The Love for Three Oranges, Grange Park Opera | reviews, news & interviews

The Love for Three Oranges, Grange Park Opera

The Love for Three Oranges, Grange Park Opera

Prokofiev's fairytale is bizarrely sung in Hampshire in neither Russian nor English

“Art and love, these have been my life,” sings Tosca in Puccini’s opera. “Music or words first?” the Countess worries in Strauss’s Capriccio. Now in the third of Grange Park’s operas this summer we have the warring advocates of tragedy, comedy, melodrama and farce in Prokofiev’s Love for Three Oranges. Could it be guilt at its own idle detachment that draws country-house opera into the agony of self-reflective theatre? Well, Tosca is barely self-reflective – an excuse for a big aria and an off-stage cantata. But Prokofiev’s Oranges – like that other, and better, Strauss concoction, Ariadne auf Naxos – derives both humour and instruction from our lurking fear that all these stage passions, triumphs and disasters are mere trickery and greasepaint. And it does so in music that vibrates with energy and sardonic wit from first bar to last, music strictly devoid of serious agony.

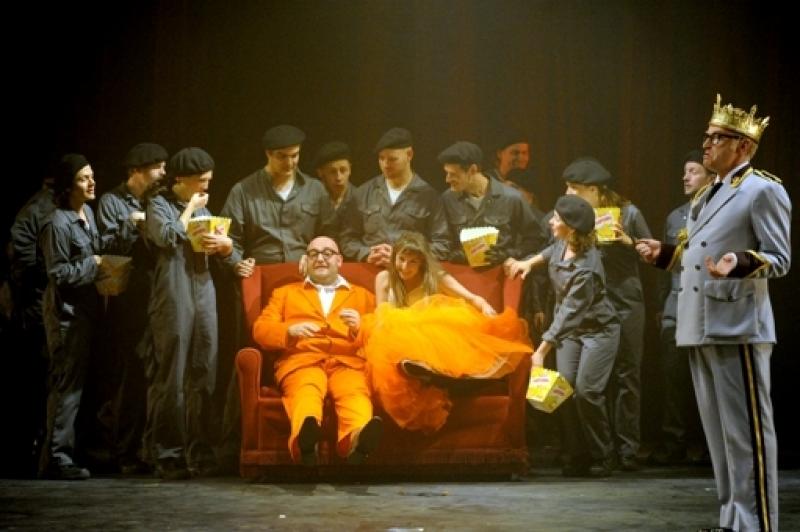

The opera, like its source Gozzi play, is a spoof fairytale. A prince dying of melancholia finds nothing amusing except the sight of the evil fairy Fata Morgana flat on her back, for which indiscretion she condemns him to fall in love with three oranges. The oranges, when found, turn out to house three beautiful princesses, two of whom at once die of thirst, while the third is saved only by a bucket of water provided by the so-called Eccentrics in the audience (roughly, the untroubled theatre-lovers): and so on. The nuances come thick and fast. Yet, as in any good pantomime, narrative logic is never quite sacrificed to magical intervention; it’s merely speeded up by it. And speed is a strong feature of David Fielding’s production at the Grange: speed in the sense of stage choreography, and in the sense of quick-witted integration of hybrid elements.

Fielding does his own designs, and their eclecticism fits the spirit of the score exactly; in fact a lot of the visual jokes are already in the stage directions. Some directorial clichés, like the inevitable cloned bearded doctors with stethoscopes, are after all justified by the story. Other modernisms, the princesses’ giant orange-juice cartons (“two for the price of three” – why not three for the price of two, by the way?), or the Dr Who phone box that whisks the Prince away to the wicked Creonta’s kitchen, are bang on the Prokofiev nail, if beyond his ken. The magic flashes and fizzes in the best pantomime tradition, and the fake audience groups are brilliantly organised, as well as sparklingly sung, on and off stage, not least in the set pieces – like the famous march and scherzo – which ultimately suggest Prokofiev was more at home in ballet than opera, for all the deftness of this particular specimen.

Musically there is a strong performance waiting in the wings here. The cast is too big to itemise, but Clive Bayley’s King of Clubs, Jeffrey Lloyd-Robert’s Prince, and Wynne Evans’s Truffaldino shouldn’t go unmentioned. Of three very nubile princesses, the survivor, Rosie Bell, hits off the delicious absurdity of the situation to a tee. Vuyani Mlinde’s top-hatted magician Tchelio and Rebecca Cooper’s tall, sexy Fata Morgana are a perfectly matched pair – an illusionist and his assistant gone to the bad. All clever, well-observed, well-sung portraits.

