The Royal Opera House is on fire this month. Not literally (unless someone knocks over the flaming braziers outside) but with the varied illuminations of the Deloitte Ignite Festival, co-curated by the Royal Ballet and Minna Moore Ede of the National Gallery. The theme this year is Myth, and specifically Leda's rape by Zeus in swan form, and Prometheus's gift of fire to humanity. Artworks dealing with these two stories, or with swans and fire more generally, are to be seen all over the building, which this weekend was open during the day for a variety of public events, from film screenings to live choreography sessions to yoga in the Paul Hamlyn Hall. Downstairs in the Linbury Studio Theatre, the Royal Ballet presented a selection of dance pieces, new and old, and three specially commissioned films, all illustrating or retelling a mythical story.

The various extracts from existing pieces are – with one exception – well chosen, and boast a remarkable array of principals. We got the encounter between the Tsarevich (Bennet Gartside) and the Firebird (Roberta Marquez) from the ballet of the same name, the Dying Swan solo (Marianela Nuñez), the lyre solo from Apollo (Federico Bonelli), the final moments from Ondine (Yuhui Choe and Valeri Hristov), and the pas de deux between the Prince (Liam Mower) and the Lead Swan (Edward Watson) from Matthew Bourne’s Swan Lake. All were done well, with the standouts being Nuñez’s swan and the Ondine excerpt, which brilliantly showcased Ashton’s genius for embedding concise storytelling in his steps, rather than hanging the one on the other.

The pas de deux of the Raven Girl (Sarah Lamb) and the Raven Prince (Eric Underwood) from Wayne McGregor’s Raven Girl (pictured right) was my exception to the good choices. Though it’s a moment of rare emotion in the context of the rest of the work, isolating it here exposes how close to sadistic its hyper-contorted choreography is. Lamb and Underwood execute the difficult moves flawlessly, but with barely a flicker of warmth or emotion. Raven Girl, which is neither a myth nor a fairytale but a Kafka-esque fable, shows the impossibility of creating new myths in the 21st century; its story of highly individuated unhappiness sits uneasily beside the rest of the evening’s offerings from the tropes and types of classical mythology and 19th-century supernatural fantasy.

The pas de deux of the Raven Girl (Sarah Lamb) and the Raven Prince (Eric Underwood) from Wayne McGregor’s Raven Girl (pictured right) was my exception to the good choices. Though it’s a moment of rare emotion in the context of the rest of the work, isolating it here exposes how close to sadistic its hyper-contorted choreography is. Lamb and Underwood execute the difficult moves flawlessly, but with barely a flicker of warmth or emotion. Raven Girl, which is neither a myth nor a fairytale but a Kafka-esque fable, shows the impossibility of creating new myths in the 21st century; its story of highly individuated unhappiness sits uneasily beside the rest of the evening’s offerings from the tropes and types of classical mythology and 19th-century supernatural fantasy.

Of the three short dance films, all dealing with Leda and the Swan, Kim Brandstrup’s was the standout, picking up on the complexities of divine-mortal union by intercutting two poems by WB Yeats, "Leda and the Swan" and "The Mother of God". Tommy Franzen and Royal Ballet dramatic heavyweight Zenaida Yanowsky dance with each other on top of a stone block that could be a bed, a tomb or an altar, and there are two distinct sections, with each getting a chance to project desire, aggression, and submission. The “flying” with which both sections end is a masterstroke – sexy, unsettling, and unforgettable.

The two new pieces, both essentially contemporary in style, eschewed swans and spirits in favour of more primal and elemental mythical material. Miguel Altunaga, one of Rambert’s most electric dancers, had cast himself and two Rambert colleagues, Estella Merlos and Hannah Rudd, as the Fates in a piece called Dark Eye that fizzed with energy and atmosphere. The dark blankness of the Linbury stage was turned into an advantage, a suggestion of the vast, gloomy cavern we imagine the Fates to inhabit, while ingenious downward spotlighting created the illusion of grey, rainy landscapes for the sisters to journey through. A low-to-the-ground flexible contemporary choreographic language, more “natural” than ballet, fits perfectly with the idea of the Fates, who come before anyone, even the gods. Twisting, writhing, crawling, exploding apart, then coming together in witchy communion, and making a feature of white, claw-like hands against their dark cloaks, the three dancers were mesmerising, and the piece as a whole highly successful. It’s a simple conceit – effectively an atmosphere piece exploring the weirdness of these mythical beings – but executed brilliantly.

