Success in running a large and expanding dance-house enterprise requires knowing when to play safe and when to play with fire, trusting that your audience will come with you. Sadler’s Wells’ annual Flamenco Festival is now such an established feature of the dance calendar that you can usually guess what the opening show will be: a major company with ranks of befrilled backing dancers, a hefty squad of guitarists, box-thwackers and hand-clappers, and at least two or three raucous singers, not to mention the star bailaora and her attendant men. Not this year. This year the opening spot was given to a single, and distinctly singular dancer, Rocio Molina, accompanied by just two guitars. Three people on stage, rarely all at the same time and mostly in the dark. What’s more, the show’s title appeared to be untranslatable.

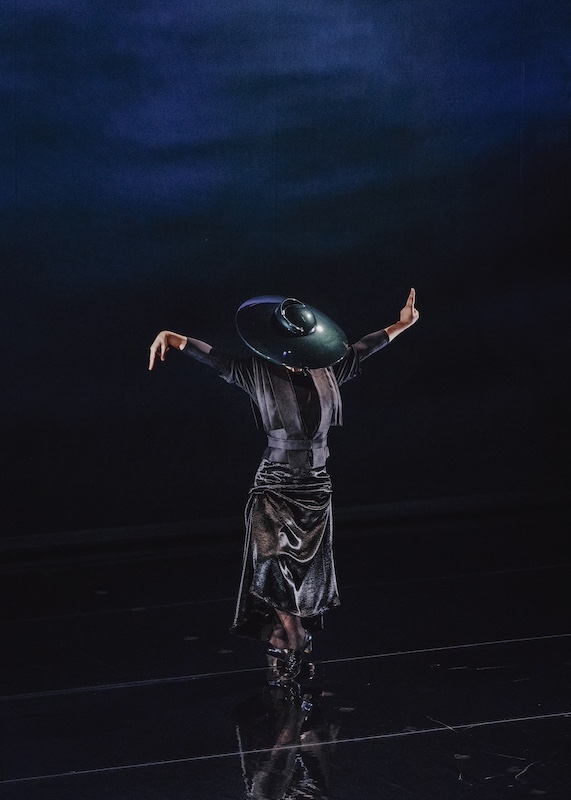

In the tradition-fixated world of flamenco, Molina is a mould-breaker and maverick. Not for her the focus on a mythical gypsy past and its blood feuds. She positions herself firmly in the present, and the passions that fire her dancing are existential. As for her look, forget the frills and shawls – she goes by the Lady Gaga playbook. Face coverings are a favourite: a sombrero (pictured right) fashioned like a shiny black flying saucer, pulled so far over her nose that little eye holes are needed; a gimp mask in a crazy red flower print (pictured below) matching that of her dress, her tights, the entire stage backcloth, and a pair of gloves which she peels off and tosses away, stripper-style. As the show progresses, a quest for self-identity seems to emerge as a theme. But for at least the first 10, even 15 minutes, you wonder where on earth this might be going, and if it is indeed going anywhere, whether it will get there in time.

In the tradition-fixated world of flamenco, Molina is a mould-breaker and maverick. Not for her the focus on a mythical gypsy past and its blood feuds. She positions herself firmly in the present, and the passions that fire her dancing are existential. As for her look, forget the frills and shawls – she goes by the Lady Gaga playbook. Face coverings are a favourite: a sombrero (pictured right) fashioned like a shiny black flying saucer, pulled so far over her nose that little eye holes are needed; a gimp mask in a crazy red flower print (pictured below) matching that of her dress, her tights, the entire stage backcloth, and a pair of gloves which she peels off and tosses away, stripper-style. As the show progresses, a quest for self-identity seems to emerge as a theme. But for at least the first 10, even 15 minutes, you wonder where on earth this might be going, and if it is indeed going anywhere, whether it will get there in time.

The show starts with a blackout, a blackout so complete it feels alarming. A single guitarist, dimly visible, plucks a fierce repeated octave, and when Molina appears distantly through the gloom, after what seems an age of waiting, she does virtually nothing. The glimmer of her black satin sheath of a skirt is all that tells us she is still in the building. What are we waiting for? Who knows? Perhaps she is playing tricks with us. Our ears tell us she is scraping slow circles with her steel toe-cap, a traditional indication that a flurry of rapid-fire zapateado is imminent, but that doesn’t happen. The darkness and the scraping persist.

Of course things do get going, after a fashion. Molina’s arms and wrists are the first to move, at first twining slowly, then revving into a witchy semaphore of roly-poly hands, whirring so fast they become a white blur before subsiding once more into stillness. The next wake-up moment is a convulsion of warrior moves, the kind that, in a CGI action movie, would slay a legion of enemy combatants in half a second. You long for her to do it again, but she doesn't. Instead, she nods to other unrelated movement styles, but again so briefly that you barely have time to clock them. Meanwhile, the two guitarists, Oscar Lago and Fran Vinuesa, seated on either side of the stage, are finally finding their mojo, and their sustained speed and volume is thrilling, with each calling encouragements to the other. Molina criss-crosses the stage, dividing her attention between them. Stamping and turning within inches of each guitar, at one point she reaches out to tap a rhythm on the belly of the instrument. Whether this is meant as a provocation or a sign of camaraderie it’s hard to tell, but it ups the ante either way.

Of course things do get going, after a fashion. Molina’s arms and wrists are the first to move, at first twining slowly, then revving into a witchy semaphore of roly-poly hands, whirring so fast they become a white blur before subsiding once more into stillness. The next wake-up moment is a convulsion of warrior moves, the kind that, in a CGI action movie, would slay a legion of enemy combatants in half a second. You long for her to do it again, but she doesn't. Instead, she nods to other unrelated movement styles, but again so briefly that you barely have time to clock them. Meanwhile, the two guitarists, Oscar Lago and Fran Vinuesa, seated on either side of the stage, are finally finding their mojo, and their sustained speed and volume is thrilling, with each calling encouragements to the other. Molina criss-crosses the stage, dividing her attention between them. Stamping and turning within inches of each guitar, at one point she reaches out to tap a rhythm on the belly of the instrument. Whether this is meant as a provocation or a sign of camaraderie it’s hard to tell, but it ups the ante either way.

Aficionados might possibly detect some repertoire “standards” within this unconventional 70 minutes – a slow and pensive soleá, and a segment decked out in the traditional bata de cola, a dress with a long, stiff snaking train that she kicks about as if it’s a bit of a nuisance, then scoops up and hugs to her chest as if it were a large parcel while her feet work frantically below. But it’s clear that Molina prefers to keep her audience, if not entirely in the dark, then gently bemused.

The final section of this show begins with the sound of her giggling – at first so quietly that it could be the sound of a guitarist’s fingernail on a string, then more openly, and at length. What was she laughing at? The absurdity of her costume, of 1600 people crowding into a black box for 70 minutes to watch her in the dark, the absurdity of existence? Whatever it was, Rocio Molina won over that first-night crowd. There was no misreading the eruption of cheering. For myself, I’m not sure I’ve ever felt so mystified by an evening of dance, while at the same time strangely uplifted. Al fondo rieja (lo otro del uno) indeed.

Add comment