Gardener Narvel (Joel Edgerton) sniffs soil the way Blue Velvet’s Frank inhaled gas, finding erasure and release. Following Ethan Hawke’s priest in First Reformed (2017) and Oscar Isaac’s titular job in The Card Counter (2021), Paul Schrader’s latest driven protagonist verges on absurd, finding solace in pruning before deploying his secateurs with a prior, particular set of skills.

Narvel is the head gardener at the plantation-style estate of aristocratic Norma Haverhill (Sigourney Weaver). He’s a middle-aged historian and philosopher of horticulture, keeping a journal at a monastic desk. “Gardening is a belief in the future,” he theorises; plan, and “change will come in due course”. With his slicked-back hair, fireplug figure and contained talk, Narvel knows how to navigate his sanctuary with arrogant, peremptory and vulnerably aging Nora. Blue jellyfish wallpaper decorates the dining room, poison tendrils dangling, where she softens and leans in coquettishly to her “sweet-pea”.

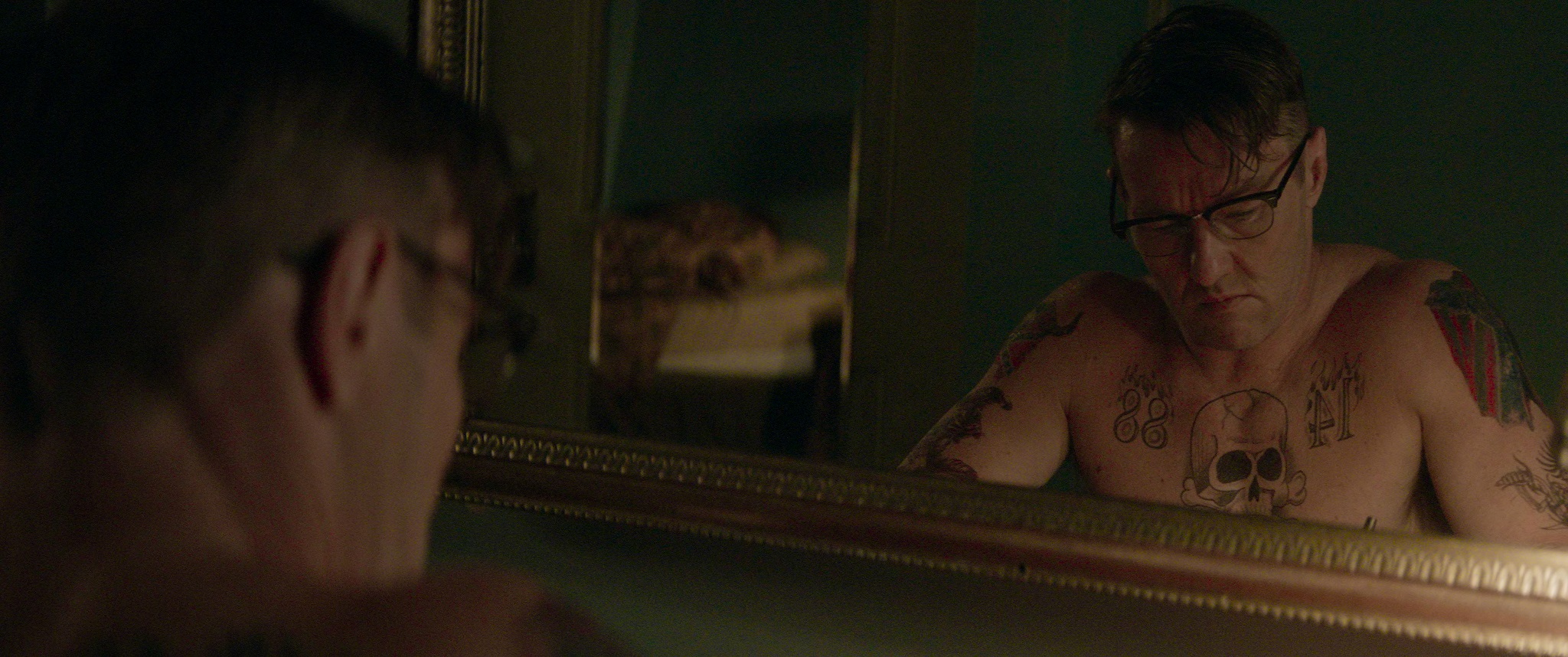

Schrader’s chill Calvinist austerity, so profoundly unlike his early collaborator Scorsese’s pumping Catholic blood, douses the garden light winter grey, while stiff conversations match Alexander Dynan’s static camera and Devonté Hynes’ cool, floating synth score. A gunshot’s orange spark heats the film, a flashback and foretelling of Narvel’s buried life as a white supremacist militia hitman. Now he’s in Witness Protection and hiding out in his manicured Eden, even his assumed name usefully close to Norma. When she invites her long lost, mixed-race great-niece Maya (Quintessa Swindell, pictured above) to be his apprentice, the young woman’s easier warmth and familiar junkie background stir what he dreamily terms “seeds of love”, scarred by the Nazi faith still tattooed on his skin.

Schrader’s chill Calvinist austerity, so profoundly unlike his early collaborator Scorsese’s pumping Catholic blood, douses the garden light winter grey, while stiff conversations match Alexander Dynan’s static camera and Devonté Hynes’ cool, floating synth score. A gunshot’s orange spark heats the film, a flashback and foretelling of Narvel’s buried life as a white supremacist militia hitman. Now he’s in Witness Protection and hiding out in his manicured Eden, even his assumed name usefully close to Norma. When she invites her long lost, mixed-race great-niece Maya (Quintessa Swindell, pictured above) to be his apprentice, the young woman’s easier warmth and familiar junkie background stir what he dreamily terms “seeds of love”, scarred by the Nazi faith still tattooed on his skin.

