The Lost Leonardo review - an incredible tale as gripping as any thriller | reviews, news & interviews

The Lost Leonardo review - an incredible tale as gripping as any thriller

The Lost Leonardo review - an incredible tale as gripping as any thriller

The machinations of the art market laid bare

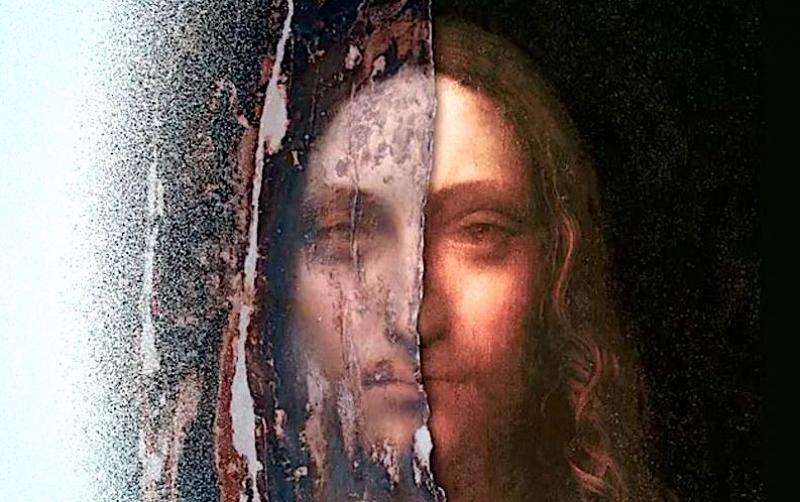

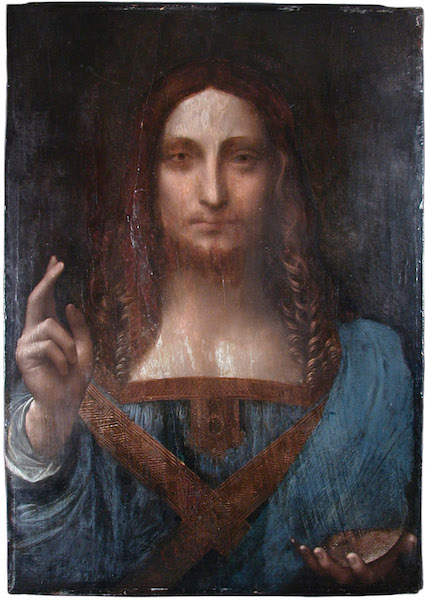

It’s been described as “the most improbable story that has ever happened in the art market”, and The Lost Leonardo reveals every twist and turn of this extraordinary tale. In New Orleans in 2005, a badly-damaged painting (pictured below left) sold at auction for $1,175.

Even Parish admits the idea was ludicrous. “To say I’ve found a picture like this is, in our circles, akin to saying I had a spaceship on my lawn last night and I saw some unicorns. It’s just so far-fetched; don’t even try to convince yourself because you’re going to look like a fool!” But convince themselves they did, along with a host of others – so much so that, 12 years later, the picture fetched a staggering $450 million at a Christie’s auction in New York and broke every record in the book.

Andreas Koefoed, director of this fast-paced documentary, interviews the key players and, through their recollections, pieces together the murky train of events that brought about this stratospheric rise in value. As dealers, art historians, museum curators, restorers, critics and journalists tell their side of the story, a picture emerges of judgements clouded by ambition, greed, desire and expediency. The revelations come thick and fast and no-one emerges smelling of roses.

Andreas Koefoed, director of this fast-paced documentary, interviews the key players and, through their recollections, pieces together the murky train of events that brought about this stratospheric rise in value. As dealers, art historians, museum curators, restorers, critics and journalists tell their side of the story, a picture emerges of judgements clouded by ambition, greed, desire and expediency. The revelations come thick and fast and no-one emerges smelling of roses.

London’s National Gallery played a crucial role in setting the ball rolling. Luke Syson included Salvator Mundi in the Leonardo exhibition that he curated for the museum in 2011, claiming unequivocally that the picture was the genuine article. He had no evidence, but that didn’t discourage him from making the bold assertion that launched this dubious picture on its way to glory.

At the press view, I gazed into the eyes of Christ and thought, “If this picture is a genuine Leonardo, I’m a rhinoceros.” I may not be a Renaissance scholar but, by then, I’d been making, looking at and writing about art for over 40 years and the painting I stood in front of had no authority, no presence and no inner life. Christ looks like a woman in drag, complete with breasts, and, in my view, the image is sentimental kitsch. I’m not alone. “It’s not even a good painting,” exclaims Jerry Saltz, Pulitzer prize-winning art critic. “It’s a made-up piece of junk.”

Restorer Dianne Modestini (pictured above right) was the first to claim it as an original; she spent five years painstakingly retouching the picture then several more promoting it. According to Renaissance expert Frank Zöllner, the result is paradoxical. "The light is very good,” he says, “but this is the part that’s been restored; so it’s a masterpiece – by Dianne Modestini.” New York critic, Kenny Schachter recalls “the joke circulating the art world – that it was a contemporary painting, because 90 per cent of it was painted in the last 10 years during the restoration process.”

Parish and Simon tried to place the picture in a museum but, despite the National Gallery’s endorsement, none would buy it. So they sold it to the broker Yves Bouvier, who passed it on to Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev, making a cool $44.5 million profit in a single day. As the perspective shifts to international wheeler-dealing, things become murkier and more surreal. And as it strays into the realms of tax evasion, money laundering and global politics, the story gets as far-fetched as a cheap thriller. Like the Wild West, the art market is subject to so little scrutiny that buying art is a fool-proof way of hiding surplus wealth.

Parish and Simon tried to place the picture in a museum but, despite the National Gallery’s endorsement, none would buy it. So they sold it to the broker Yves Bouvier, who passed it on to Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev, making a cool $44.5 million profit in a single day. As the perspective shifts to international wheeler-dealing, things become murkier and more surreal. And as it strays into the realms of tax evasion, money laundering and global politics, the story gets as far-fetched as a cheap thriller. Like the Wild West, the art market is subject to so little scrutiny that buying art is a fool-proof way of hiding surplus wealth.

The man who bid the picture up to that jaw-dropping $450 million was Sheik Mohammad Bin Salman who seems to be using it as a pawn in a game of cultural one-upmanship. The Saudi prince offered to lend it to the Louvre for their Leonardo blockbuster show in 2019 and a booklet by the museum’s director, Jean-Luc Martinez, was produced complete with technical data validating the painting’s status. But the loan fell through and, mysteriously, the booklet was withdrawn. “We don’t want the content of this book to be published,” explains the press officer. “It was connected to the loan, the loan didn’t happen, so there is no book.” No loan, no authentification; what kind of bargain does that imply? Something akin to the Pope selling indulgences?

The identity of the picture described by Christie’s as “the male Mona Lisa” is still contested, then. The story and the skulduggery involved would be comic if the repercussions weren’t far-reaching for art and artists alike. Once art becomes a commodity used primarily by the stinking rich as a safe haven for excess wealth, it is hard to see it any other way. Making art becomes a shady business and the meaning of art appreciation changes from taking pleasure in art to watching it accrue in value. And that is a tragedy!

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment