A week from now he could be the all-time Oscar king. If Daniel Day-Lewis’s performance in Lincoln wins him a third Best Actor award, it will send him clear of a thoroughbred field of nine past double-winners, Jack Nicholson, Spencer Tracy and Dustin Hoffman among them. Those other nine were all American. Uniquely for an Englishman, Day-Lewis isn’t politely respected in Hollywood for his theatrical technique, but matches the screen intensity and exhaustive Method of Brando and De Niro. Ever since his first Oscar as the cerebral palsy-afflicted Irish writer Christy Brown in My Left Foot (1989), he has vanished into roles where he’s unrecognisable, not answering to his own name till they’re done.

Born into a very different elite in 1957 – his parents were Anglo-Irish Poet Laureate Cecil Day-Lewis and actress Jill Balcon, daughter of Ealing Studios boss Sir Michael Balcon – Daniel Day-Lewis has become the actor of choice to play American giants, whether winning Oscar number two as malign oil magnate Daniel Plainview in There Will Be Blood (2007), or resurrecting a wearily human, benign Abraham Lincoln for Spielberg.

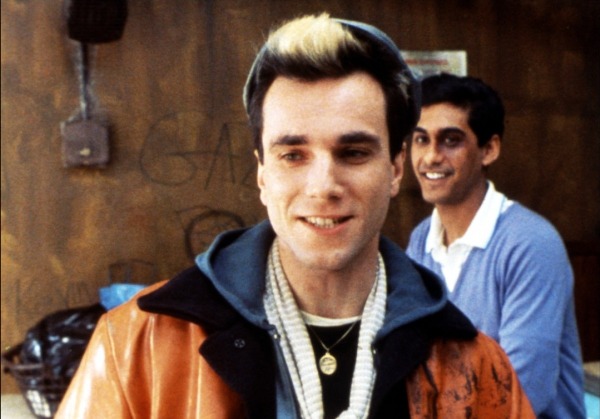

You can glimpse him on-screen as long ago as 1971, as a child hooligan in John Schlesinger’s Sunday Bloody Sunday. He tried to become an apprentice cabinet-maker before settling on his mother’s career, and a sturdy theatrical background preceded My Beautiful Launderette (1986). With its interracial, same-sex young lovers, exploded class and race stereotypes and vivid humanity, Hanif Kureishi’s screenplay pointed to daring possibilities for British cinema. Most were dashed, among them a career in his homeland for Day-Lewis. He’s said that the British “kitchen sink” films of the Sixties were “the most important film experience I had”, and he develops that tradition here as Johnny (pictured above with Gordon Warnecke), a working-class misfit with bashful virility, and the deep-voiced authority of the actor’s real, privileged London background. Merchant-Ivory’s A Room With A View, in which he played an effete aristocrat, opened on the same day in New York, giving notice of his chameleon capacities. The New York Critics Circle named him Best Supporting Actor for both. But British cinema didn’t have the room for him. In 2007, he said with regret that he couldn’t remember the last time there’d been an offer from home.

You can glimpse him on-screen as long ago as 1971, as a child hooligan in John Schlesinger’s Sunday Bloody Sunday. He tried to become an apprentice cabinet-maker before settling on his mother’s career, and a sturdy theatrical background preceded My Beautiful Launderette (1986). With its interracial, same-sex young lovers, exploded class and race stereotypes and vivid humanity, Hanif Kureishi’s screenplay pointed to daring possibilities for British cinema. Most were dashed, among them a career in his homeland for Day-Lewis. He’s said that the British “kitchen sink” films of the Sixties were “the most important film experience I had”, and he develops that tradition here as Johnny (pictured above with Gordon Warnecke), a working-class misfit with bashful virility, and the deep-voiced authority of the actor’s real, privileged London background. Merchant-Ivory’s A Room With A View, in which he played an effete aristocrat, opened on the same day in New York, giving notice of his chameleon capacities. The New York Critics Circle named him Best Supporting Actor for both. But British cinema didn’t have the room for him. In 2007, he said with regret that he couldn’t remember the last time there’d been an offer from home.

American Phil Kaufman’s film of Milan Kundera's The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1988) made him a leading man. My Left Foot’s Oscar made him a star, and began his reputation for extremes of preparation. He stayed in palsied character (pictured right), requiring set-hands to lift him in his wheelchair. Prior to his next role, as proto-Western superhero Hawkeye in Michael Mann’s The Last of the Mohicans (1992), he reputedly spent six months living and foraging in the wilderness.

American Phil Kaufman’s film of Milan Kundera's The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1988) made him a leading man. My Left Foot’s Oscar made him a star, and began his reputation for extremes of preparation. He stayed in palsied character (pictured right), requiring set-hands to lift him in his wheelchair. Prior to his next role, as proto-Western superhero Hawkeye in Michael Mann’s The Last of the Mohicans (1992), he reputedly spent six months living and foraging in the wilderness.

One of his conditions to Spielberg for playing Lincoln was a startling full year of preparation. Tired of the rumours that he was eccentric or insane, he recently explained his methods. “I take a long time because I enjoy the work and it pleases me to take time over it,” he told Time Out. “There’s huge pleasure in discovery so it’s a joyful thing, it’s a game.” He has, though, also said of acting: “I need to feel that there’s a mystery there”. The man who quit his last stage role as Hamlet in 1989 because he saw his own father’s ghost before him has an equally unfashionable attribute for an English actor: a belief in the inexplicable, and that his job is something more than smoke and mirrors.

The Last of the Mohicans was a great hit, presenting Day-Lewis at his most thrillingly heroic. It made plain the movie star charisma that he usually masks. But Scorsese’s The Age of Innocence and an Oscar-nominated reunion with My Left Foot director Jim Sheridan for In the Name of the Father, both 1993, ended his most prolific period. After 1996’s The Crucible (where, visiting its author Arthur Miller, he met the playwright’s daughter Rebecca, whom he married that year) and a less happy reunion with Sheridan, The Boxer (1997), he abandoned acting for five years. Moving to Italy with his wife and their young son, he returned to his first love of woodwork, and apprenticed as a cobbler. This was seen as another symptom of incipient madness, by those who couldn’t imagine giving up acting for such “ordinary” work. Really, it was scrupulous sanity from a man who has preserved his privacy to survive. You can’t be a “rarefied creature”, he’s said, and act. You have to be amongst people to play them. This period of retreat gave him the proven strength of not needing Hollywood. But since Scorsese came to Italy in 2002 to persuade him back to work, Hollywood has needed him.

The Last of the Mohicans was a great hit, presenting Day-Lewis at his most thrillingly heroic. It made plain the movie star charisma that he usually masks. But Scorsese’s The Age of Innocence and an Oscar-nominated reunion with My Left Foot director Jim Sheridan for In the Name of the Father, both 1993, ended his most prolific period. After 1996’s The Crucible (where, visiting its author Arthur Miller, he met the playwright’s daughter Rebecca, whom he married that year) and a less happy reunion with Sheridan, The Boxer (1997), he abandoned acting for five years. Moving to Italy with his wife and their young son, he returned to his first love of woodwork, and apprenticed as a cobbler. This was seen as another symptom of incipient madness, by those who couldn’t imagine giving up acting for such “ordinary” work. Really, it was scrupulous sanity from a man who has preserved his privacy to survive. You can’t be a “rarefied creature”, he’s said, and act. You have to be amongst people to play them. This period of retreat gave him the proven strength of not needing Hollywood. But since Scorsese came to Italy in 2002 to persuade him back to work, Hollywood has needed him.

Bill the Butcher in Scorsese’s primal 19th century gangster epic Gangs of New York (pictured above) was a role De Niro had been offered, passing a cinematic torch. Playing Eminem’s “Lose Yourself” in his trailer to work himself into a new focused ferocity, in his scenes with Leonardo DiCaprio the screen seems to tilt towards Day-Lewis, so outmatched is the younger star by a heavyweight in his prime. With his waxed moustache and brimstone malevolence, Bill is a villain from melodrama, made human.

Daniel Plainview in Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood (pictured above) is another thick-moustached, American force of nature, a pathological loner who wants to make enough money “so I can get away from everyone”, building an oil empire as he tears down his life. Day-Lewis’s single-minded commitment connects him to such loners, and he gives Plainview the volcanic vitality which simmers through all his acting. His second Oscar was inarguable.

Daniel Plainview in Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood (pictured above) is another thick-moustached, American force of nature, a pathological loner who wants to make enough money “so I can get away from everyone”, building an oil empire as he tears down his life. Day-Lewis’s single-minded commitment connects him to such loners, and he gives Plainview the volcanic vitality which simmers through all his acting. His second Oscar was inarguable.

You could build a bold, dark history of America from Day-Lewis’s work in The Last of the Mohicans, Gangs of New York, There Will Be Blood and now Lincoln. It took Spielberg 10 years to persuade him to play the country’s most beloved President. Day-Lewis typically worried whether it was right to bring Lincoln “back to life”, and from the thin Kentucky twang of his voice to his pained, forbearing folksiness, that is what his year’s research attempts. This Lincoln laughs at his own jokes, dodging the film’s sometimes inescapable knowledge that this is “history”. He is the latest landmark creation of a protean, devoted actor.

Add comment