save for a wooden trunk. Love, 1901 is an ink drawing of a scrawny little man clinging to a tall woman and gazing up at her with a mixture of devotion and despair. The couple are framed in a hoop of light that bleeds a sorrowful fringe of black ink from its lower edge.

Not surprisingly, Spilliaert was drawn to the dark fantasies of authors like Edgar Allan Poe and in 1902 he began illustrating the work of writers such as Maurice Maeterlinck and the Symbolist poet Emile Verhaeren, who shared his brooding intensity. All in all, this feels like a life lived in front of the mirror and the drawing board, rehearsing melancholy as well as experiencing its clutches.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Ed Atkins, Tate Britain review - hiding behind computer generated doppelgängers

Emotions too raw to explore

Ed Atkins, Tate Britain review - hiding behind computer generated doppelgängers

Emotions too raw to explore

Echoes: Stone Circles, Community and Heritage, Stonehenge Visitor Centre review - young photographers explore ancient resonances

The ancient monument opens its first exhibition of new photography

Echoes: Stone Circles, Community and Heritage, Stonehenge Visitor Centre review - young photographers explore ancient resonances

The ancient monument opens its first exhibition of new photography

Hylozoic/Desires: Salt Cosmologies, Somerset House and The Hedge of Halomancy, Tate Britain review - the power of white powder

A strong message diluted by space and time

Hylozoic/Desires: Salt Cosmologies, Somerset House and The Hedge of Halomancy, Tate Britain review - the power of white powder

A strong message diluted by space and time

Mickalene Thomas, All About Love, Hayward Gallery review - all that glitters

The shock of the glue: rhinestones to the ready

Mickalene Thomas, All About Love, Hayward Gallery review - all that glitters

The shock of the glue: rhinestones to the ready

Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland talks about the dramatic changes in the Arctic

An ominous shift has come with dark patches appearing on the Greenland ice sheet

Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland talks about the dramatic changes in the Arctic

An ominous shift has come with dark patches appearing on the Greenland ice sheet

Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker, Whitechapel Gallery review - absence made powerfully present

Illness as a drive to creativity

Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker, Whitechapel Gallery review - absence made powerfully present

Illness as a drive to creativity

Noah Davis, Barbican review - the ordinary made strangely compelling

A voice from the margins

Noah Davis, Barbican review - the ordinary made strangely compelling

A voice from the margins

Best of 2024: Visual Arts

A great year for women artists

Best of 2024: Visual Arts

A great year for women artists

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

ARK: United States V by Laurie Anderson, Aviva Studios, Manchester review - a vessel for the thoughts and imaginings of a lifetime

Despite anticipating disaster, this mesmerising voyage is full of hope

ARK: United States V by Laurie Anderson, Aviva Studios, Manchester review - a vessel for the thoughts and imaginings of a lifetime

Despite anticipating disaster, this mesmerising voyage is full of hope

Comments

It seems your beef is with