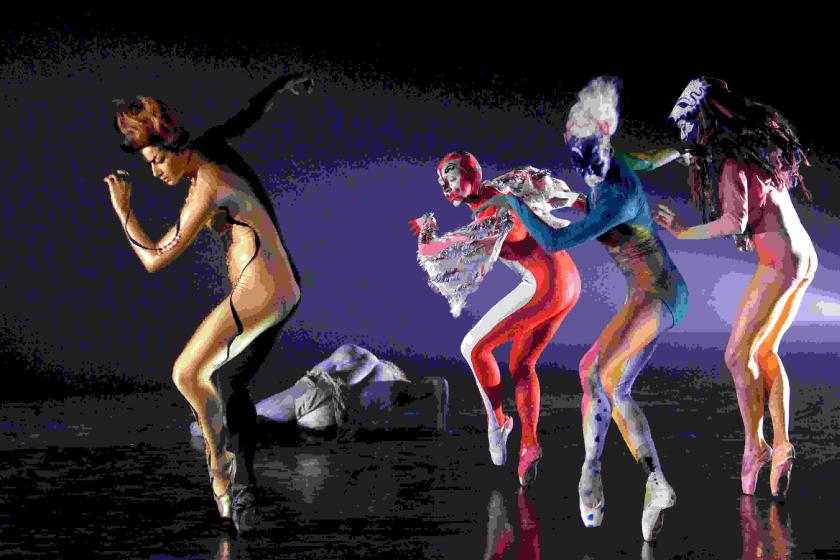

Aakash Odedra’s piece, Unearthed, suffered from a dire lack of simplicity. A take on the Prometheus myth, it featured a creator figure (Prometheus?), who at one point dug his hands into a pile of clay, a dancer representing his creation (homo faber? Human culture?), and six dancers representing different aspects of fire. I learned more about these latter from Marina Warner’s commentary at the beginning than from the piece itself: in garish costumes (main picture) painted by Chris Ofili (in some cases directly onto their skin), they looked like hideous X-Men and had very little of interest to do, dance-wise. The grey, black and white costumes of Prometheus and Man, whose dotted and daubed patterns suggested African and aboriginal witch doctors, were more evocative, and those two characters also had more weight to their choreography – Marcelino Sambé's Man (pictured above left) in particular a tour de force of intensity.

Aakash Odedra’s piece, Unearthed, suffered from a dire lack of simplicity. A take on the Prometheus myth, it featured a creator figure (Prometheus?), who at one point dug his hands into a pile of clay, a dancer representing his creation (homo faber? Human culture?), and six dancers representing different aspects of fire. I learned more about these latter from Marina Warner’s commentary at the beginning than from the piece itself: in garish costumes (main picture) painted by Chris Ofili (in some cases directly onto their skin), they looked like hideous X-Men and had very little of interest to do, dance-wise. The grey, black and white costumes of Prometheus and Man, whose dotted and daubed patterns suggested African and aboriginal witch doctors, were more evocative, and those two characters also had more weight to their choreography – Marcelino Sambé's Man (pictured above left) in particular a tour de force of intensity.

The arc was some kind of creation story, but the slow opening (clearly the “without form, and void” part) was far too long, a tedious exercise in enduring white noise (Talvin Singh’s score) and waiting for something to happen. The suggestions of primordialism, the (eventually) percussive score and the stamping-based choreography all make inevitable comparison with the Rite of Spring, but only to Unearthed’s disadvantages: it succeeds in being neither profound nor exciting. I’d have expected better from Odedra, a talented and thoughtful young choreographer, but I wonder whether – like 2012’s Diana and Actaeon (coincidentally also boasting garish unitards by Ofili) – there were too many cooks involved and the broth got overboiled.

Though Marina Warner's narration offered some interesting facts and observations, particularly about birds (which seem to be a love of hers), Sampling the Myth was clearly intended to be less a profound exploration of the nature of these stories than simply a joyful introduction to the fertile worlds of both myth and dance. In that, it succeeded admirably.

- The Deloitte Ignite Festival runs at the Royal Opera House until 28 September

Add comment