A man sits at a table in an otherwise bare room. Shot in monochrome and positioned off-centre, he reads a newspaper and smokes a cigar, lazily obscured as two other figures drift into and out of shot. A brief fight ensues. A man falls to the floor and is dragged away. Suddenly, a door opens. A new man stands at the foot of a staircase. It leads to another room, where yet more men await.

This is early Rainer Werner Fassbinder, the first film in the first volume of Arrow’s new collection of his works. The movie’s title is Love Is Colder Than Death (1969), and its opening is typical of a filmmaker renowned for the boldness of his style. Franz is a petty criminal, played by Fassbinder himself – he has come to this place for a meeting with the local crime syndicate. “Will you work for the syndicate?” the blindfolded Franz is asked, without reply. “You will work for the syndicate,” is the syndicate’s answer. Fassbinder has cast himself as hostage, but who is his captor?

One answer is cinema. Fassbinder was among a group of young filmmakers who, throughout the 1960s, had rallied against a perceived stagnation within the German artistic mainstream, a sentiment captured in the Oberhausen Manifesto of 1962. It’s declaration “Der alte Film ist tot. Wir glauben an den neuen” (The old cinema is dead. We believe in the new cinema) announced the arrival of a novel era, to be defined by artistic ambition and social critique, in which cinema was to be liberated from the shackles of commercial gain. Love Is Colder Than Death is, in part, a homage to Oberhausen – in his blindfold, the maverick Franz is both a subject of, and threat to, the dominant institution.

Like Franz, Fassbinder’s unwillingness to bend the knee would earn him a reputation as German cinema’s unruly enfant terrible. His next film, Katzelmacher (1969), offered a stylistic continuation of that bare-bones debut, but a step change arrived in the shape of Beware of a Holy Whore (1971). Here, Fassbinder’s irreverence achieved both its most playful and philosophical form, as he portrayed the backstage dramas of a film cast and crew as they await the funds to continue their production. The plot quite literally "cut", what remains is vacuum.

Like Franz, Fassbinder’s unwillingness to bend the knee would earn him a reputation as German cinema’s unruly enfant terrible. His next film, Katzelmacher (1969), offered a stylistic continuation of that bare-bones debut, but a step change arrived in the shape of Beware of a Holy Whore (1971). Here, Fassbinder’s irreverence achieved both its most playful and philosophical form, as he portrayed the backstage dramas of a film cast and crew as they await the funds to continue their production. The plot quite literally "cut", what remains is vacuum.

The film’s characters struggle with a lack of direction (“If only I knew what I was meant to do”), questions are posed without answer. Others, meanwhile, seek respite from the crush of normality. “I knew what it was like in the womb,” one reports of his drugs high. This is a cinema unhinged from structure, a Kafkaesque reflection of a world without meaning.

Beware of a Holy Whore transforms the economic and formal challenges facing "den neuen" into its very subject matter, establishing a dualism between, on the one hand, the terror of constraint, and on the other, the peril of freedom. These themes are re-visited in The Merchant of Four Seasons (1971), which portrays the downfall of Hans Epp (Hans Hirschmüller), a beleaguered fruit seller in 1950s Munich. Less innovative than its predecessors, the film’s ordinary, working-class protagonist contains a nod to the socialist sympathies buried deep within the psyche of this self-styled "post-war" director, born just three weeks after Germany’s unconditional surrender in 1945.

Yet, to view Merchant primarily via the lens of this anti-authoritarian impulse is to ignore a competing emphasis: of cause and effect. It is Hans’s flaws of character, and those of his family, to which Fassbinder gives the most weight as an irrepressible predictor of their own misfortunes, resulting in a film that is a great deal more psychological than political. This the case, Merchant is more clearly understood as a stepping-stone to Fassbinder’s next feature, and the highlight of the Arrow set: The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972).

Petra (Margit Carstensen) is a fashion designer and recent divorcee. With an all-female cast, the film pursues its eponymous figure in theatre-like fashion through a series of acts, each representing a distinct view into one element of Petra’s capricious psychology, visually rendered in the change of her clothes and hair. The entirety of the film is set within the confines of her bedroom. Amid this tight space, Fassbinder succeeds with crossbeams and bedposts in creating an atmosphere that is rigid and oppressive, while bringing transition and motion to an otherwise unblinking masterpiece of cinematography.

As she polarises between arrogant genius and manic depressive, Petra is gradually revealed as a perennially blank canvas who, much like the mannequins that dot her apartment, readily adopts which feeling or emotion presents itself to her. Fassbinder thus reveals the fragility and self-fashioning inherent in human psychology. Like Nicholas Poussin’s marvellous "Midas and Bacchus", the immense fresco that dominates Petra’s bedroom wall, it proves to be a tale of tragic self-destruction.

As she polarises between arrogant genius and manic depressive, Petra is gradually revealed as a perennially blank canvas who, much like the mannequins that dot her apartment, readily adopts which feeling or emotion presents itself to her. Fassbinder thus reveals the fragility and self-fashioning inherent in human psychology. Like Nicholas Poussin’s marvellous "Midas and Bacchus", the immense fresco that dominates Petra’s bedroom wall, it proves to be a tale of tragic self-destruction.

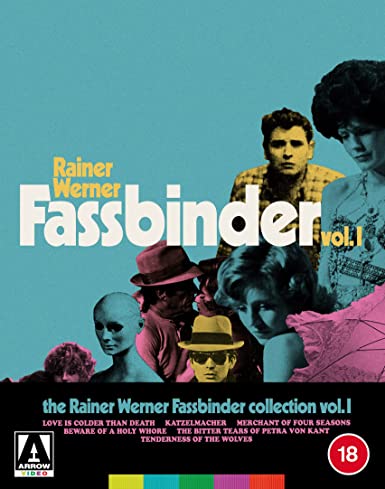

Surprisingly, this volume of the Rainer Werner Fassbinder Collection doesn’t end with a Fassbinder film. Instead, he turned producer for Ulli Lommel’s Tenderness of the Wolves (1973), based on the true story of German serial killer and cannibal Fritz Haarmann (Kurt Raab, pictured above). “There is talk of a werewolf”, says the mother of one boy butchered at Haarman’s hands. Her blend of fear and captivation is not dissimilar to that experienced by Lommel’s viewer, who is compelled to learn more about this subversive historical figure. And is it Fassbinder’s influence, we are left to wonder, that Haarman’s crimes are set upon as a metaphor for the failures of the post-war German state – in which, as one of the characters remarks, there is “Nothing to eat. Nothing to drink”?

Add comment