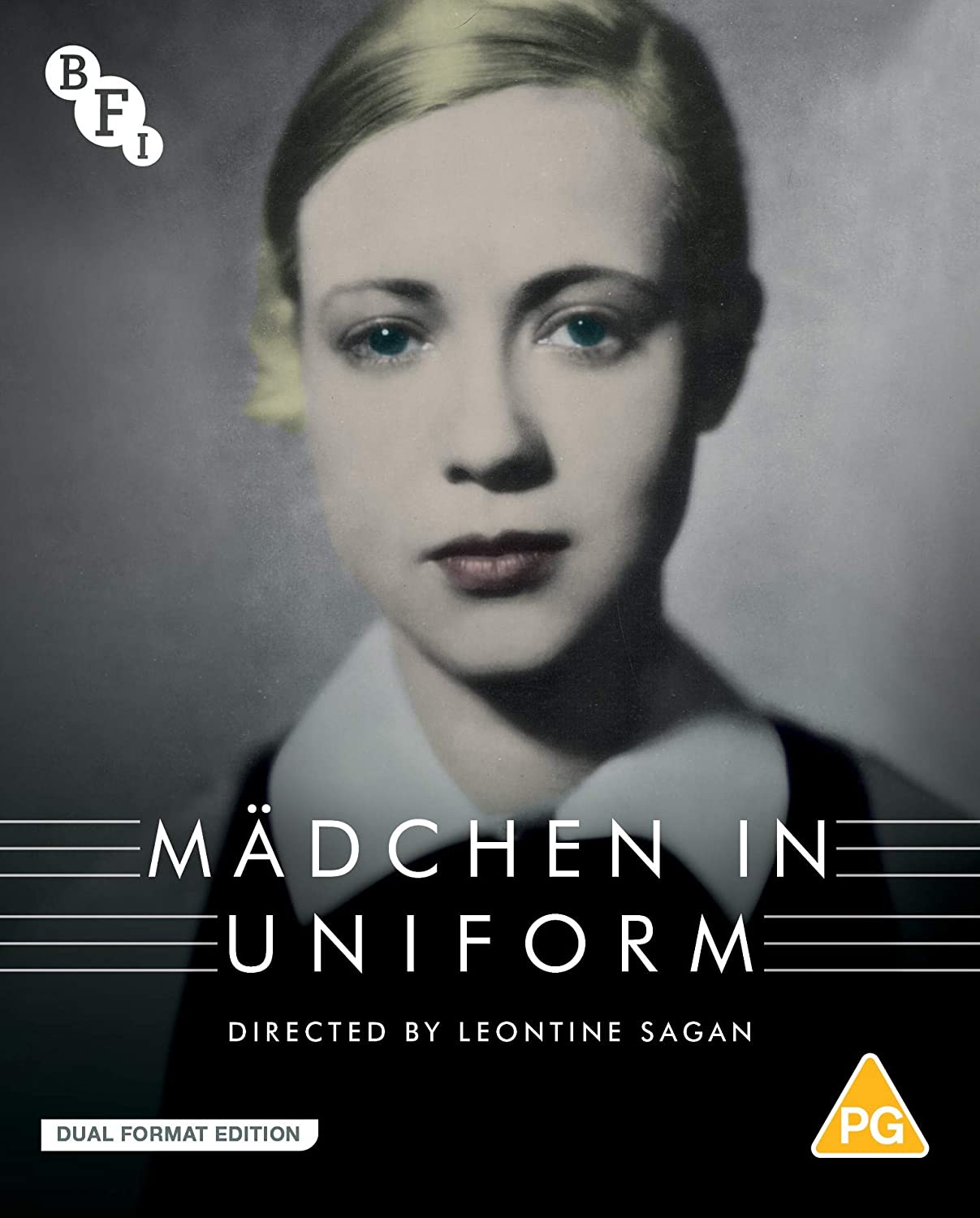

The late Weimar-era film Mädchen in Uniform (1931) was visionary – a delicate Queer love story set in a repressive girls’ boarding school that denounced the Prussian militarist creed as dehumanising. Like The Blue Angel (1930), another German early talkie classic in which sexual energy confronts authoritarianism, Leontine Sagan’s film contained intimations of Nazism.

