Perhaps the most memorable of the stage designs Peter Pabst created for Pina Bausch is back in London after nearly 20 years: a sea of erect pink silk carnations, the Nelken of the title. It’s canonical that there are 8,000 of them, but only the backstage team know the truth of that.

As the piece opens, dancers start to appear in formal attire, carrying chairs, picking their way through the flowers and sitting down in silence, expectantly. Then Richard Tauber sings Franz Léhar’s “Schön ist die Welt” (The world is beautiful). Over the next two hours the piece will turn that idea into a kaleidoscope of different elements and perspectives, though no final resolution of the patterning is offered.

Bausch’s working method was to ask her squad individually a long list of questions, coaxing them into being honest in their responses. For 1982's Nelken, whose latest run opened on Valentine’s Day, the questions were mostly about love — how the dancers imagined it, what their first love was, how they reacted if forced to love. Bausch would end up with a welter of answers to base her choreography on.

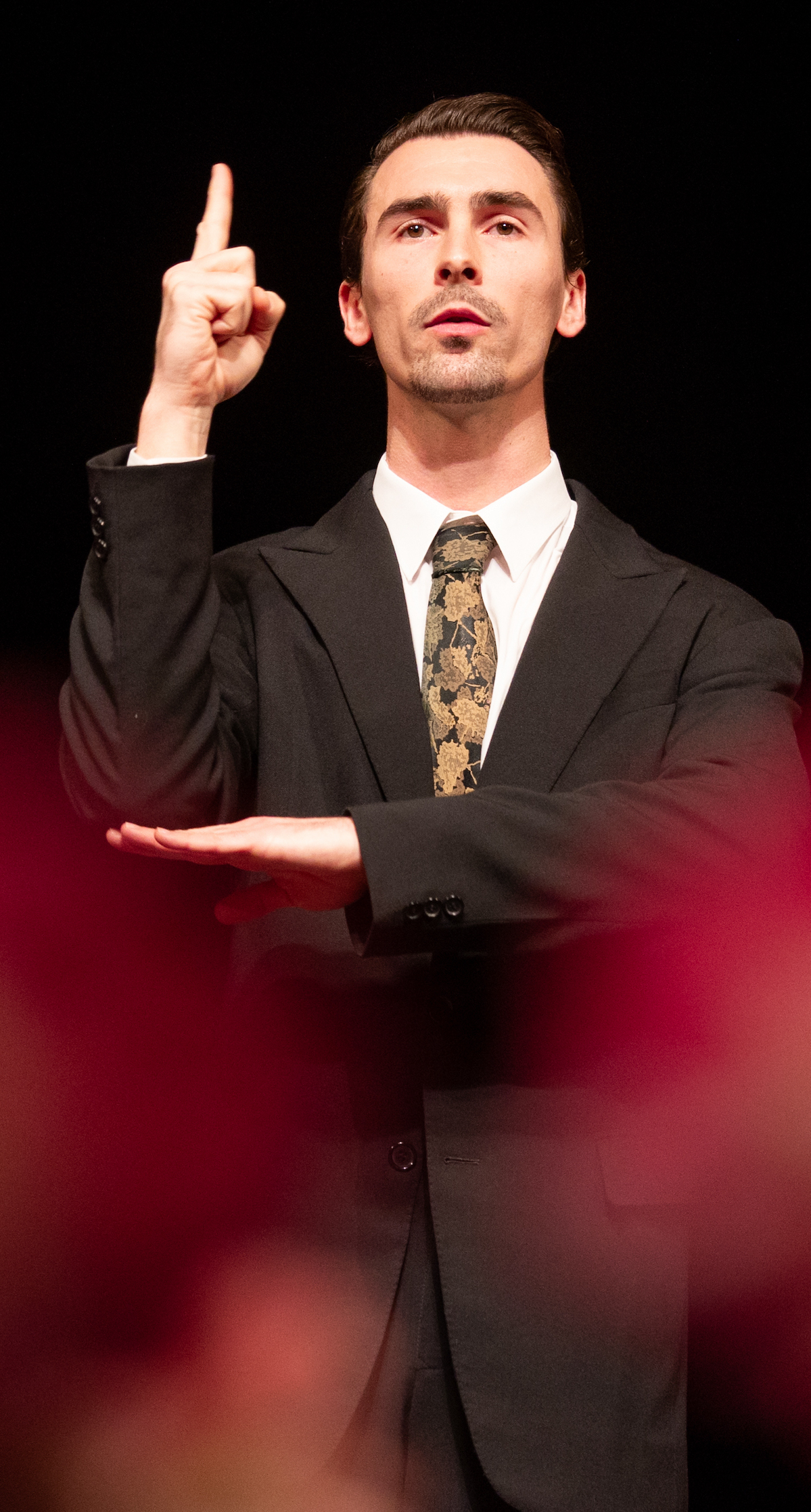

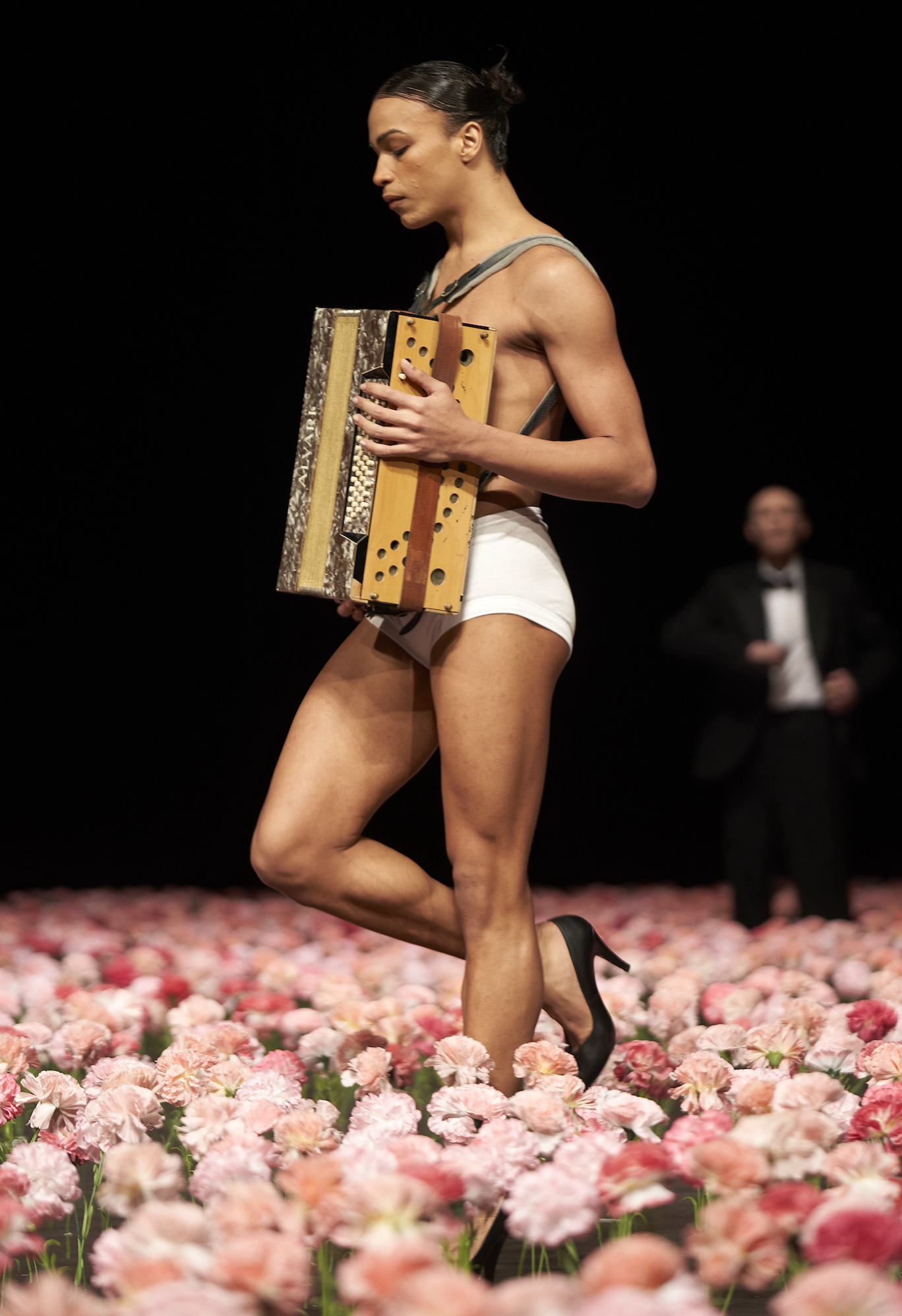

The work, reflecitng this methodology, progresses in episodes, some repeated. These can involve the whole company, small groups or even a solo performer, as in the enigmatic appearances of a dancer carrying an accordion (Naomi Briton, pictured below, left) or the poignant version of Gershwin’s “The Man I Love” that appears early in the piece and is reprised later. It’s performed by a male dancer (Reginald Lefevbre, pictured right) in universal sign language.

The work, reflecitng this methodology, progresses in episodes, some repeated. These can involve the whole company, small groups or even a solo performer, as in the enigmatic appearances of a dancer carrying an accordion (Naomi Briton, pictured below, left) or the poignant version of Gershwin’s “The Man I Love” that appears early in the piece and is reprised later. It’s performed by a male dancer (Reginald Lefevbre, pictured right) in universal sign language.

The initial calm and beauty, with love in the air, doesn’t last. Soon an imperious man in a tuxedo (Ashley Chen on opening night) is checking everybody’s heartbeats with a microphone and demanding their passports. Four Alsatians arrive, with handlers, patrolling the perimeter of the space, while a handful of the men, now in women’s frocks, play at being rabbits, bunny-hopping through the flowers. This idyll is disrupted by Chen sending them offstage.