Leo Hussain, a young conductor I haven’t encountered before, is well on top of the score, without quite holding the lid on its volume, which sometimes makes life hard for his singers. But what’s hardest of all for them is the inexplicable decision to sing the opera in (rather bad) French, a language that has no relevance to either the work or its audience. Sure, it was premiered in French in Chicago; but that was for local reasons. This is a Russian opera, a comedy to boot, and the only sane language to sing it in in England is English. The audience might then manage to laugh in the right places, and much, much more often; because as well as being musically a treasure, The Love for Three Oranges is, or should be, very, very funny.

“Art and love, these have been my life,” sings Tosca in Puccini’s opera. “Music or words first?” the Countess worries in Strauss’s Capriccio. Now in the third of Grange Park’s operas this summer we have the warring advocates of tragedy, comedy, melodrama and farce in Prokofiev’s Love for Three Oranges. Could it be guilt at its own idle detachment that draws country-house opera into the agony of self-reflective theatre? Well, Tosca is barely self-reflective – an excuse for a big aria and an off-stage cantata. But Prokofiev’s Oranges – like that other, and better, Strauss concoction, Ariadne auf Naxos – derives both humour and instruction from our lurking fear that all these stage passions, triumphs and disasters are mere trickery and greasepaint. And it does so in music that vibrates with energy and sardonic wit from first bar to last, music strictly devoid of serious agony.

The opera, like its source Gozzi play, is a spoof fairytale. A prince dying of melancholia finds nothing amusing except the sight of the evil fairy Fata Morgana flat on her back, for which indiscretion she condemns him to fall in love with three oranges. The oranges, when found, turn out to house three beautiful princesses, two of whom at once die of thirst, while the third is saved only by a bucket of water provided by the so-called Eccentrics in the audience (roughly, the untroubled theatre-lovers): and so on. The nuances come thick and fast. Yet, as in any good pantomime, narrative logic is never quite sacrificed to magical intervention; it’s merely speeded up by it. And speed is a strong feature of David Fielding’s production at the Grange: speed in the sense of stage choreography, and in the sense of quick-witted integration of hybrid elements.

Fielding does his own designs, and their eclecticism fits the spirit of the score exactly; in fact a lot of the visual jokes are already in the stage directions. Some directorial clichés, like the inevitable cloned bearded doctors with stethoscopes, are after all justified by the story. Other modernisms, the princesses’ giant orange-juice cartons (“two for the price of three” – why not three for the price of two, by the way?), or the Dr Who phone box that whisks the Prince away to the wicked Creonta’s kitchen, are bang on the Prokofiev nail, if beyond his ken. The magic flashes and fizzes in the best pantomime tradition, and the fake audience groups are brilliantly organised, as well as sparklingly sung, on and off stage, not least in the set pieces – like the famous march and scherzo – which ultimately suggest Prokofiev was more at home in ballet than opera, for all the deftness of this particular specimen.

Musically there is a strong performance waiting in the wings here. The cast is too big to itemise, but Clive Bayley’s King of Clubs, Jeffrey Lloyd-Robert’s Prince, and Wynne Evans’s Truffaldino shouldn’t go unmentioned. Of three very nubile princesses, the survivor, Rosie Bell, hits off the delicious absurdity of the situation to a tee. Vuyani Mlinde’s top-hatted magician Tchelio and Rebecca Cooper’s tall, sexy Fata Morgana are a perfectly matched pair – an illusionist and his assistant gone to the bad. All clever, well-observed, well-sung portraits.

Leo Hussain, a young conductor I haven’t encountered before, is well on top of the score, without quite holding the lid on its volume, which sometimes makes life hard for his singers. But what’s hardest of all for them is the inexplicable decision to sing the opera in (rather bad) French, a language that has no relevance to either the work or its audience. Sure, it was premiered in French in Chicago; but that was for local reasons. This is a Russian opera, a comedy to boot, and the only sane language to sing it in in England is English. The audience might then manage to laugh in the right places, and much, much more often; because as well as being musically a treasure, The Love for Three Oranges is, or should be, very, very funny.

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Comments

...

...