Foreshadowing the Hitler Youth, the schoolboys who unwittingly steer their complacently bourgeois master toward sexual humiliation and death in The Blue Angel have less corruptible counterparts in the daughters of poor soldiers who attend Mädchen in Uniform’s Potsdam academy. Its headmistress (Emilia Under) is a female Frederick the Great who believes her students' privations, including a lack of food, will forge Prussian steel and make them suitable mothers for more soldiers. The striped dresses the girls wear sinisterly augur the prison clothes worn in the Nazi concentration camps. Far from being crushed, however, they exhibit camaraderie that blooms into a rebellion against the headmistress’s draconian rule.

Mädchen in Uniform was adapted by Christa Winsloe and Friedrich Dammann from Winsloe’s autobiographical play Yesterday and Day and filmed with an all-female cast. A popular new student at the boarding school, Manuela (Hertha Thiele) develops a crush on her beautiful form mistress Fräulein von Bernburg (Dorothea Wieck) after the latter kisses her fleetingly on the lips instead of giving her the same peck on the forehead she gives Manuela's dorm mates before lights out.

Having triumphed in male attire as the romantically thwarted Don Carlos in the school production of Schiller’s play, Manuela drunkenly acts out, threatening scandal. Defiantly compassionate, Fräulein von Bernburg disobeys the headmistress's order not to speak to Manuela again, summoning her to her room to comfort her and tell her they can't speak in the future. This provokes Manuela's final crisis. A criticism levelled at the film is that Fräulein von Bernburg is not as subversive a figure as she might have been but ultimately a conformist unwilling to rock the boat.

Having triumphed in male attire as the romantically thwarted Don Carlos in the school production of Schiller’s play, Manuela drunkenly acts out, threatening scandal. Defiantly compassionate, Fräulein von Bernburg disobeys the headmistress's order not to speak to Manuela again, summoning her to her room to comfort her and tell her they can't speak in the future. This provokes Manuela's final crisis. A criticism levelled at the film is that Fräulein von Bernburg is not as subversive a figure as she might have been but ultimately a conformist unwilling to rock the boat.

The vertiginous staircase tower at the centre of the school promises a tragic climax. However, the film doesn’t end like the play and the faithful 1968 BBC dramatisation that starred Francesca Annis as Manuela and Virginia McKenna as Fräulein von Bernburg. I saw that version as a child and was shaken by its eroticism and chilling final image; even in ultra-permissive Weimar Germany, Sagan and Winsloe could only go so far on film. (The Berlin staging of the play had emphasised the lesbian theme more than the Leipzig production starring Thiele.)

The psychological rationale for Manuela’s infatuation – she grieves for her dead mother – undercuts her desire for Fräulein von Bernburg and the sense they recognize each other's sexuality instantaneously. But Mädchen in Uniform succeeded as a transgressive film that issues a storm warning about fascism.

Among the extras on the BFI’s dual-format disk, Bibi Berki’s “The Kiss: The Women Who Made a Movie Masterpiece” is a fascinating archaeological podcast on the collaboration between the film “outsiders” Winsloe (a sculptor and one-time baroness) and Sagan (a Max Reinhardt-trained stage actor, director, and producer who cared little for movies and made only two more). It extends to the appreciative British regional reviews and to Winsloe’s tragic end in France in 1944.

Last year in the US, Mädchen in Uniform was released on Blu-ray with two other German films, Carl Theodor Dreyer’s Michael (1924) and Reinhold Schünzel’s Victor and Victoria (1933), under the rubric "Pioneers of Queer Cinema". On the BFI Mädchen disc, critic Chrystel Oloukoï’s video essay "Women and Sexuality in Weimar Cinema" analyses the world of these films and the likes of the 1925 Greta Garbo vehicle The Joyless Street and the 1929 Louise Brooks pair Pandora’s Box and Diary of a Lost Girl, each directed by GW Pabst, the leading exponent of the counter-Expressionist Die Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement.

Also included are three silent films from the BFI National Archive that ratchet up the (Queer) girl power. They’re augmented by a 1940 item about a young women’s fitness group, directed by the British documentarist Mary Field, that – were it not for newsreader EVH Emmett's voiceover narration – could have been a lesbian idyll rather than a sexist exploitation film that implies women belong in the kitchen.

Add comment