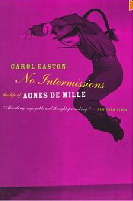

In dance heaven, poor Agnes de Mille is resigned to being jostled by nobler colleagues. "Sprightly but peripheral" was her own assessment of her work, yet, with her 1942 ballet Rodeo and her musicals Oklahoma!, Carousel, Brigadoon and more, she invented a genre of popular stage dance that came to dominate the Western public's theatre-going for half the century.

In dance heaven, poor Agnes de Mille is resigned to being jostled by nobler colleagues. "Sprightly but peripheral" was her own assessment of her work, yet, with her 1942 ballet Rodeo and her musicals Oklahoma!, Carousel, Brigadoon and more, she invented a genre of popular stage dance that came to dominate the Western public's theatre-going for half the century.

She swept away swans and fairies, and gave us new heroines: cowgirls. This was too folksy for the stern electors of modern dance or classical ballet, and yet, both then and now, debts are owed to Miss de Mille in high places. Antony Tudor, one of the great ballet innovators, was influenced by their early friendship when he made his pre-War psychological works at Ballet Rambert - works which opened the way for Kenneth MacMillan.

Today Matthew Bourne's vernacular rewrites of ballet classics glance back at de Mille. But how colourless this dance generation seems in comparison. What is the equivalent nowadays of growing up in a desert called Hollywood where your Uncle Ce and his friend Samuel Goldfish (later Goldwyn) are rounding up extras fro the main street to put in front of their camera? Agnes's father, the playwright William, described Cecil B's first effort, The Squaw Man (1914) as "the first really new form of dramatic storytelling that had been invented for some 500 years... a potential theater of the whole people."

His riproaring daughter was to be almost as inventive. The first all-powerful showbusiness woman in the archetypical man's world, she also made a 45-year marriage in which "I was never bored", and then educated millions of Americans to switch on to dance with her brilliant television programmes and books.

And she was such a likeable monster. Rich and clever, she had frizzy red hair, a big nose, a short stumpy body that she forced to dance, and a surprising sex appeal. Because she felt guilty about sex, but had a terrific appetite for life, there are a lot of frustrated boyfriends in this book (at one point she had two in London and two in New York simultaneously).

She was a whirling typhoon of bitchiness and grievance, and yet disarming. Alongside the fearless insults, there was an exact, unafraid appreciation of her peers' abilities. She knew that she was outclassed by Martha Graham, Jerome Robbins and George Balanchine, by Antony Tudor and Frederick Ashton. Although hurt, she could take it when her husband, Walter Prude, opined lightly that Graham's work was more important than hers.

She was by all accounts a magnetic, inspiring performer - the reviews here of her early solo "recitals" (the form in which dance emerged in New York in the 1920s) make no doubt about that. She was not an inventor but she appropriated ballet and everyday movement and gesture in an individual way that reached straight to the heart of audiences both simple and sophisticated. You recognised a de Mille ballet not by its style but by its attitude, pointed out one critic.

We cannot see much of her work today, because arrogant Agnes of the movie dynasty failed to see that filmed dance had to be different, less central to the action than on stage. Most of her musicals were rechoreographed for the cinema versions. Where we can find her, though, is not so much in this biography, diligent though it is, as in her own superbly catty, effortlessly broad-ranging biography of her idol-competitor, Martha Graham (Martha, published 1991 by Hutchinson). De Mille wrote it in old age, defying a paralysing stroke, and it has all the sway and yeasty allure that Easton's dutiful style lacks (also, oddly, some significant events that this book ignores).

Easton is a fact-collector and letter-extracter, not a natural sensitive; she dives into cod-psychology to expound de Mille's early sex hang-ups and then flinches from the most interesting questions, the relations with Graham, and how in hell her marriage survived. Walter Prude was withdrawn and highbrow, Isaac Stern's concert agent; how did he and their son, Jonathan, remain sane with the woman we see here? Maybe it was that unsentimental honesty of hers that was the glue.

De Mille's dances were about girls with swirls and men who were men; and they came to look quaint in revival. So, of course, did Graham's pioneering modernism. And de Mille, you can see from Martha, was more upset about Graham's fate than her own. In many ways, de Mille remains a privilege to read about.

This review was originally published in the Daily Telegraph, July 12 1997

Add comment