The outside crashes in when Maya’s old junkie boyfriend beats her. There is something schematic about what follows, especially for Schrader. Narvel is one of the director’s dirty white knights, saving a woman on his own brutal terms, like De Niro’s Travis and Jodie Foster’s Iris in Taxi Driver (1976), and George C. Scott’s avenging father in Hardcore (1979). Lynne Ramsay’s You Were Never Really Here (2017) is among the many other films attracted to this territory. Still, there’s unmistakable relief when the untethered camera prowls through the diner where Narvel meets his cop handler, and we escape into low-rise streets with their daytime dealers, and a motel at night’s sepulchral neon avenues. Though filmed in Louisiana, the only overt sense of the South is back at Norma’s subtly haunted, surely slave-era mansion.

There is a piquant perversity in Narvel’s sexual relations, submitting to older, powerful Norma then younger, black Maya, who purges her visceral loathing of his Nazi-inscribed body as he kneels naked before her. The daughter lost with his old self may be Maya’s age, and Norma’s sneer at Humbert Humbert/Lolita “obscenity” is Schrader’s acknowledgement of changing sensitivities. Narvel’s younger relationship stands anyway. So does his vigilante satisfaction, the place where Taxi Driver met Dirty Harry and Seventies liberal ire.

There is a piquant perversity in Narvel’s sexual relations, submitting to older, powerful Norma then younger, black Maya, who purges her visceral loathing of his Nazi-inscribed body as he kneels naked before her. The daughter lost with his old self may be Maya’s age, and Norma’s sneer at Humbert Humbert/Lolita “obscenity” is Schrader’s acknowledgement of changing sensitivities. Narvel’s younger relationship stands anyway. So does his vigilante satisfaction, the place where Taxi Driver met Dirty Harry and Seventies liberal ire.

Schrader has taken some wild detours in the quarter-century since James Coburn’s Affliction Oscar marked his Hollywood swansong, revving into micro-budget cul-de-sacs (2013’s Brett Easton Ellis/Lindsay Lohan erotic thriller The Canyons), strange tales (2008’s Adam Resurrected) and mainstream misfires (2014’s The Dying of the Light). Master Gardener completes what he’s called his “man in a room” trilogy. With some similarities to Mike Hodges' late, existential thrillers, they make Schrader his own subgenre, gripping in their honed riffs on his central masculine theme, but with diminishing returns here. Only his growing belief in love surprises.

Add comment