“Don’t judge a book by its cover,” the John Ford scholar Tag Gallagher quietly observes in the penetrating – and deeply moving – video essay he contributes to Masters of Cinema’s Blu-ray disc of Ford’s 1953 masterpiece The Sun Shines Bright.

It’s good advice. There’s plenty in the movie for cancel culture advocates to sink their teeth into – should they be so blinkered. Gallagher asserts here, as he did in his book on Ford, that the film might well have been titled Intolerance, such is its condemnation of bigotry.

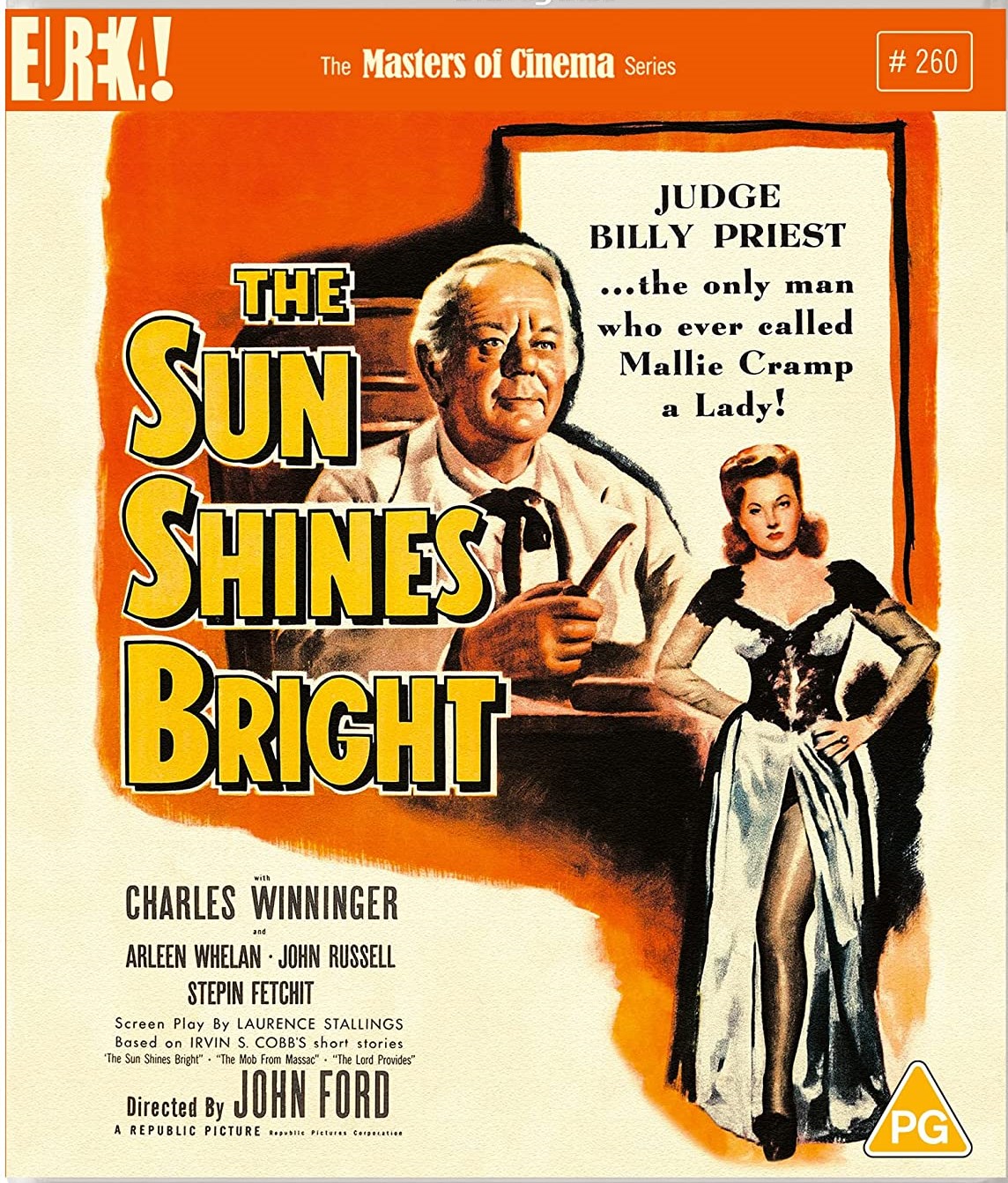

The Sun Shines Bright, which Ford claimed in 1968 was his favourite of his films, was adapted by Laurence Stallings from three of Irvin S Cobb’s stories about the aging Kentucky judge Billy Priest. Charles Winninger assumed the role played by Will Rogers in Ford’s first version, Judge Priest (1935); Stepin Fetchit, allegedly the first African- American actor to become a millionaire (despite his low salaries compared with white actors), played Billy’s loyal factotum, Jeff Poindexter, in both films.

The first was set in 1890, the second in 1905, but life in the fictional town of Fairfield (Cobb’s Paducah) in the post-Civil War Reconstruction era is the same in both. The antebellum hierarchy partially survives in The Sun Shines Bright, and many blacks, like Jeff, don’t question their place in it. The Confederacy’s flag is much in evidence; more disturbingly, Billy's courtroom gives wall space to a portrait of the Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest, who ordered the massacre of black Union troops at Fort Pillow in 1864 and after the war became the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan.

In an early scene, Jeff, who’s been dozing behind the bench, implores a banjo-twanging black youth, US Grant Woodford (Elzie Emanuel) – brought there by his uncle (Ernest Whitman) because he’s idle – to play the Southern anthem “Dixie” instead of the despised Northern tune “Marching Through Georgia”. Jeff whips out his harmonica and as he and the kid play the tune they cavort manically, as if they're on a stage. (Fetchit had been a vaudevillian.) The sound of "Dixie" fills Billy with pride and rallies all of Fairfield’s aged Johnny Rebs. Music is vital to the film's reconciliatory spirit. Ford’s nostalgia is not for the Confederacy's lost cause, but for the doddering old soldiers’ rose-tinted memories of their esprit de corps.

In an early scene, Jeff, who’s been dozing behind the bench, implores a banjo-twanging black youth, US Grant Woodford (Elzie Emanuel) – brought there by his uncle (Ernest Whitman) because he’s idle – to play the Southern anthem “Dixie” instead of the despised Northern tune “Marching Through Georgia”. Jeff whips out his harmonica and as he and the kid play the tune they cavort manically, as if they're on a stage. (Fetchit had been a vaudevillian.) The sound of "Dixie" fills Billy with pride and rallies all of Fairfield’s aged Johnny Rebs. Music is vital to the film's reconciliatory spirit. Ford’s nostalgia is not for the Confederacy's lost cause, but for the doddering old soldiers’ rose-tinted memories of their esprit de corps.

When Billy, restoring order, calls out “boy” – both young US and his uncle step toward him, so ingrained is racist social stratification. The entire sequence isn’t an endorsement of Jim Crow but a commentary on it – including Fetchit and Emanuel’s broad parodying of blackface minstrels parodying blacks. The notion that Jeff and US are stereotypically lazy is deceptive. Jeff runs Billy’s household and manages his schedule, urging him to get to court on time. No fool, US is eager to get work. The film is at its most anxious when he’s wrongly accused of raping a white girl. Billy reluctantly admits him to jail, knowing it’s the only way to protect him.

If there’s any doubt about the sincerity of Ford’s liberalism, he shows the terrified reactions of the poor local blacks when an armed mob, initially unseen, rampages into town to lynch the prisoner. Billy, standing alone before the jail, draws a line in the dirt and tells the mob he’ll shoot anyone who crosses it.

Ford made The Sun Shines Bright primarily because the Fox studio had cut the equivalent sequence from Judge Priest, which was made when lynchings were commonplace. His biographer Joseph McBride mentions on his indispensable voice commentary that, though lynchings had declined by 1953, 14-year-old Emmett Till would be murdered by white men in Mississippi two years later. The recent killings of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery and other black citizens mean The Sun Shines Bright is all too relevant. Astoundingly, it was only yesterday, March 7 2022, that the US Senate passed the Emmett Till Antilynching Act, which makes lynching a hate crime a century after such a law was first broached.

Ford's film centres on factionalism in Fairfield at a time when the glib lawyer son (Milburn Stone) of a Northern carpetbagger is challenging Billy’s re-election bid. After one of his Confederate veteran cronies has swiped the standard of their elderly equivalents in the Grand Army of the Republic – men they fought against 40 years previously – Billy carries it back with due dignity to their “encampment” in a local hall. He gives a magnanimous speech, and takes the opportunity to distribute cards to the Yankee vets, soliciting their votes. It's Billy's ability to move among all folk and negotiate equably with them that makes him a quintessential Fordian hero, the director's idealised version of himself. (Pictured above: Arleen Whelan and John Russell)

Ford's film centres on factionalism in Fairfield at a time when the glib lawyer son (Milburn Stone) of a Northern carpetbagger is challenging Billy’s re-election bid. After one of his Confederate veteran cronies has swiped the standard of their elderly equivalents in the Grand Army of the Republic – men they fought against 40 years previously – Billy carries it back with due dignity to their “encampment” in a local hall. He gives a magnanimous speech, and takes the opportunity to distribute cards to the Yankee vets, soliciting their votes. It's Billy's ability to move among all folk and negotiate equably with them that makes him a quintessential Fordian hero, the director's idealised version of himself. (Pictured above: Arleen Whelan and John Russell)

Given the town’s striving for middle-class respectability, Billy and his supporters (played by Mitchell Lewis, Russell Simpson, Ludwig Stössel, Paul Hurst and Francis Ford, the director's older brother, excelling in his final role) suspect they will lose the election when he grants the wish of the local madam (Eve March) to give a proper funeral to one of her former girls, who as a middle-aged woman (Dorothy Jordan) has returned to the town to die. (Jordan would be equally haunting as another doomed woman, Martha Edwards, in Ford’s The Searchers three years later.)

Billy and his friends have long protected her daughter, Lucy Lee (Arleen Whelan), raised by the town doctor (Simpson), from the knowledge she is the daughter of a prostitute and the granddaughter of their general (James Kirkwood), who refuses to acknowledge her. Ashby Corwin (John Russell), the town’s profligate son and a sort of louche Rhett Butler, is meanwhile courting Lucy, his chivalry betokening his redemption. Ford helps resolve these relationships via an almost silent funeral procession, magnificently staged, that culminates in a burial service and Billy’s dramatic rendering of John 8:7. “He that is without sin among you...”

Despite Billy’s victories, his time is nearly over, and he knows it. Ford grants him a lonely last walk, sustained by cinematographer Archie Stout’s deep-focus shot, that goes in a different direction to John Wayne’s in The Searchers, but is no less elegiac.

Add comment