Before long, two tall metal towers have appeared, with cardboard boxes formed into two chunky cubes beneath them, while a woman rushes around increasingly desperately, trying to stop what’s happening, though she doesn’t seem to know exactly what it is. Four stuntmen then jump down from the towers onto the boxes. It’s no surprise to discover this scenario was inspired by Bausch’s visit to the Berlin Wall.

As is the way with her work, the tone seesaws from moment to moment. Smiling dancers pick members of the audience and lead them out of the exits (amazingly, all agree to go; they were allowed back), which seemed to amuse the opening night audience but would probably give people who had dealt with the Stasi private nightmares. A man force-feeds a woman an orange; a dancer is blackmailed by Chen into becoming a dog, running on all fours.

Then the company start playing the children’s game Grandmother’s Footsteps, here given its French name, Un, Deux, Trois, Soleil! All the cast are wearing frocks. which seems to suggest it's a level playing field. But a bossy leader emerges (Lefebvre). His dominance is soon challenged by the others, who eventually learn how to depose him. Most vocal is a mouthy woman sitting on a man’s shoulders, her long gown covering all but his lower legs, which makes her look, both comically and grotesquely, like a female giant, an expression of her need to outstrip all the others.

The “Tanz” elements of the piece erupt throughout, first in a comic dance on a table top started by the women, bent over so their arms look like legs; they are soon driven away by some of the men, who perform the dance themselves while the woman retreat under the table to dance there instead. Sexual politics as an elephant dance on a table.

In the most spectacular sequence, initially to Schubert’s “Death and the Maiden” quartet, the dancers form a long line on wooden chairs in a sort of seated chorus line that sways arms and legs in unison, or holds its arms over its head as if in prayer: a passionate series of movements that is nevertheless contained and regimented. The dancers move the chairs, reform them, add jumps, later repeat the moves in a circle. It’s choreography that defies what is happening around it and determinedly continues.

In the most spectacular sequence, initially to Schubert’s “Death and the Maiden” quartet, the dancers form a long line on wooden chairs in a sort of seated chorus line that sways arms and legs in unison, or holds its arms over its head as if in prayer: a passionate series of movements that is nevertheless contained and regimented. The dancers move the chairs, reform them, add jumps, later repeat the moves in a circle. It’s choreography that defies what is happening around it and determinedly continues.

In isolation, the dancers are much less confident and harmonised. A routine created by founder dancer Dominique Mercy, now performed by Simon Le Borgne, has lost none of its savage humour, a middle-finger salute to his ballet training, where he berates the audience for treating him as if he were a performing seal while mockingly giving them what they want: a grande tournée, a grand jeté, a chainé, all beautifully executed. In other sequences a despondent Le Borgne is taught how to express despair, another dancer moving his hands up to clutch his head and swaying his arms up and down. He is learning the standard body language of adult life, and its emotions too. Childhood spontaneity is receding.

Weaving among them is Chen with his mic, probing and bossing, spreading unease. In a triumphal moment he marches through the dancers holding spray cans aloft, shooting out jets of mist. But the mood eventually lightens as the Nelken Line appears, to a slow Louis Armstrong number: a sequence, thanks to a company video, that has been taken up around the world, in which the dancers parade slowly, making hand gestures that signify the four seasons. Things grow even jollier when the audience is asked to stand and join in a move involving opening their arms separately, then closing them (not easy in a packed auditorium, sadly.)

The love that hung in the air at the start has, by the final tableau, become a complicated proposition, epitomised by two dancers who alternate kisses and slaps on the other’s cheeks. The carnations are battered and flattened. As the dancers group for a final snapshot, arms raised in a fifth position port de bras (pictured right), they one by one reveal why they became dancers — “Chance”, “My teacher said, ‘Give up now’”, “Dancing made me successful at parties”. The delivery is the usual Wuppertal mix of sass and sadness.

The love that hung in the air at the start has, by the final tableau, become a complicated proposition, epitomised by two dancers who alternate kisses and slaps on the other’s cheeks. The carnations are battered and flattened. As the dancers group for a final snapshot, arms raised in a fifth position port de bras (pictured right), they one by one reveal why they became dancers — “Chance”, “My teacher said, ‘Give up now’”, “Dancing made me successful at parties”. The delivery is the usual Wuppertal mix of sass and sadness.

The company is now stocked with gifted young dancers who weren’t coached by Bausch. Two of its older members have directed rehearsals, using performance videos and the notes made in Bausch’s “director’s book”, teaching the newbies as they were taught. Nelken isn’t a piece that allows the performers to showcase themselves as readily as, say, 1980 or Viktor— and part of the process of becoming a Pinaholic is engaging with the dancers, not as actors but as real individuals. We are still at the getting-to-know-you stage with this intake. But there are promising performers among them who seem to understand their mission. If they are like their predecessors, we could be greeting them as old friends in their fifties and sixties. The piece itself is an indelible classic, Bausch in all her enigmatic complexity, stiil landing its punches.

Nelken at Sadler’s Wells until February 22

More dance reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment