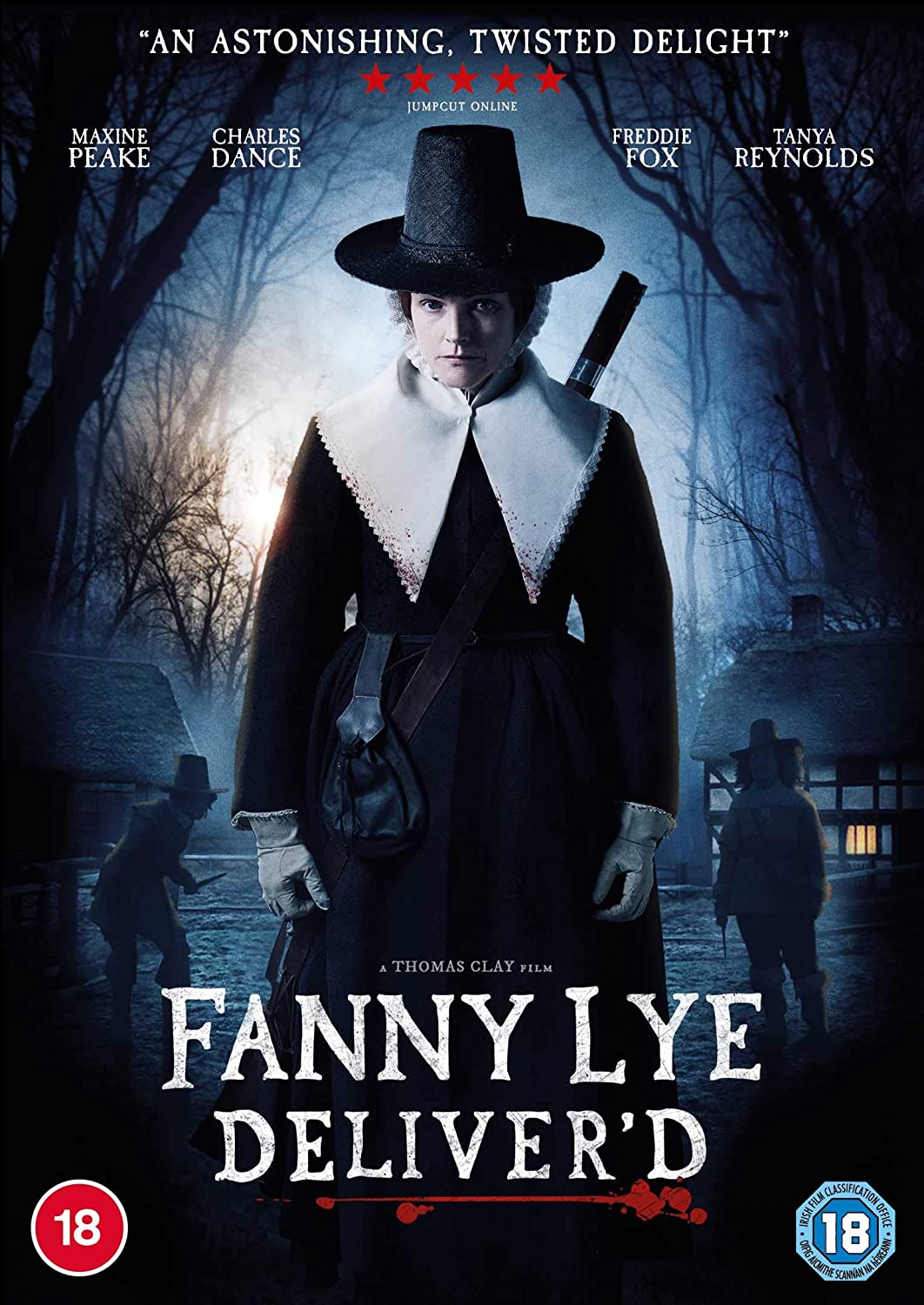

There’s something very familiar and also a little disappointing about Fanny Lye Deliver’d. Set in the years following the English Civil War, the story follows a young couple who enter the home of a stern, God-fearing family, disrupting their lives and their strict sense of right and wrong. This disruption is followed by a larger, more violent confrontation, both events coming to secure the delivery of the title.

Director Thomas Clay's film has clear precedents in classics like Witchfinder General and more recent fare like A Field in England and The Gallows Pole. However, Fanny Lye Deliver’d is no real horror, as most of these have tended to be. Instead, it is closer to a Western, with tropes like the isolated farm, the irruption of the new, and a thick haze of mist that obscures all but the small set of the farmhouses.

Ostensibly, the story focuses on the character of Fanny Lye, played well by Maxine Peake. However, Peake is lost in a plot that could use her far better than it does, at least until the last third of the film. The initial simplicity of her character – indeed, of all the characters – is highlighted by a soundtrack that has all the soupiness of a Western. (It’s personal, I know, but the richness of folk songs or contemporaneous hymns could have worked better to flesh the action out: instead, the score is off-kilter and awkward, its sentimentality only resonating with its allusions to Westerns.) In addition to this almost constant music, the film is overlaid by a strong narrative, read by Rebecca Henshaw (Tanya Reynolds), the young woman we are introduced to at the very beginning, running naked through woods with her man, Thomas Ashbury (Freddie Fox). The narrative is very leading, an ominous foreshadowing of all that is to come, in a slightly too obvious way.

As the film develops, the incomers take over, corrupting staid morality with magic mushrooms and prurient displays of wild abandon. The setting, during the madness and strictures of the interregnum, is fertile ground for the exploration of such a contrast. The fervour of Charles Dance’s Puritan John Lye is a good opposition to Thomas Ashbury’s hedonism, and a reflection of the particular time that they inhabited. Set in 1657, three years before the Restoration, we all know what would ultimately win out.

As the film develops, the incomers take over, corrupting staid morality with magic mushrooms and prurient displays of wild abandon. The setting, during the madness and strictures of the interregnum, is fertile ground for the exploration of such a contrast. The fervour of Charles Dance’s Puritan John Lye is a good opposition to Thomas Ashbury’s hedonism, and a reflection of the particular time that they inhabited. Set in 1657, three years before the Restoration, we all know what would ultimately win out.

Also stalking in the background are two upholders of justice, who are anything but, a gruesome reminder that the law could be just another weapon to use against the defenceless. As they enter the plot more fully, the film comes into its own, allowing Fanny Lye to develop a sense of herself beyond the oppression of her gender by violent male ideologues. There is far more nuance here than in the rest of the film, and the hard-won deliverance of Peake's character is its saving grace. However, unlike the heroes of Westerns, there is no setting sun for her to ride off into. Instead, it is the thick mist of the past, as Henshaw describes her emancipated future. There's no further clarification to hand: this release has no extras.

Add comment